PromptSpy ushers in the era of Android threats using GenAI

ESET researchers discover PromptSpy, the first known Android malware to abuse generative AI in its execution flow

WeLiveSecurity – Read More

ESET researchers discover PromptSpy, the first known Android malware to abuse generative AI in its execution flow

WeLiveSecurity – Read More

Welcome to this week’s edition of the Threat Source newsletter.

Generative AI and agentic AI are here to stay. Although I believe that the advantages that AI brings to bad guys may be overstated, these new technologies allow threat actors to conduct attacks at a faster rate than before.

One capability that AI improves for threat actors is the ability to reconnoitre employees, discover their interests, and craft social engineering lures specific to them. Being able to deliver tailored, targeted social engineering using the language and tone most likely to trick an individual is a useful tool for the bad guys.

However, if AI brings advantages to those who seek to attack us, we shouldn’t overlook the benefits that it brings to defenders and the new weaknesses it exposes in the bad guys. If AI agents are searching for employees who are vulnerable to social engineering; then let us serve them exactly what that are looking for.

AI tools can create a whole army of fictitious employees who can be a rich source of threat intelligence. With AI we can easily create social media profiles of fake employees to entice malicious profiling agents. These AI avatars can post social media content or upload AI generated CVs or other documents to AI systems, leaving a trail of breadcrumbs for malicious agents to discover and follow.

Clearly, any message sent to the email address of an AI-generated employee is certain to be spam. We can update our lists of potentially malicious IP addresses and URLs appropriately. Similarly, we can create accounts on messaging platforms for our fake employees and wait for the social engineering attempts to analyse and block

Any attempt to access services or log-in using the credentials of an AI employee can only be malicious. Again, defensive teams can quickly and easily block the connecting IP address to nip in the bud any malicious campaign.

Malicious use of AI doesn’t need to be thought of only as a threat. It can be a way to turn the tables on threat actors and use their own tools against them. By understanding how AI tools are profiling and collecting information about our users, we can flood these tools with disinformation and treat any resulting attacks as a rich source of threat intelligence rather than as a source of concern.

AI is changing things for both attackers and defenders. New tools and capabilities allow us to think differently about defense and how we can increasingly make life difficult for the bad guys.

In our latest Vulnerability Deep Dive, a Cisco Talos researcher discovered six vulnerabilities in the Socomec DIRIS M-70 industrial gateway by emulating just the Modbus protocol handling thread, rather than the whole system. Using tools like Unicorn Engine, AFL, and Qiling for fuzzing and debugging, this “good enough” approach made it possible to find and analyze weaknesses despite hardware protections. The vulnerabilities were responsibly disclosed and have been patched by the manufacturer.

Vulnerabilities in industrial gateways like the M-70 can cause major disruptions, especially in critical infrastructure, data centers, and health care. Attackers could exploit these flaws to stop operations or manipulate processes, leading to financial loss and equipment damage. The research highlights how even devices with strong hardware protections can still be vulnerable through their communication protocols.

Organizations using Socomec DIRIS M-70 gateways should apply the manufacturer’s patches to fix the vulnerabilities. To detect exploitation attempts, defenders should download and use the latest Snort rulesets from Snort.org, as recommended in the blog. Finally, regularly monitor industrial devices for unusual activity and review security controls around critical gateways.

CISA navigates DHS shutdown with reduced staff

CISA is currently operating at roughly 38% capacity (888 out of 2,341 staff) due to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security shutdown that began February 14, 2026. KEV is one area that remains. (SecurityWeek)

EU Parliament blocks AI tools over cyber, privacy fears

According to an internal email seen by POLITICO, EU Parliament had disabled “built-in artificial intelligence features” on corporate tablets after its IT department assessed it couldn’t guarantee the security of the tools’ data. (POLITICO)

Supply chain attack embeds malware in Android devices

Researchers have spotted new malware embedded in the firmware of Android devices from multiple vendors that injects itself into every app on infected systems, giving attackers virtually unrestricted remote access to them. (Dark Reading)

Data breach at fintech giant Figure affects close to a million customers

Troy Hunt, security researcher and creator of the site Have I Been Pwned, analyzed the data allegedly taken from Figure and found it contained 967,200 unique email addresses associated with Figure customers. (TechCrunch)

Amnesty International: Intellexa’s Predator spyware used to hack iPhone of journalist in Angola

Government customers of commercial surveillance vendors are increasingly using spyware to target journalists, politicians, and other ordinary citizens, including critics. (TechCrunch)

New threat actor, UAT-9921, leverages VoidLink framework in campaigns

Cisco Talos recently discovered a new threat actor, UAT-9221, leveraging VoidLink in campaigns. Their activities may go as far back as 2019, even without VoidLink.

Humans of Talos: Ryan Liles, master of technical diplomacy

Amy chats with Ryan Liles, who bridges the gap between Cisco’s product teams and the third-party testing labs that put Cisco products through their paces. Hear how speaking up has helped him reshape industry standards and create strong relationships in the field.

Talos Takes: Ransomware chills and phishing heats up

Amy is joined by Dave Liebenberg, Strategic Analysis Team Lead, to break down Talos IR’s Q4 trends. What separates organizations that successfully fend off ransomware from those that don’t? What were the top threats facing organizations? Can we (pretty please) get a sneak peek into the 2025 Year in Review?

SHA256: 9f1f11a708d393e0a4109ae189bc64f1f3e312653dcf317a2bd406f18ffcc507

MD5: 2915b3f8b703eb744fc54c81f4a9c67f

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=9f1f11a708d393e0a4109ae189bc64f1f3e312653dcf317a2bd406f18ffcc507

Example Filename: https_2915b3f8b703eb744fc54c81f4a9c67f.exe

Detection Name: Win.Worm.Coinminer::1201

SHA256: 41f14d86bcaf8e949160ee2731802523e0c76fea87adf00ee7fe9567c3cec610

MD5: 85bbddc502f7b10871621fd460243fbc

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=41f14d86bcaf8e949160ee2731802523e0c76fea87adf00ee7fe9567c3cec610

Example Filename: 85bbddc502f7b10871621fd460243fbc.exe

Detection Name: W32.41F14D86BC-100.SBX.TG

SHA256: 90b1456cdbe6bc2779ea0b4736ed9a998a71ae37390331b6ba87e389a49d3d59

MD5: c2efb2dcacba6d3ccc175b6ce1b7ed0a

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=90b1456cdbe6bc2779ea0b4736ed9a998a71ae37390331b6ba87e389a49d3d59

Example Filename:d4aa3e7010220ad1b458fac17039c274_64_Dll.dll

Detection Name: Auto.90B145.282358.in02

SHA256: 96fa6a7714670823c83099ea01d24d6d3ae8fef027f01a4ddac14f123b1c9974

MD5: aac3165ece2959f39ff98334618d10d9

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=96fa6a7714670823c83099ea01d24d6d3ae8fef027f01a4ddac14f123b1c9974

Example Filename: d4aa3e7010220ad1b458fac17039c274_63_Exe.exe

Detection Name: W32.Injector:Gen.21ie.1201

SHA256: 38d053135ddceaef0abb8296f3b0bf6114b25e10e6fa1bb8050aeecec4ba8f55

MD5: 41444d7018601b599beac0c60ed1bf83

Talos Rep: https://talosintelligence.com/talos_file_reputation?s=38d053135ddceaef0abb8296f3b0bf6114b25e10e6fa1bb8050aeecec4ba8f55

Example Filename: content.js

Detection Name: W32.38D053135D-95.SBX.TG

Cisco Talos Blog – Read More

Cyble Research & Intelligence Labs (CRIL) tracked 1,158 vulnerabilities last week. Of these, 251 vulnerabilities already have publicly available Proof-of-Concept (PoC) exploits, significantly increasing the likelihood of real-world attacks.

A total of 94 vulnerabilities were rated critical under CVSS v3.1, while 43 were rated critical under CVSS v4.0.

In parallel, CISA issued 15 ICS advisories covering 87 vulnerabilities affecting industrial environments. These vulnerabilities impacted vendors including Siemens, Yokogawa, AVEVA, Hitachi Energy, ZLAN, ZOLL, and Airleader.

Additionally, 8 vulnerabilities were added to CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog, reflecting confirmed exploitation in the wild.

CVE-2025-40554 — SolarWinds Web Help Desk (Critical)

CVE-2025-40554 is a critical authentication bypass vulnerability affecting SolarWinds Web Help Desk versions prior to 2026.1. The flaw allows unauthenticated remote attackers to invoke privileged functionality without valid credentials, potentially leading to full compromise of helpdesk systems.

Cyble observed this vulnerability being discussed on underground forums shortly after disclosure, and a public PoC is available. The vulnerability’s presence in enterprise environments increases the risk of initial access and lateral movement.

CVE-2026-1340 — Ivanti Endpoint Manager Mobile (Critical)

CVE-2026-1340 is a critical code injection vulnerability in Ivanti Endpoint Manager Mobile (EPMM). A remote, unauthenticated attacker can exploit the flaw to achieve arbitrary remote code execution without user interaction.

The vulnerability has been captured in dark web discussions and has a publicly available PoC , significantly lowering the barrier to exploitation.

CVE-2026-21509 — Microsoft Office (High Severity, Actively Exploited)

CVE-2026-21509 is a feature-bypass vulnerability in Microsoft Office that allows crafted documents to circumvent built-in security protections. Attackers can deliver malicious Office files that execute payloads once opened by the victim.

The flaw has been actively exploited by threat actors including APT28 and RomCom , highlighting its operational impact.

CVE-2026-1529 — Keycloak (High Impact)

CVE-2026-1529 affects Red Hat’s Keycloak and involves improper validation of JWT invitation token signatures. Attackers can manipulate trusted token contents to gain unauthorized access to organizational resources.

A PoC is available, and the vulnerability surfaced on underground forums shortly after disclosure.

CVE-2026-23906 — Apache Druid (Critical)

CVE-2026-23906 is a critical authentication bypass vulnerability in Apache Druid, enabling unauthorized access to sensitive data stores.

CVE-2026-0488 — SAP CRM & SAP S/4HANA (Critical)

CVE-2026-0488 is a critical code injection vulnerability affecting SAP CRM and SAP S/4HANA. An authenticated attacker can exploit improper function module calls to execute arbitrary SQL statements, potentially resulting in full database compromise.

CISA added 8 vulnerabilities to the KEV catalog during the reporting period. The most important of these were:

KEV additions reflect confirmed exploitation in the wild and often signal heightened ransomware or espionage activity.

CISA issued 15 ICS advisories covering 87 vulnerabilities, with the majority rated high severity.

CVE-2026-25084 & CVE-2026-24789 — ZLAN5143D (Critical)

These critical vulnerabilities in ZLAN Information Technology Co.’s ZLAN5143D device involve missing authentication for critical functions.

Successful exploitation could allow attackers to bypass authentication controls or reset device passwords, potentially enabling unauthorized configuration changes and interference with industrial communications. Researchers also identified internet-facing instances, increasing exposure risk.

CVE-2025-52533 — Siemens SINEC OS (Critical)

CVE-2025-52533 is a critical out-of-bounds write vulnerability in Siemens SINEC OS before version 3.3, potentially enabling memory corruption and system compromise in industrial network environments.

CVE-2026-1358 — Airleader Master (Critical)

CVE-2026-1358 is a critical, unrestricted file-upload vulnerability in Airleader Master systems. Successful exploitation could allow attackers to upload malicious files, potentially resulting in remote code execution in OT environments.

Analysis of the ICS advisories shows that Critical Manufacturing and Energy sectors appear in 98.9% of reported vulnerabilities, showcasing concentrated exposure in these environments.

The cross-sector nature of these vulnerabilities underscores the interdependencies between Energy, Manufacturing, Transportation, Water, and Food systems.

The convergence of high-volume IT vulnerabilities and significant ICS exposure highlights the continued expansion of the attack surface across enterprise and industrial environments. With over 250 PoCs publicly available and multiple KEV additions confirming active exploitation, organizations must prioritize rapid remediation and risk-based vulnerability management.

Security best practices include:

Cyble’s comprehensive attack surface management solutions help organizations continuously monitor internal and external assets, prioritize remediation, and detect early warning signals of exploitation. Additionally, Cyble’s threat intelligence and third-party risk intelligence capabilities provide visibility into vulnerabilities actively discussed in underground communities, enabling proactive defense against both IT and ICS threats.

The post The Week in Vulnerabilities: SolarWinds, Ivanti, and Critical ICS Exposure appeared first on Cyble.

Cyble – Read More

G2, the world’s largest and most trusted software marketplace, has recognized ANY.RUN among the Best Software Companies.

The ranking is based on verified reviews from organizations actively using ANY.RUN’s solutions. It reflects the company’s strong international presence and measurable impact across global cybersecurity markets.

Recognition on G2’s Top 50 Best Software Companies list is a reflection of peer validation, powered by customer reviews and feedback. We are very grateful to all analysts, SOC teams, and experts whose insights and evaluations contributed to the ranking.

For ANY.RUN, entering the G2 ranking is a milestone, not a finish line. We will continue to invest in product innovation, community-driven improvements, and measurable outcomes for security operations worldwide.

ANY.RUN delivers measurable operational value to security teams with demanding workloads and strict SLAs. Among results reported by our customers are 50%+ reduction in investigation & IOC extraction time and 30–55% fewer irrelevant escalations.

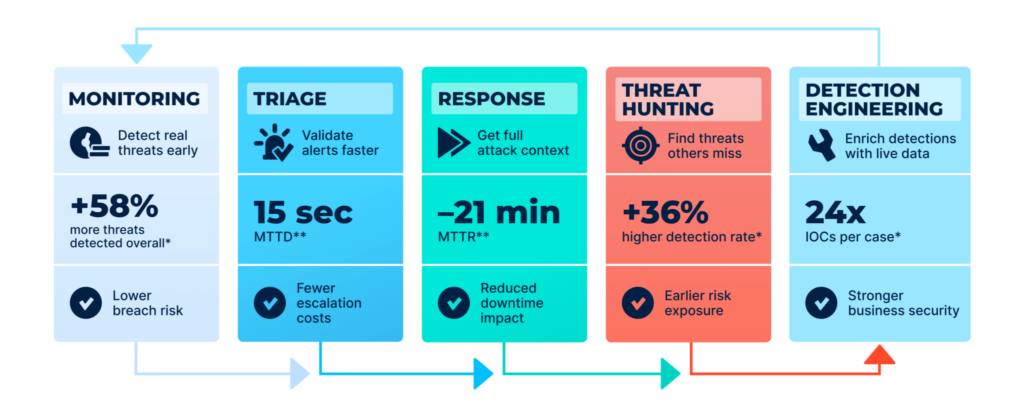

Beyond the metrics, ANY.RUN’s rising position in software rankings is by its ability to solve operational challenges across the SOC lifecycle:

We support analysts in accelerating investigations, reducing risk, and improving operational outcomes across industries. Among 15,000 SOC teams applying our solutions, there are 3,102 IT & technology companies, 1,778 financial institutions, 1,059 government entities, and 919 healthcare providers.

ANY.RUN is used broadly by organizations with high security requirements, including the world’s largest enterprises:

“We just stopped losing time to uncertainty. Now we can confirm what’s happening faster and escalate only when it actually makes sense.”

Fortune 500 technology company on embedding ANY.RUN to their workflow.

ANY.RUN has become an integral component of modern security operations, enabling teams to make faster, more confident decisions across Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3. It integrates seamlessly into existing workflows and reinforces the full investigation lifecycle from initial validation to in-depth analysis and continuous threat monitoring.

By exposing real attacker behavior, enriching investigations with critical context, and ensuring detections reflect the evolving threat landscape, ANY.RUN helps SOC teams reduce alert fatigue, accelerate response times, and minimize operational impact.

Today, more than 600,000 security professionals and 15,000 organizations worldwide rely on ANY.RUN to streamline triage, reduce unnecessary escalations, and stay ahead of constantly shifting phishing and malware campaigns.

The post G2 Recognizes ANY.RUN Among the Top 50 Best Software Companies in the Region appeared first on ANY.RUN’s Cybersecurity Blog.

ANY.RUN’s Cybersecurity Blog – Read More

By Beenu Arora, Co-Founder and CEO, Cyble

I believe we’re witnessing the most significant event India has ever experienced. The nation stands at the cusp of a major global shift, and I want to share why I’m so bullish about India’s role in the AI revolution—and the critical security challenges we must address together.

No country will prosper without making significant changes in their AI capabilities. India is uniquely positioned to lead this transformation. We’ve already pioneered the entire FinTech ecosystem, processing payments for more than half a billion people globally. This foundation puts India at the perfect intersection of technological capability and market opportunity to ride the AI wave.

At the same time, scale brings responsibility. As AI becomes embedded across financial systems, digital public infrastructure, enterprise workflows, and citizen services, the attack surface expands alongside innovation. If India is to lead the AI revolution, we must lead in securing it as well.

At Cyble, we’re incredibly excited to invest and continue growing our AI capabilities from India—from infrastructure to applications to talent. We’re not just talking about supplying talent to the world; we’re building core infrastructure, services, and capabilities right here. That’s why we’ve invested millions of dollars and will continue doing so. India’s potential extends far beyond being a service provider—we’re becoming a global AI powerhouse.

As we build, I am also conscious that AI is not just another infrastructure layer. It is increasingly a cognitive system — capable of reasoning, contextual learning, and autonomous decision-making. That means it must be secured differently. Protecting AI systems requires thinking beyond traditional perimeter defenses and anticipating new risk categories such as model manipulation, data poisoning, prompt injection, AI-assisted reconnaissance, and sensitive data leakage.

But let me be candid about the challenge ahead. AI has fundamentally changed the game—it’s a massive structural shift. The threat landscape has evolved dramatically:

What once took hours to execute—a basic phishing attack—now happens at scale with high contextual accuracy and perfect timing.

AI agents continuously monitor user activities on LinkedIn and social media, knowing exactly who you are, what interests you, and who you communicate with.

We’re seeing over 100,000 deepfake videos being created. With apps like Grok, anyone can generate a convincing deepfake in just 60 seconds.

I’ve seen this shift firsthand.

Three years ago, a member of my leadership team received a WhatsApp call that convincingly mimicked my voice and requested a financial transaction. It was a deepfake attempt. We identified it only after careful scrutiny.

At the time, such attacks were considered sophisticated and relatively rare.

Recently, my eight-year-old son wrote a simple program that deepfaked my own mother.

The point is not novelty. It is accessibility.

What once required specialized expertise and resources is now democratized. Consumer-grade AI systems can generate convincing synthetic audio with minimal effort. The barrier to entry has collapsed. Cybercrime is being industrialized.

Phishing has entered a new era as well. For decades, phishing attempts were often detectable through poor grammar, awkward phrasing, or generic messaging. That signal has largely disappeared. AI-driven agents now scrape publicly available information, analyze behavioral patterns, and craft highly personalized messages tailored to specific individuals and roles. These agents continuously learn, retain context, and refine their attacks. Precision has replaced volume as the dominant strategy.

AI is already democratized. Bad actors have access to the same technologies as defenders. This fight will be relentless. I believe attackers will initially gain the upper hand because AI systems weren’t designed with security in mind from the beginning.

Consider this: $4.6 trillion has been invested in building AI infrastructure, applications, and toolkits. Security, as always, is catching up.

Beyond social engineering, AI is influencing technical intrusion methods as well. AI systems are increasingly capable of identifying and chaining vulnerabilities across systems, discovering weaknesses with notable efficiency. In controlled environments, AI-assisted approaches have demonstrated the ability to map exploit pathways faster than traditional methods. This compresses the time between vulnerability discovery and exploitation, shrinking defensive response windows and amplifying attacker efficiency.

AI is not simply another tool in the attacker’s arsenal. It is a multiplier.

And while organizations rapidly integrate AI into customer experiences, analytics platforms, and internal decision-making systems, security investments do not always scale proportionately.

AI is often treated as infrastructure rather than as a cognitive system requiring dedicated protection mechanisms. This creates exposure across model integrity, training data pipelines, inference layers, and external integrations.

The enterprise attack surface is expanding — and becoming more intelligent.

Despite these challenges, I’m optimistic. As defenders gain access to the right governance frameworks and infrastructure, we’ll be positioned to make these systems better and safer for everyone. This is exactly why Cyble exists—to bridge that gap and protect organizations in this new AI-driven world.

Defending against AI-driven threats requires more than traditional controls. It requires continuous external threat intelligence, early detection of impersonation campaigns, dark web visibility into emerging AI-enabled tactics, proactive attack surface management, and context-aware anomaly detection.

The race is on, and India is ready to lead not just in AI innovation but in AI security. The question isn’t whether we’ll rise to this challenge—it’s how quickly we can mobilize our talent, infrastructure, and innovation to secure the AI future.

About the Author

Beenu Arora is the Co-Founder and CEO of Cyble, a leading AI-powered threat intelligence company investing heavily in India’s cybersecurity and AI infrastructure.

The post India’s AI Revolution: Why This Is India’s Most Significant Moment appeared first on Cyble.

Cyble – Read More

We’ve written time and again about phishing schemes where attackers exploit various legitimate servers to deliver emails. If they manage to hijack someone’s SharePoint server, they’ll use that; if not, they’ll settle for sending notifications through a free service like GetShared. However, Google’s vast ecosystem of services holds a special place in the hearts of scammers, and this time Google Tasks is the star of the show. As per usual, the main goal of this trick is to bypass email filters by piggybacking the rock-solid reputation of the middleman being exploited.

The recipient gets a legitimate notification from an @google.com address with the message: “You have a new task”. Essentially, the attackers are trying to give the victim the impression that the company has started using Google’s task tracker, and as a result they need to immediately follow a link to fill out an employee verification form.

To deprive the recipient of any time to actually think about whether this is necessary, the task usually includes a tight deadline and is marked with high priority. Upon clicking the link within the task, the victim is presented with an URL leading to a form where they must enter their corporate credentials to “confirm their employee status”. These credentials, of course, are the ultimate goal of the phishing attack.

Of course, employees should be warned about the existence of this scheme — for instance, by sharing a link to our collection of posts on the red flags of phishing. But in reality, the issue isn’t with any one specific service — it’s about the overall cybersecurity culture within a company. Workflow processes need to be clearly defined so that every employee understands which tools the company actually uses and which it doesn’t. It might make sense to maintain a public corporate document listing authorized services and the people or departments responsible for them. This gives employees a way to verify if that invitation, task, or notification is the real deal. Additionally, it never hurts to remind everyone that corporate credentials should only be entered on internal corporate resources. To automate the training process and keep your team up to speed on modern cyberthreats, you can use a dedicated tool like the Kaspersky Automated Security Awareness Platform.

Beyond that, as usual, we recommend minimizing the number of potentially dangerous emails hitting employee inboxes by using a specialized mail gateway security solution. It’s also vital to equip all web-connected workstations with security software. Even if an attacker manages to trick an employee, the security product will block the attempt to visit the phishing site — preventing corporate credentials from leaking in the first place.

Kaspersky official blog – Read More

Every security alert represents a decision point. Act too slowly, and a threat becomes a breach. Act without context, and analysts drown in noise. At the center of both failure modes is a single, often underestimated process: alert enrichment.

Alert enrichment is the practice of layering contextual intelligence onto raw security alerts (IP reputation, domain history, file behavior, attacker TTPs) so that analysts can make fast, accurate decisions. It sounds operational. But its downstream effects are deeply strategic: mean time to respond, analyst capacity, false-positive rates, and ultimately, whether the security function is perceived as a cost center or a competitive asset.

For the business, the difference is simple: enriched alerts lead to faster containment and fewer incidents. Poorly enriched alerts lead to delays, escalations, and avoidable losses.

Alert enrichment sits at the crossroads of detection, analysis, and response. It connects telemetry from SIEM, EDR, email security, and network controls with external and internal context such as indicators, attacker behavior, infrastructure, and historical activity.

When enrichment works well:

Considering business objectives, effective enrichment directly affects:

In short, alert enrichment defines how efficiently security investments translate into risk reduction.

Leadership increasingly demands that security spend be justified in operational terms. Alert enrichment is one of the most concrete levers available. It is measurable, improvable, and its effects cascade through the entire security operation. Organizations that treat it as a background task, rather than a core process deserving investment and optimization, consistently underperform on every metric that matters.

Many SOCs struggle because enrichment is:

The business consequences of poor enrichment practices compound over time. The most direct impact is an extended breach window. Organizations with slow enrichment workflows consistently show longer dwell times before threat detection and containment.

Beyond breach economics, there are workforce consequences. Analyst teams experiencing enrichment bottlenecks burn out faster, make more errors under time pressure, and escalate inappropriately.

Finally, poor enrichment undermines executive reporting. When MTTR and false positive rates are poor, security teams struggle to demonstrate value to the board. This erodes confidence in the function and creates pressure for headcount reductions at precisely the moment when operational capacity is already strained.

The path from dysfunctional enrichment to a streamlined, high-performance process runs through threat intelligence. High-performing SOCs enrich alerts with two types of validation:

ANY.RUN offers two distinct but deeply complementary capabilities that, together, cover the full spectrum of SOC enrichment needs: the Interactive Sandbox for live behavioral analysis of unknown threats, and Threat Intelligence Lookup for instant, structured context on known indicators.

Understanding each one, and how they interconnect, is key to applying them effectively across SOC tiers. With intelligence-backed and behavior-validated enrichment:

The SOC shifts from reactive investigation to structured decision-making.

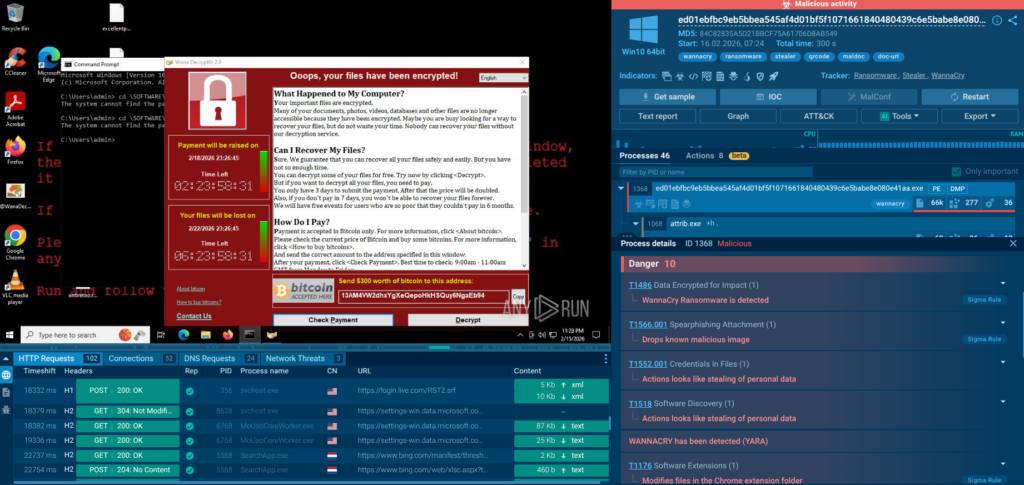

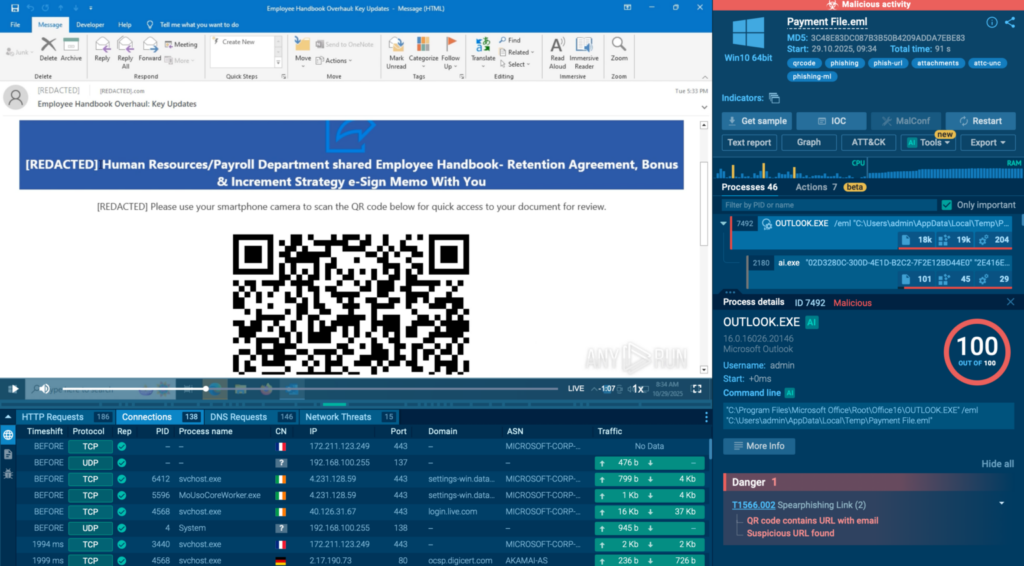

The ANY.RUN Interactive Sandbox is a cloud-based malware analysis environment that executes suspicious files and URLs and captures every aspect of their behavior in real time. It allows analysts to interact with the execution clicking through installer dialogs, entering credentials on a phishing page, following multi-stage execution chains.

Check a real-world case inside sandbox

In this sample, a QR code hidden in a phishing email leads to a CAPTCHA-protected page and then to a fake Microsoft 365 login designed to steal credentials. The sandbox detonates the full chain, reveals the phishing infrastructure, and confirms credential theft behavior in seconds.

A sandbox session generates a rich analytical output that invests in alert enrichment and aligns with business objectives:

When one analyst runs a new sample, the resulting data immediately becomes available to the entire community and feeds directly into TI Lookup’s dataset.

The Interactive Sandbox is accessible via API, allowing orchestration platforms to trigger sandbox submissions automatically when incoming files or URLs meet defined criteria and to attach the resulting behavioral analysis directly to the incident ticket.

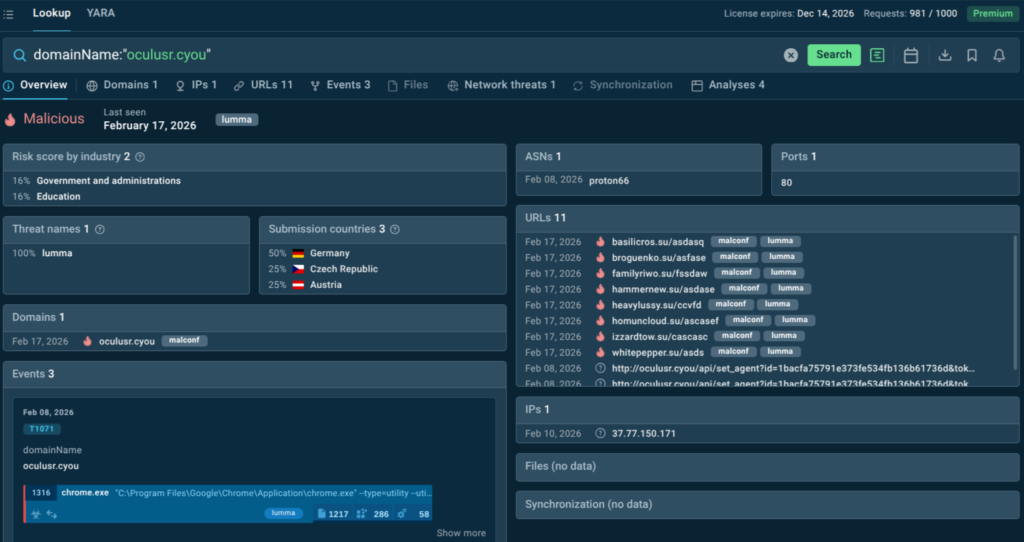

Threat Intelligence Lookup is a search-driven intelligence platform built specifically to support the investigative and enrichment needs of SOC analysts. It centralizes structured, current intelligence in a single queryable interface.

The platform aggregates data from ANY.RUN’s Sandbox. Analysts can query by over 40 parameters including IP address, domain, URL, file hash, YARA rule, or MITRE ATT&CK technique and receive structured, actionable results in seconds.

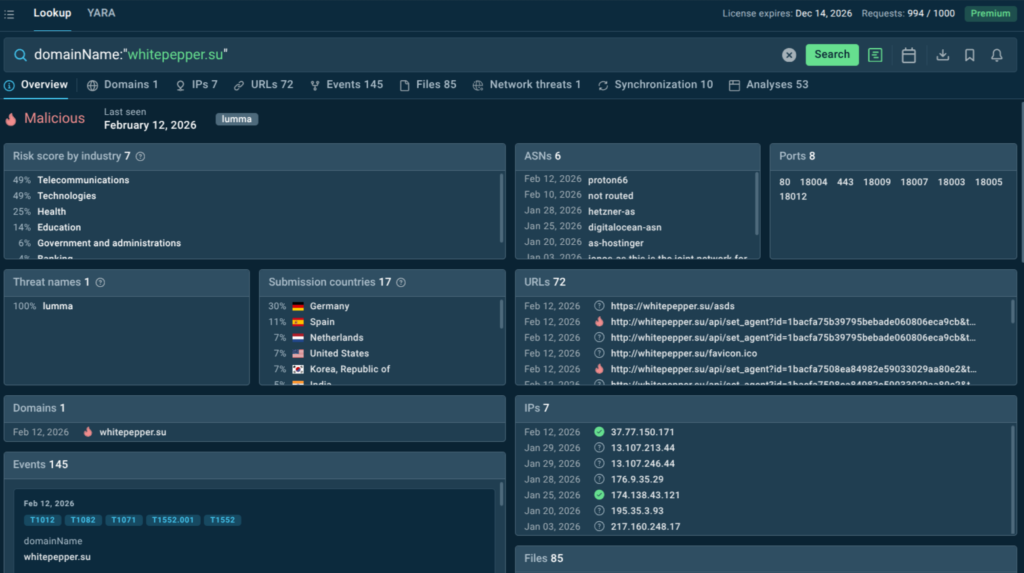

Here we can see an actionable verdict on a domain that triggered alerts: it’s malicious, associated with Lumma stealer, spotted in the very recent attacks that mostly target telecom, IT, and healthcare sectors across Europe.

TI Lookup answers the question: have we (or has anyone in the security community) seen this indicator before, and what do we know about it? The Interactive Sandbox answers the question: what does this artifact do when it runs, right now, in a real environment?

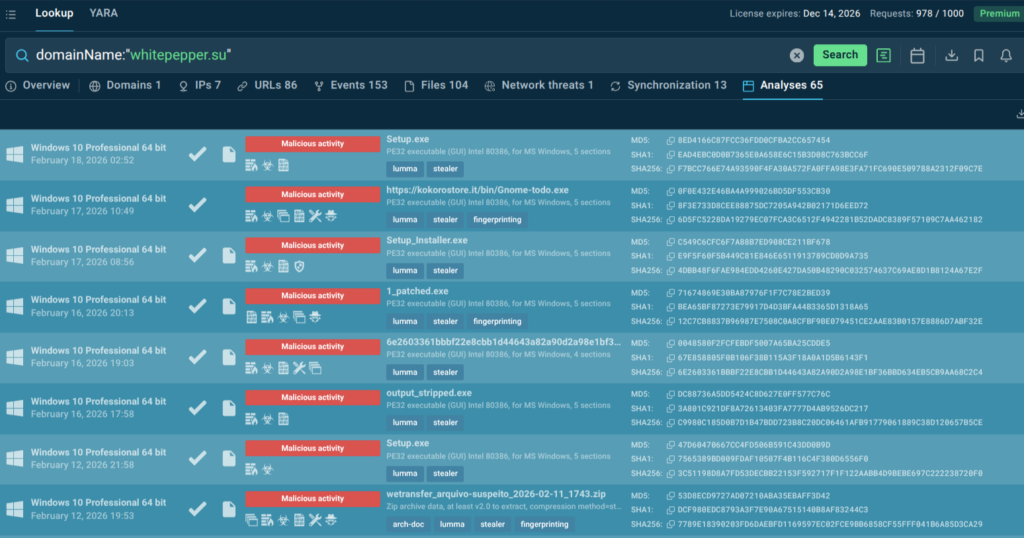

Just switch to the “Analyses” tab in TI Lookup results to see a selection of fresh malware samples featuring the artifact in question and to view analyses for full attack chains, IOCs and TTPs.

Both capabilities are designed for operational integration. TI Lookup is accessible via a web interface for direct analyst use and via API for integration into SIEM, SOAR, and ticketing platforms, enabling automated pre-enrichment of alerts before they reach a human reviewer.

Alert enrichment is not an isolated activity that affects only the analyst who performs it. It sits at the center of the SOC’s operational cycle, and its efficiency (or inefficiency) propagates through every tier and every metric. When enrichment is slow, fragmented, or dependent on stale intelligence, every downstream process suffers: triage is less accurate, investigation takes longer, containment is slower, and leadership receives metrics that tell a story of organizational underperformance.

By integrating TI Lookup and the Interactive Sandbox into the enrichment workflow, organizations address the root cause of this underperformance. Together, these capabilities cover the full surface area of enrichment need: instant structured context for known indicators, and live behavioral evidence for the unknown. The former get handled at speed, and the latter are exposed in depth. Neither replaces a professional’s judgment: both elevate it while being integrated into the analyst’s existing workflows.

When enrichment velocity increases, the key metrics that define SOC value to the business improve in tandem: MTTD drops because contextual data enables faster threat recognition; MTTR drops because analysts spend less time on data collection and more time on decision-making; false positive rates fall because richer context enables more accurate triage; and analyst capacity increases because the same team can handle greater alert volume without compromising quality.

Alert enrichment defines whether a SOC operates reactively or strategically. When alerts are supported by real attack intelligence and validated through dynamic analysis, analysts stop guessing and start deciding.

ANY.RUN’s Threat Intelligence Lookup and Interactive Sandbox together provide both precedent and proof. And when enrichment is grounded in both, security becomes faster, clearer, and more aligned with business objectives.

ANY.RUN is part of modern SOC workflows, integrating easily into existing processes and strengthening the entire operational cycle across Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3.

It supports every stage of investigation, from exposing real behavior during safe detonation, to enriching analysis with broader threat context, and delivering continuous intelligence that helps teams move faster and make confident decisions.

Today, more than 600,000 security professionals and 15,000 organizations rely on ANY.RUN to accelerate triage, reduce unnecessary escalations, and stay ahead of evolving phishing and malware campaigns.

To stay informed about newly discovered threats and real-world attack analysis, follow ANY.RUN’s team on LinkedIn and X, where weekly updates highlight the latest research, detections, and investigation insights.

Alert enrichment is the process of adding contextual and behavioral information to security alerts to enable accurate prioritization and faster response.

Because it affects response time, escalation rates, analyst workload, and ultimately the cost and impact of security incidents.

It provides real-world attack context, linking indicators to malware families, techniques, and infrastructure observed in live campaigns.

It allows analysts to safely detonate suspicious artifacts and observe real-time execution behavior, reducing uncertainty and guesswork.

Lookup provides historical evidence. Sandbox provides live behavioral proof. Together, they reduce false positives, accelerate investigations, and improve SOC-wide efficiency.

The post One Process, Every Metric: How Better Alert Enrichment Transforms SOC Performance appeared first on ANY.RUN’s Cybersecurity Blog.

ANY.RUN’s Cybersecurity Blog – Read More

This blog describes efforts at emulating functionality of the Socomec DIRIS M-70 gateway to discover vulnerabilities. In vulnerability research, knowing which tool to use for the job at hand is crucial. This post will highlight multiple emulation tools and approaches used, detail the benefits and drawbacks of each, and reveal how a “good enough” approach can really pay off.

The M-70 gateway facilitates data communication over both RS485 and Ethernet networks, supporting a wide array of industrial communication protocols, including Modbus RTU, Modbus TCP, BACnet IP, and SNMP (v1, v2, and v3). This gateway is vital for energy management in sectors like critical infrastructure, data centers, healthcare, and the general energy sector. However, as an industrial Internet-of-Things (IIoT) device, vulnerabilities in the M-70 or similar gateways can lead to severe consequences, including operational disruption, financial losses, and manipulation of industrial processes. These risks are severe, especially in critical infrastructure where a compromised gateway could lead to widespread outages or equipment damage.

This large attack surface, the impact of vulnerabilities, and the fact that the M-70 gateway runs the real-time operating system (RTOS) µC/OS-III, made it an attractive research target. There was an expectation that prior familiarity with this RTOS, gained through previous work, would offer an advantage in understanding the device’s intricacies.

Having insight into the system is critical to performing root cause analysis of any discovered vulnerabilities. Ideally, one would have real hardware and the ability to debug the software running on that hardware. The presence of an unpopulated JTAG header on the board was an exciting initial find.

However, the presence of a JTAG header does not always guarantee debug access. There are a variety of reasons for this, but in the case of the M-70 gateway, code read-out protection (RDP) Level 1 is enabled. This is a feature of STM32 microcontrollers, which provides flash memory protection. There are three possible levels (0 – 2) of this protection. Level 1 prevents flash memory reads while debugger access is detected (e.g., JTAG). When attached via JTAG, no access to Flash memory is permitted, essentially preventing debugging of the running software. The intention behind this protection is to prevent third parties (like myself) from dumping the contents of flash via JTAG.

This was bad news. It was not possible to step through the code processing malicious network messages to determine the cause of device disruption. The address for the $pc register (see Figure 2) indicates that the MCU has entered a core lock-up state.

In this project, two significant opportunities arose regarding code and memory access. First, an unencrypted firmware update file was available, providing the code that would be written to flash and eliminating the need to read it directly from memory. The second is that the ability to access SRAM while a debugger is attached is allowed with RDP Level 1 enabled (see Figure 2). This made it feasible to dump the contents of SRAM during the device’s execution and capture a snapshot of dynamic data.

While it was not possible to have fine-grained control over the processor’s state when dumping the SRAM contents, some influence could be exerted (e.g., opening a TCP connection with the device before dumping the SRAM contents). The objects and data created as a result of this connection would be present when the CPU was halted for the SRAM dump.

Emulation is one solution to this inability to debug the software natively. If the processing code of interest can be emulated, it is possible to gain visibility into the effects of a malicious message on the state of the M-70. When emulating software, it’simportant to recognize that the emulated code might not behave exactly like it would on the physical device. Full system emulation aims to mitigate this by mimicking device behavior as closely as possible, but it requires deep knowledge of system internals and significant development to accurately emulate peripherals. The focus for this project was on vulnerabilities within the Modbus protocol handling code, which ran in a single thread of the M-70 application. Rather than spending the time required for full system emulation, the decision was made to emulate only the Modbus thread. Admittedly, emulating this single thread would not be true to the device’s real-world operation. However, this deliberate time trade-off was made with the hope that it would still be “good enough” to find vulnerabilities in the Modbus protocol handling code.

The first step in this process involved utilizing the Unicorn Engine, a powerful CPU emulation framework supporting various architectures. It provided the core capability to run the Modbus thread’s code in a controlled software environment where I could then inspect the system state when processing network data.

The emulator was implemented with an entry point in the Modbus processing thread, positioned after network data had been received. Before emulating this code, the argument registers $r2 and $r3 which originally contained a pointer to network data and its length were modified to reference data originating from the emulator, along with it’s corresponding length. Once the argument registers were updated, emulation could begin and continue until that thread returned from the message processing function.

Manual inspection of network processing code is sometimes sufficient; however, this Modbus thread supports over 700 unique message types, defined by supported register values and something referred to as service identifier. The combination of these two values within a Modbus message influenced the code path of data processing, and with so many code paths to investigate, automation was clearly necessary.

Unicorn’s AFL integration made it simple to fuzz using the emulator, automatically exploring these many execution paths. AFL uses coverage-guided test case generation to maximize the number of different code paths explored. This is tool provided precisely the type of automation that was necessary. It was simple integrating AFL fuzzing into the Unicorn script, requiring only the addition of the place_input_callback function and a call to unicorn_afl_fuzz (see Figure 5).

With fuzzing came crashes, and the next step was to triage those crashes to perform root cause analysis. Typically, a debugger would be the go-to tool for this job; however, because execution was performed through emulation, GDB didn’t “just work” out of the box. A tool compatible with the Unicorn framework’s internal CPU representation was required. Conveniently, a tool called udbserver does exactly that. Udbserver is a plugin for the Unicorn engine that enables debugging of Unicorn emulated code within GDB. This tool worked as advertised and allowed remote GDB connections to the emulated code. There is only one line required to add udbserver support to a unicorn emulator: udbserver.udbserver(mu,1234,0x80fede0)beforecalling emu_start.

Observing code coverage visually is another important part of any fuzzing campaign. It helps identify unexplored paths and provides insights for root cause analysis by comparing coverage between test cases. The need for this feature prompted an investigation into the Qiling framework. Described as a full system emulator, it also supports debugging and code coverage output. Could Qiling to emulate only a single thread rather than the whole system? It would be wonderful to benefit from its features without having to spend the time to implement full system emulation.

The Qiling framework is based on Unicorn, so it was likely that the Unicorn script could be easily ported to Qiling. Figure 6 shows the API changes between unicorn engine and the Qiling framework.

It wasn’t clear from existing examples in the Qiling codebase if single thread emulation was possible. After some investigation and some small modifications to two components called the blob loader and the blob OS it became feasible to emulate just this single thread rather than the whole system. Those code changes have been integrated into the development branch of Qiling on GitHub. Also, a little bit of monkey patching was also required for my emulation script in order to output the coverage data in the correct way so that it contains accurate metadata for use in visualization tools like bncov or Lighthouse. You can see an example of this in action in the Qiling repository.

This code coverage feature turned out to be more useful than originally expected. Code coverage data from multiple test inputs was compared to identify points at which their execution paths diverged. This approach facilitated rapid identification of the root causes of the crashes generated by AFL.

This fuzzing campaign led to the discovery of multiple Modbus messages that would cause a denial of service within the device and resulted in six CVEs. You can read those vulnerability reports here: TALOS-2025-2248 (CVE-2025-54848 – CVE-2025-54851), TALOS-2025-2251 (CVE-2025-55221, CVE-2025-55222).

All the discussed vulnerabilities have been reported to the manufacturers in accordance with Cisco’s Coordinated Disclosure Policy. Each of these vulnerabilities in the affected products has been patched by the corresponding manufacturer.

For SNORT® coverage that can detect the exploitation of these vulnerabilities, download the latest rulesets from Snort.org.

In the future, Qiling will be my go-to for from the start of an emulation project. The high-level features of debugging and code coverage really make this a stand-out tool. However, if all you need is the ability to debug your scripts, udbserver is an easy solution that you can use with your Unicorn scripts as-is. Remember, “good enough” emulation is sometimes all that is needed to achieve impactful vulnerability discovery.

Cisco Talos Blog – Read More

When it comes to our children’s digital lives, prohibition rarely works. It’s our responsibility to help them build a healthy relationship with tech.

WeLiveSecurity – Read More

Easily secure access to your SaaS applications

Categories: Products & Services, Workspace

Sophos Blogs – Read More