Fortune 500 Tech Enterprise Speeds up Triage and Response with ANY.RUN’s Solutions

In enterprise SaaS, unclear security decisions carry real cost. False positives disrupt customers, while missed threats expose the business.

A Fortune 500 cloud provider addressed this risk by embedding ANY.RUN into SOC investigations, giving analysts the behavioral evidence needed to reduce escalations, improve triage confidence, and make proportionate response decisions at scale.

Company Context and Security Scope

The organization is a Fortune 500 enterprise SaaS provider headquartered in North America, supporting enterprise customers across multiple regions and regulatory environments, with a workforce in the tens of thousands.

- Industry: Enterprise cloud software and SaaS, where customers expect strong security, high availability, and strict data protection.

- Environment: Not endpoint-centric; security coverage spans a large multi-tenant SaaS platform, internal corporate environments, and a broad ecosystem of integrations, partners, and third-party access, each introducing distinct threat characteristics

- Security organization: A mature, multi-tier structure with dedicated SOC, incident response, threat hunting, and security engineering functions operating across regions.

Core Challenges: Volume, Ambiguity, and Escalation Friction

When we spoke with the security engineer, we expected the usual story, missing visibility, gaps in tooling, not enough telemetry. But the discussion quickly showed the real problem was somewhere else.

The issue wasn’t seeing what was happening. The team already had plenty of signals coming in every day: authentication events, API activity, admin actions, and a constant flow of partner and integration traffic. The issue was that most of it was legitimate, which made the dangerous moments harder to prove early.

On the surface, nothing looked wrong. But unclear alerts were consuming more and more of our time. We were drowning in uncertainty. For a company serving global customers, that level of ambiguity wasn’t acceptable.

During our discussion, it became clear that the pressure point was volume + ambiguity.

Key challenges:

Key challenges:- Too many alerts that were suspicious, but not provably malicious

- Tier-1 escalations driven by incomplete signals

- Tier-2 time lost on validation and confirmation work

- Uneven triage speed across regions and shifts

- Extra rework from low-confidence early decisions

- Constant need to balance customer impact vs. security risk

Defining the Right Direction for Triage and Response

Once we clarified the challenges, the priority became clear: make early triage decisions more certain, without increasing operational risk in a multi-tenant SaaS environment.

The team focused on:

- Reducing uncertainty during triage

- Improving confidence in early-stage decisions

- Separating isolated external issues from broader attack patterns and benign platform behavior

- Supporting proportional response, not aggressive automation

Solution: Behavior-Based Evidence in Early Investigations

To reach the clarity they were aiming for, the team needed a way to introduce reliable behavioral evidence into early-stage investigations, without disrupting existing SOC workflows or forcing premature automation.

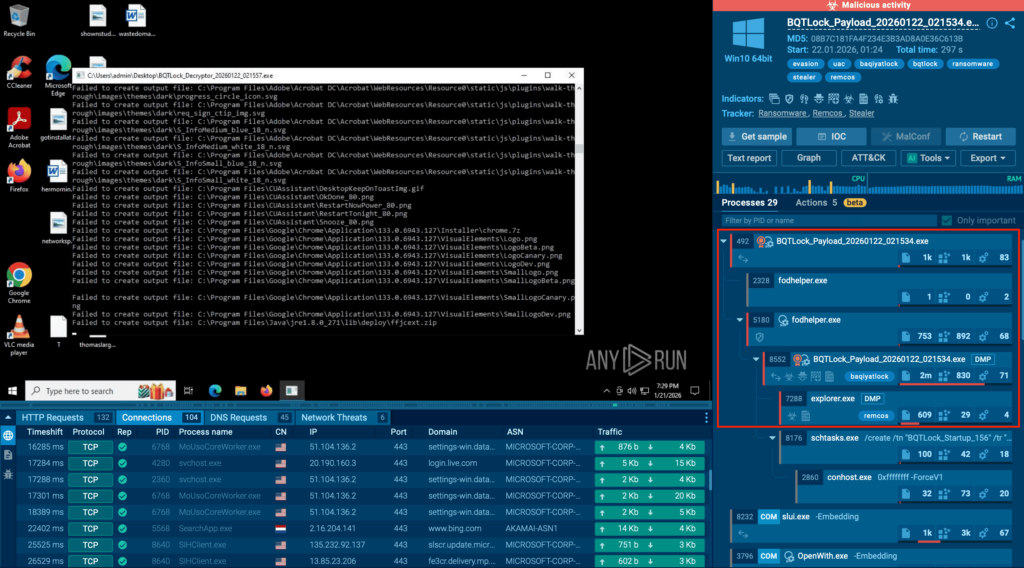

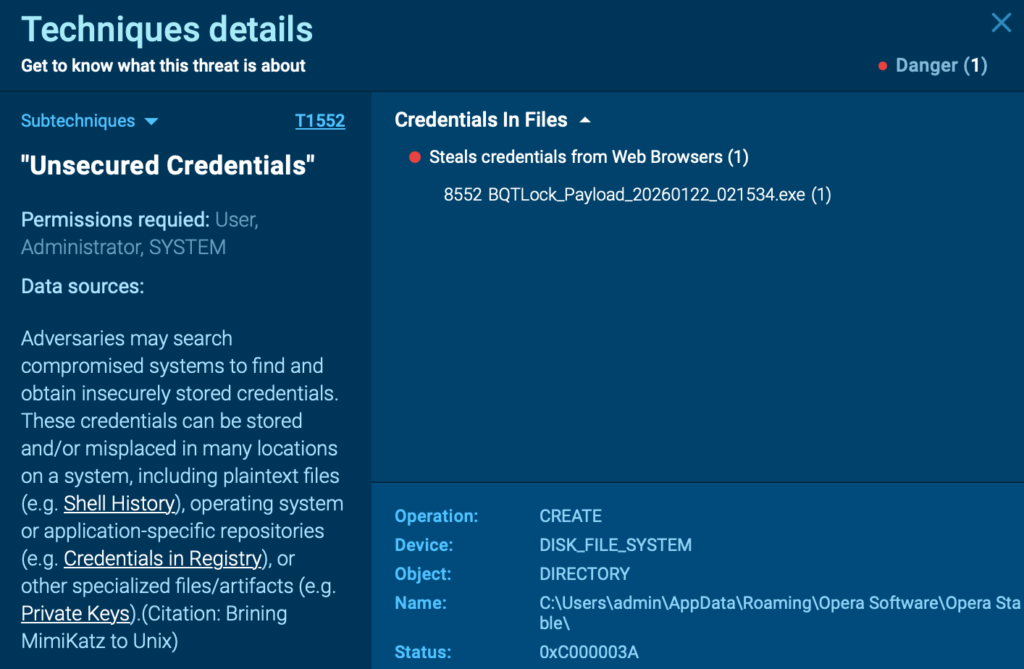

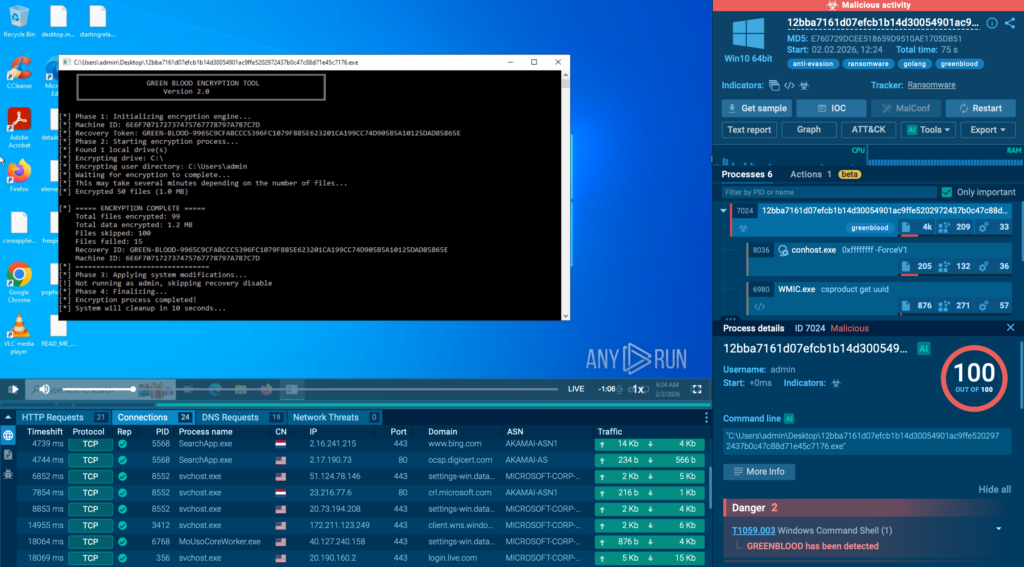

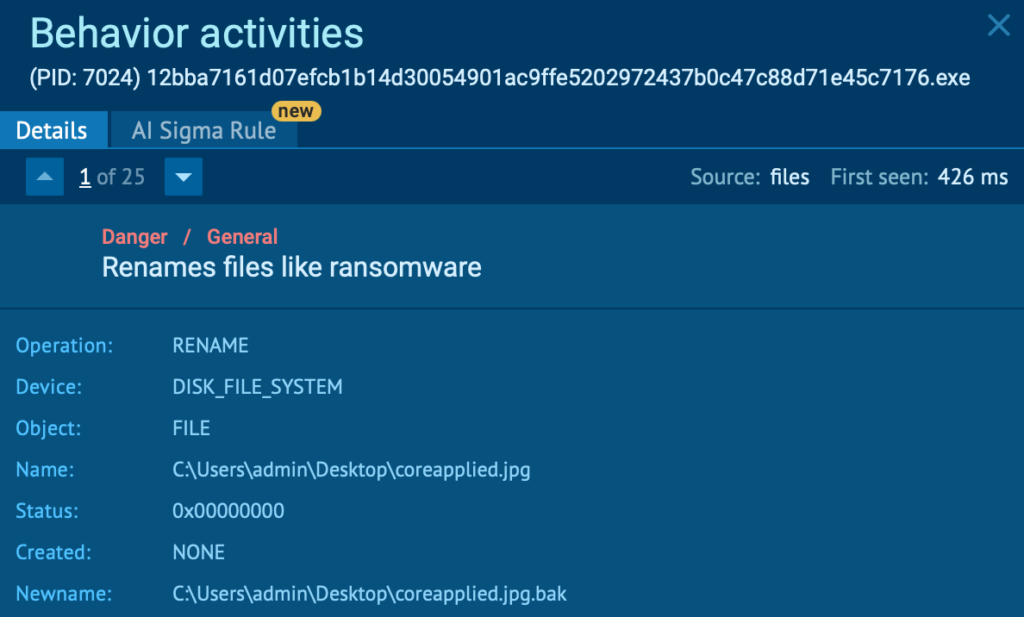

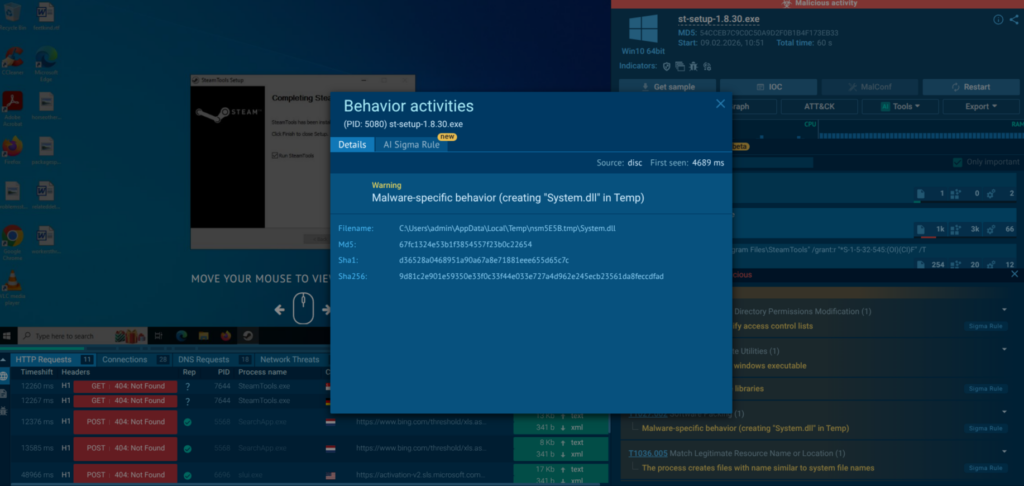

ANY.RUN closed this gap by giving analysts a safe way to observe the real behavior behind a suspicious file or link, replacing guesswork based on reputation, static indicators, or incomplete external signals with direct, controlled evidence.

The biggest change was moving from ‘this looks suspicious’ to ‘this is what it actually does.’ That kind of controlled, repeatable proof is what makes confident decisions possible, especially when threats originate outside your perimeter.

Rather than accelerating response blindly, this approach helped the SOC make earlier, calmer, and more proportional decisions within the same operational model.

Process Impact: Phishing and External Threat Triage

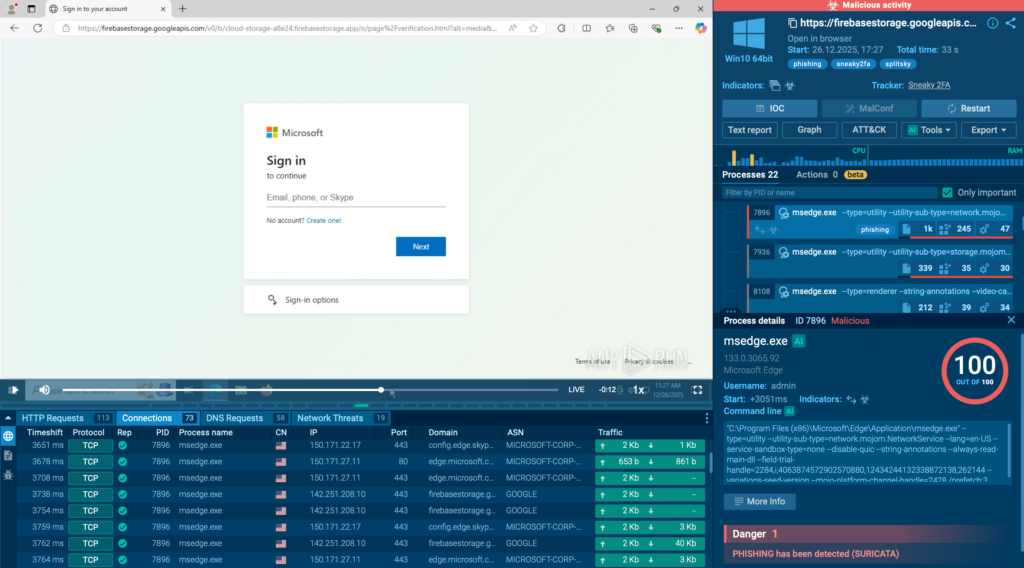

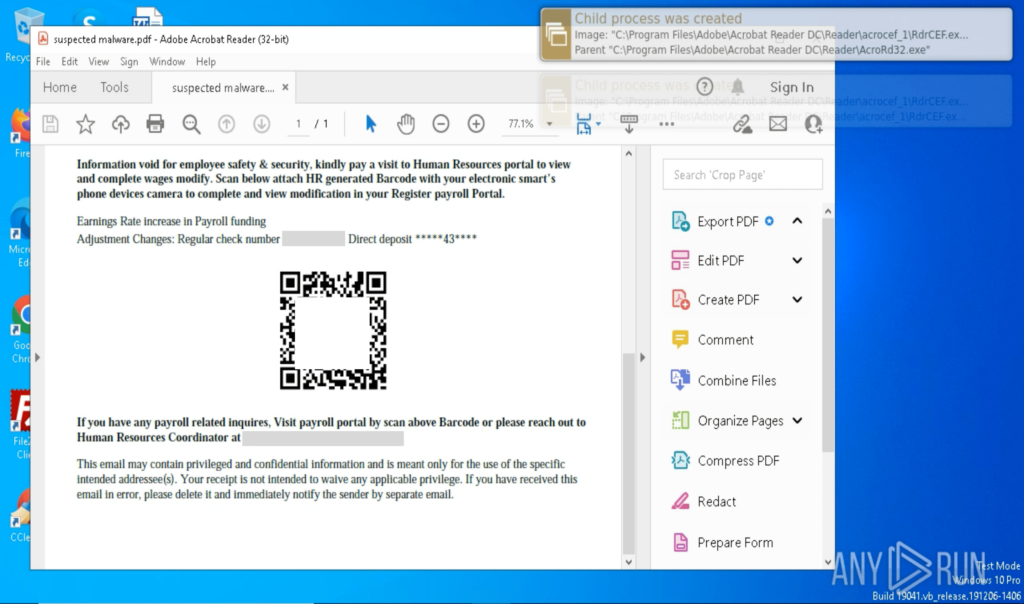

Phishing was one of the clearest use cases for the new approach. Many alerts weren’t obviously malicious, but they couldn’t be ignored either, especially when they involved links, attachments, or multi-step redirected flows coming from outside the company’s perimeter.

With behavior-based validation provided by ANY.RUN sandbox, Tier-1 no longer had to rely on “looks suspicious” signals to make the first call. Analysts could safely interact with artifacts, observe what actually happened, and capture the full chain; redirects, credential capture, payload delivery, or follow-on behavior.

In practice, this made a visible difference: in roughly 90% of cases, analysts were able to surface the full attack chain within about 60 seconds, turning unclear alerts into evidence-backed decisions early in the workflow.

A big part of the improvement came also from automated interactivity. Instead of spending time manually clicking through steps that attackers use to slow investigations, CAPTCHAs, multi-hop redirects, or links hidden behind QR codes, analysts could let the sandbox mimic user behavior and capture the full sequence safely. That meant faster verdicts, less friction, and more confidence at Tier-1 without relying on guesswork.

These shifts improved day-to-day operations:

- More cases closed confidently at Tier-1 when behavior was clearly benign or clearly malicious

- Escalations became more intentional, with evidence attached instead of uncertainty

- Tier-2 spent less time on basic confirmation and more time on true incident work

- Triage became more consistent across regions and shifts

Expanding Context with Threat Intelligence

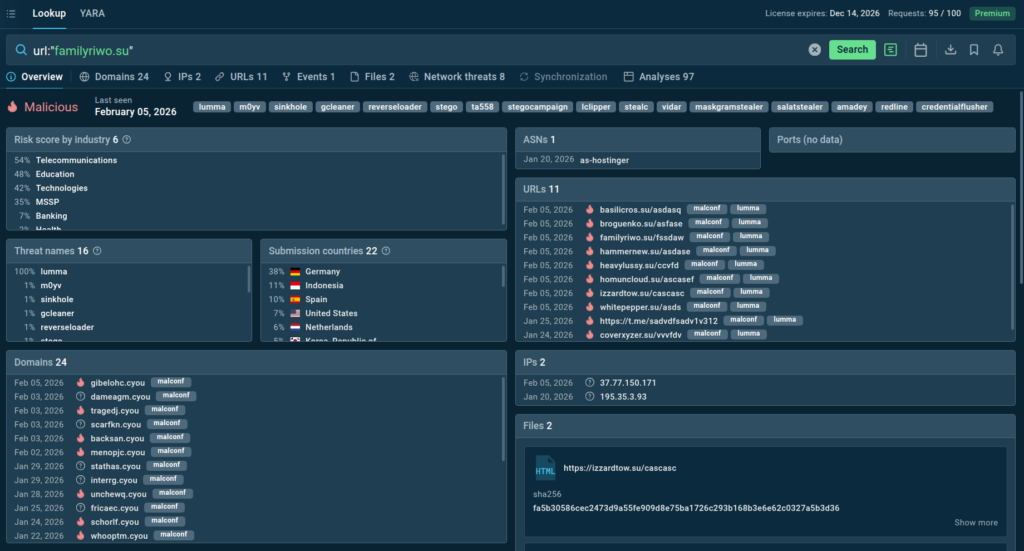

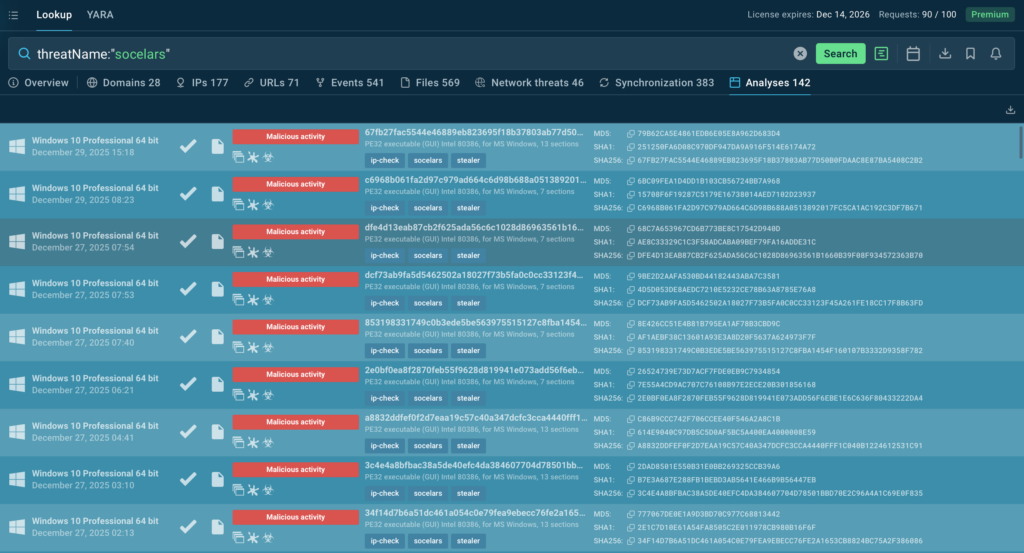

While behavioral evidence clarified what a threat does, the team also needed faster answers to what it means in the broader landscape.

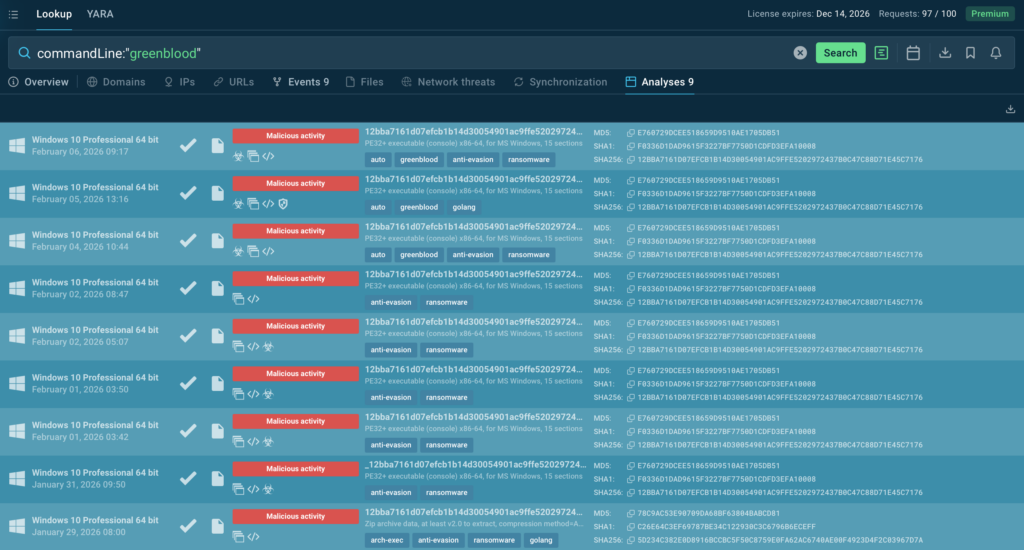

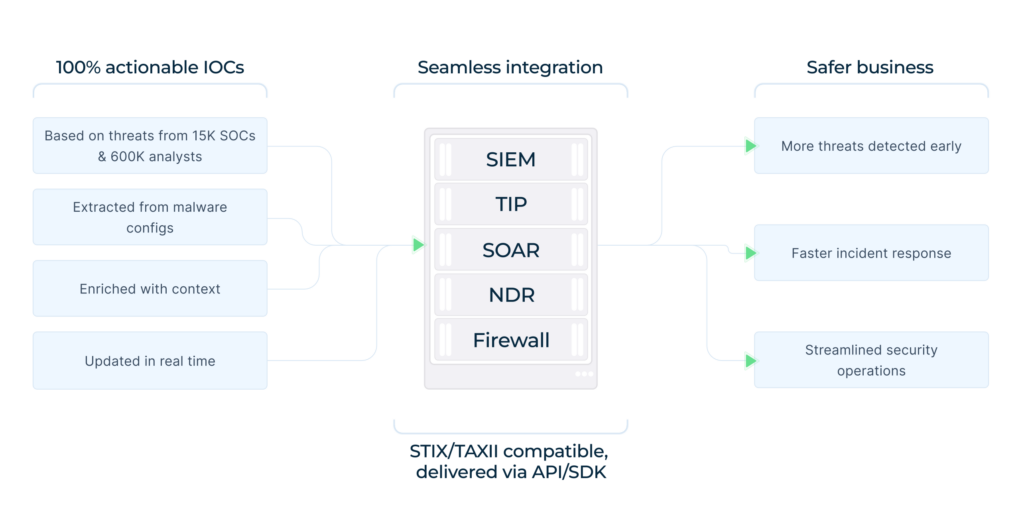

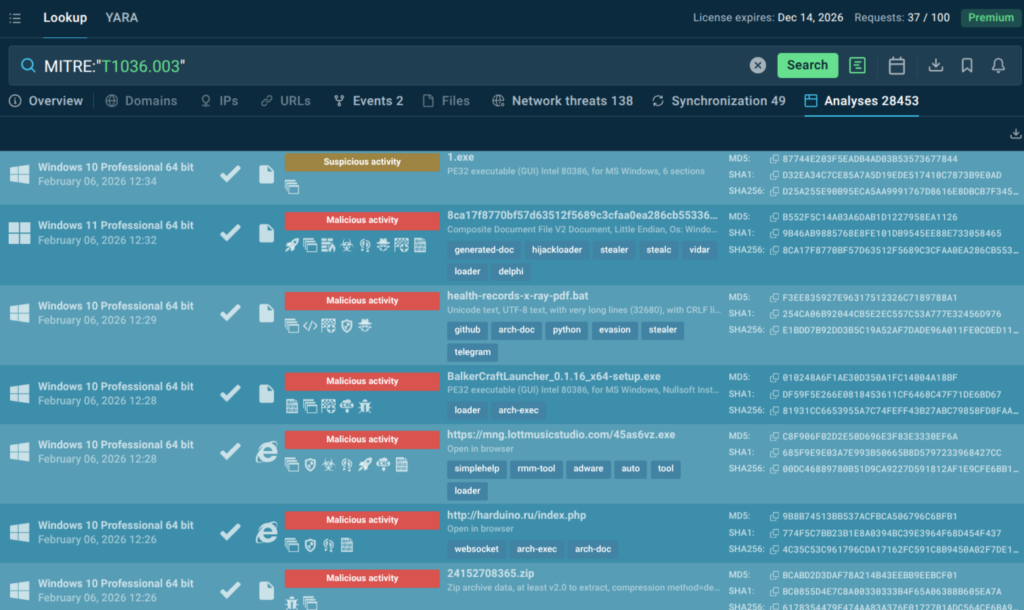

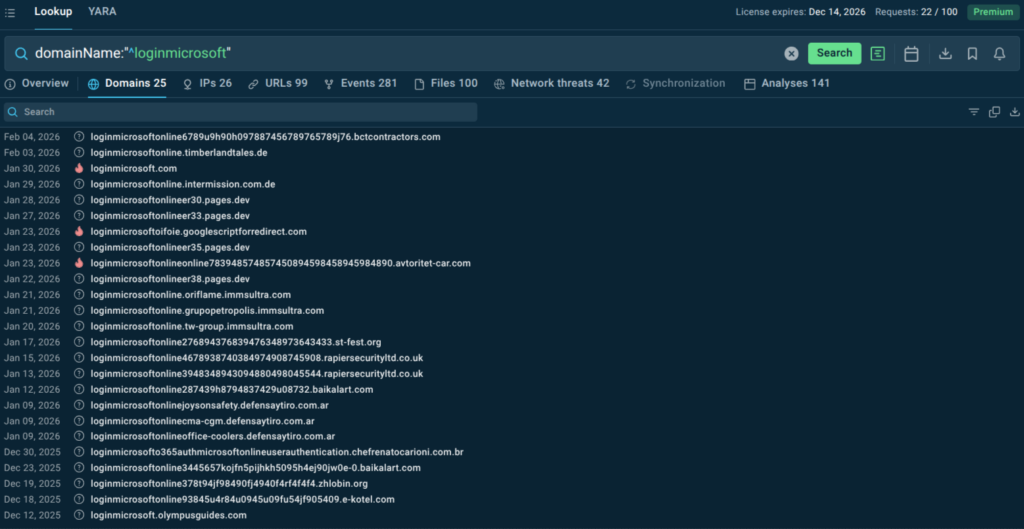

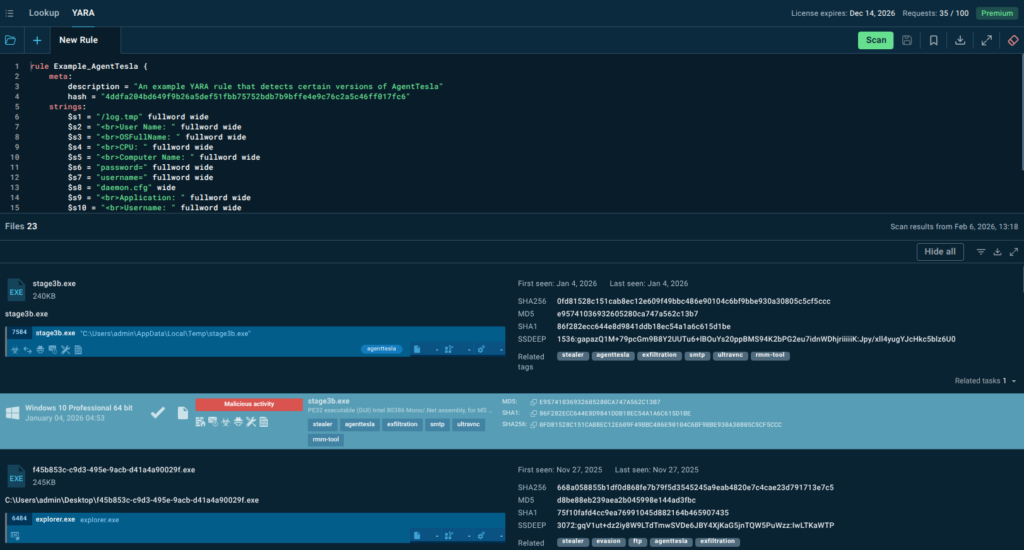

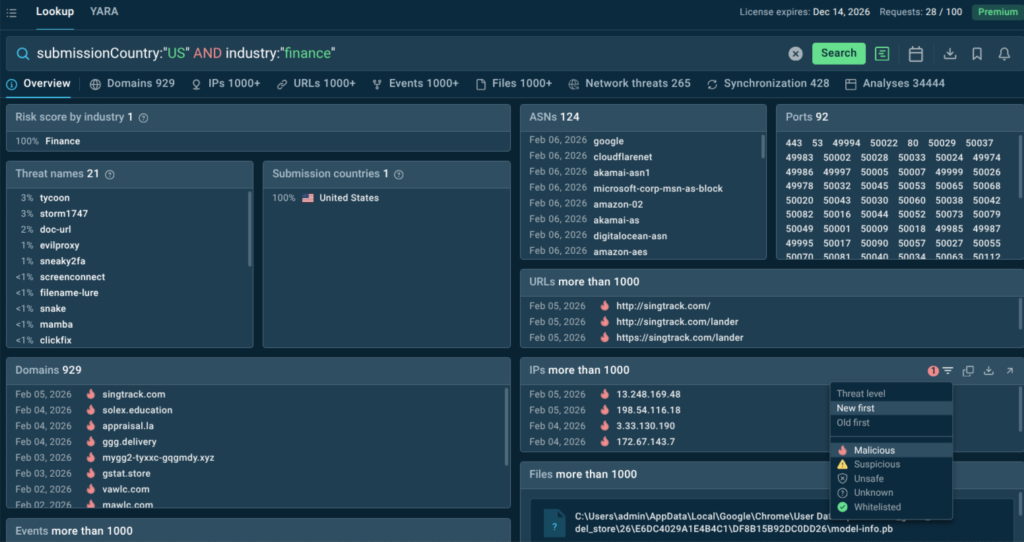

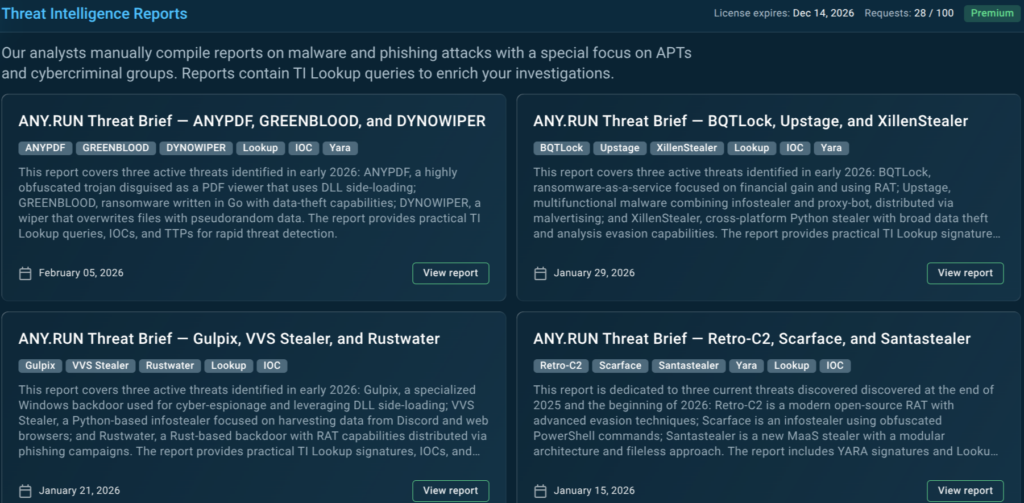

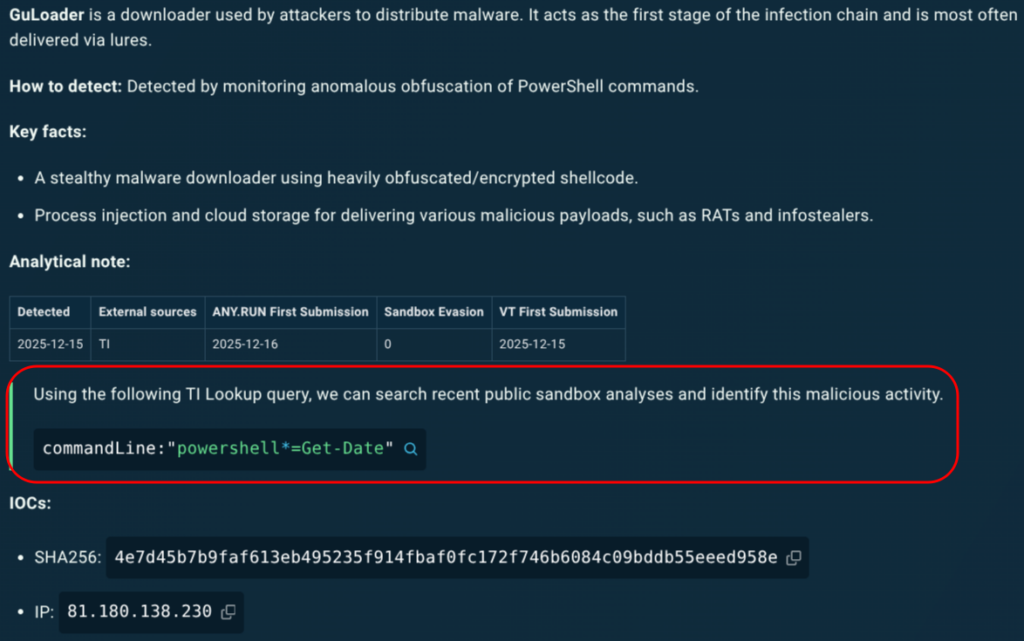

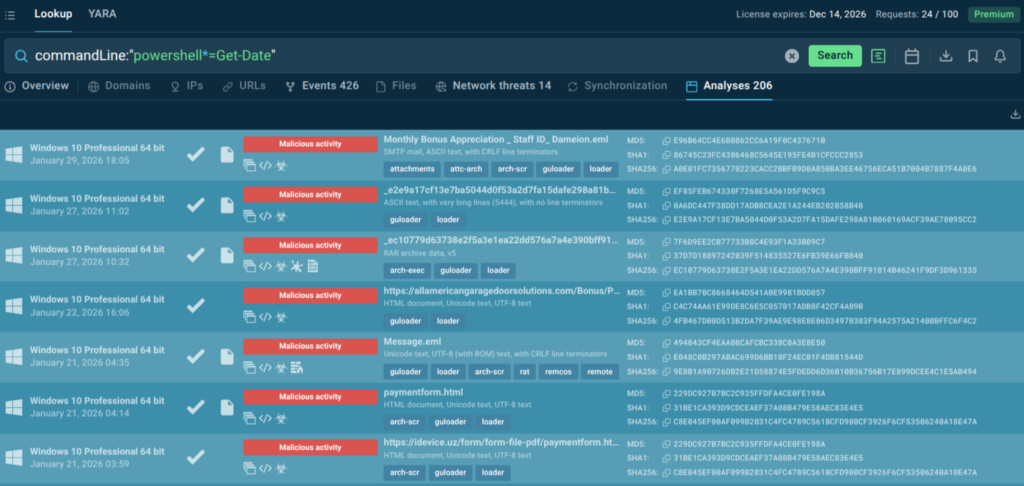

To close that gap, they decided to extend their workflow with ANY.RUN’s Threat Intelligence capabilities, adding immediate context to artifacts discovered during triage.

Threat Intelligence Lookup helped analysts quickly determine:

- Whether infrastructure was linked to known campaigns

- If observed behavior matched publicly reported threats

- How relevant an external signal was to their specific environment

We notice how our threat hunting is getting more grounded and faster to validate. When a hunt intersects with external artifacts, phishing payloads, suspicious links, or malware samples, we can confirm the behavior and enrich the hypothesis quickly, instead of spending time on patterns that stay theoretical.

At the same time, Threat Intelligence Feeds delivered behavior-verified indicators that could be correlated inside existing detection and monitoring pipelines, strengthening visibility without adding noise.

Together, these solutions allowed the SOC to move from isolated alert handling toward context-aware investigation, where decisions were supported not only by observed behavior, but also by real-world threat activity.

We started using TI Feeds as an enrichment layer on top of our existing threat intelligence stack. What stood out for us is that the indicators are tied to sandbox-verified behavior, so we’re not reacting to blind IOCs, we’re adding context we can actually trust.

As a result, analysts spent less time searching for background information and more time responding with clarity and confidence.

Measurable Improvements Across SOC Operations

As the new workflow stabilized, the team began to see consistent improvements across investigation quality, escalation patterns, and overall SOC efficiency:

Tangible Gains Across SOC

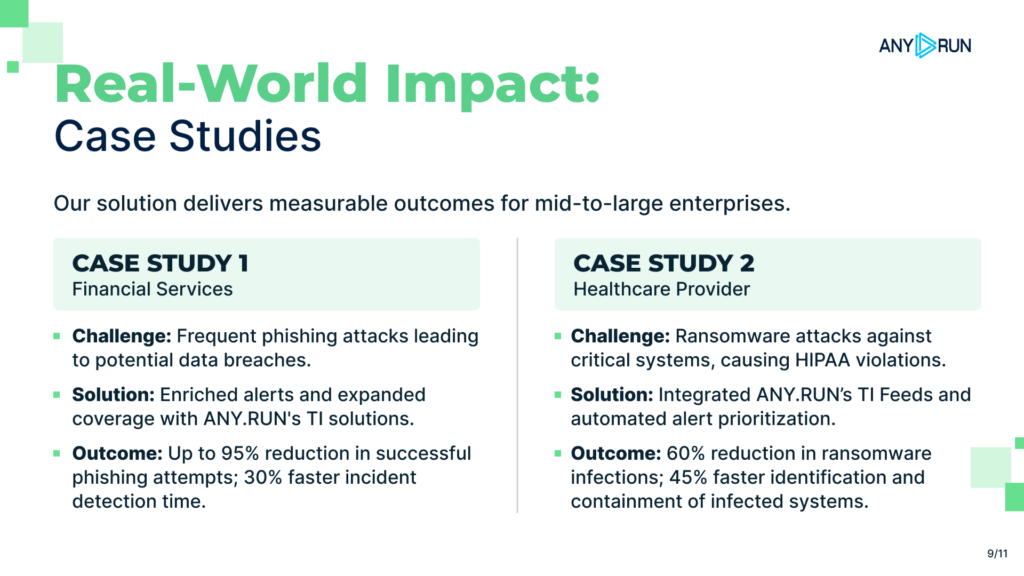

Tangible Gains Across SOC- Fewer unnecessary Tier-2 escalations decreased approximately 35%, driven by stronger early-stage evidence

- Average triage time per suspicious file or link dropped by 40% across regions and analyst shifts

- Higher-quality incident response handoffs, supported by behavioral proof and threat context

- Over 82% of ambiguous alerts were resolved without secondary review, allowing senior responders to focus on confirmed incidents

- Overall MTTR improvement by 24%, achieved through faster scoping and clearer decisions

What SOC Managers Reported After the Workflow Shift

Beyond individual investigations, SOC managers began to notice improvements in how decisions were communicated, reviewed, and justified across the organization.

With clearer behavioral evidence and immediate threat context, plus auto-generated investigation reports and built-in collaboration capabilities, updates to stakeholders became more straightforward, and post-incident analysis required far less backtracking.

Cases were easier to standardize across regions and shifts because the same evidence, context, and artifacts were captured and shared in a consistent way. Escalations increasingly arrived with supporting proof rather than open questions, which reduced “back-and-forth” and helped keep response actions proportional to real risk.

From a manager’s perspective, the biggest change was consistency. Decisions were easier to stand behind because the evidence and reporting were already there, and teams could collaborate on the same case without losing context.

Importantly, this progress didn’t require changing the overall security strategy. Instead, it reduced friction inside an already mature SOC model, helping ensure that when action was taken, it was taken for the right reasons.

Conclusion: From Uncertainty to Confident, Proportional Response

By embedding ANY.RUN into daily SOC operations, this Fortune 500 SaaS provider reduced ambiguity in early triage and strengthened decision-making across the entire workflow.

We just stopped losing time to uncertainty. Now we can confirm what’s happening faster and escalate only when it actually makes sense.

With behavioral evidence, immediate threat context, and consistent reporting built into investigations, the SOC became more predictable, more efficient, and better aligned with the need for proportional response at enterprise scale.

About ANY.RUN

ANY.RUN is part of modern SOC workflows, integrating into existing processes and strengthening the full operational cycle across Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3.

It supports every stage of investigation; from exposing real behavior through safe detonation, to enriching findings with broader threat context, to delivering continuous intelligence that helps teams move faster and make confident decisions.

Today, more than 600,000 security professionals and 15,000 organizations rely on ANY.RUN to accelerate triage, reduce unnecessary escalations, and stay ahead of evolving phishing and malware campaigns.

Check how ANY.RUN can improve investigation clarity and speed in your SOC

Frequently Asked Questions

Behavioral analysis allows analysts to observe what a suspicious file or link actually does in a controlled environment. This removes guesswork, enables earlier confident decisions at Tier-1, and reduces unnecessary escalations.

Yes. ANY.RUN is designed to fit into mature SOC environments without requiring workflow redesign, supporting investigation, enrichment, and reporting across Tier-1, Tier-2, and Tier-3 operations.

In many real investigations, the full attack chain can be exposed within seconds through automated interactivity and behavioral observation, allowing faster evidence-based classification.

Security teams across enterprises, MSSPs, and SOC organizations worldwide rely on ANY.RUN to accelerate triage, improve investigation clarity, and support proportional response to modern threats.

The post Fortune 500 Tech Enterprise Speeds up Triage and Response with ANY.RUN’s Solutions appeared first on ANY.RUN’s Cybersecurity Blog.

ANY.RUN’s Cybersecurity Blog – Read More